On the first of February, the military of Myanmar, also known as Burma, staged a coup to overthrow the democratically elected government of Aung San Suu Kyi. The armed forces had backed opposition candidates in the recent election, which Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy party won in a landslide. Since the coup, Suu Kyi has been arbitrarily detained, supposedly for possessing illegal walkie-talkies and violating a Natural Disaster law. Suu Kyi was previously detained for almost fifteen years between 1989 and 2010, although she continued to organize pro-democracy rallies while under house arrest. The military has stated that they are acting on the will of the people to form a “true and disciplined democracy” and that they will soon hold a “free and fair” election, after a one-year state of emergency.

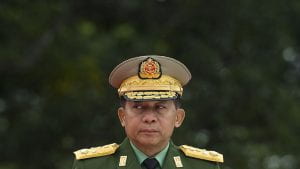

The military leader, Min Aung Hlaing, is currently in control of the country. Hlaing has been an influential presence in Myanmar politics since before the country transitioned to democracy and has long garnered international criticism for his alleged role in military attacks on ethnic minorities. There is significant cause for concern that a government under Hlaing will impose repressive anti-democratic laws, and more Islamophobic and ultra-nationalist policies.

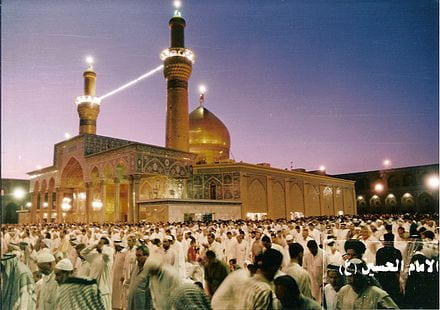

Since the 1970s, Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar have suffered from large-scale and orchestrated persecution. Myanmar’s official position, including under the Suu Kyi administration, has been that Rohingyas are illegal immigrants and thus are denied citizenship. In 2016, the military, along with police in the Rakhine State in northwest Myanmar, violently cracked down on Rohingyas living in the region. For these actions, the Burmese military has been accused of ethnic cleansing and genocide by United Nations agencies, the International Criminal Court, and others. The United Nations has presented evidence of major human rights violations and crimes against humanity, including extrajudicial killings and summary executions; mass rape; deportations; the burning of Rohingya villages, businesses, and schools; and infanticide. A study in 2018 estimated that between twenty-four and thirty-six thousand Rohingyas were killed, eighteen-thousand women and girls were sexually assaulted, and over one-hundred-sixteen thousand were injured (Habib, Jubb, Salahuddin,Rahman, & Pallard, 2018). The violence and deportations caused an international refugee crisis which was the largest in Asia since the Vietnam War. The majority of refugees fled to neighboring Bangladesh, where the Kutupalong refugee camp in Ukhia became the largest of its kind.

Aung San Suu Kyi has not been immune to criticism for her inaction during the genocide, with many questioning her silence while the military carried out gruesome crimes. Suu Kyi also appeared before the International Criminal Court of Justice in 2019 to defend the Myanmar military against charges of genocide. Regardless, she is a Nobel Peace Prize laureate who enjoys broad support from the people of Myanmar, and there seems to be very little legitimate justification for her removal from power. Protests in response to the coup have grown rapidly since early February, with the BBC calling them the largest in Myanmar since the 2007 Saffron Revolution.

The United Nations Human Rights Council met in special session in mid-February to discuss the coup, recommending targeted sanctions against the leaders. Deputy UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Nada al-Nashif and Special Rapporteur Tom Andrews argued that action taken against the coup’s orchestrators would not hurt Myanmar’s already vulnerable population. They urged the United Nations to take action to replace Min Aung Hlaing and the rest of the military leadership in a broad restructuring that

would put the military under civilian control. There is an increasing sense of urgency from human rights bodies due to troubling information getting out of the country, despite repression of the media by the military junta. Reports have started to come to light of live ammunition and lethal force being used against protestors and several protestors have been killed. In addition, over two-hundred government officials from Suu Kyi’s administration have been detained, with many being “disappeared” by plain-clothes police in the middle of the night. The UN has long been critical of the Myanmar military, with Deputy UN High Commissioner for Human Rights Nada al-Nashif recalling the Human Rights Council’s 2018 report which stated that the “[military] is the greatest impediment to Myanmar’s development as a modern democratic nation.” The Burmese military has functioned for over twenty years with impunity, benefiting from virtually non-existent civilian oversight and disproportionate influence over the nation’s political and economic institutions.

On February 27, the military removed the nation’s UN Ambassador from his position.

Ambassador Kyaw Moe Tun had on the 26th denounced the coup as “not acceptable in this modern world” and asked for international intervention by “any means necessary” to end military control. Special Rapporteur on Myanmar Tom Andrews called Moe Tun’s speech a “remarkable act of courage”. Ambassador Moe Tun’s unexpected speech reinvigorated the protestors on the ground, who have faced steadily more intense crackdowns from the government forces. “When we heard this, everyone was very happy, everyone saying that tonight we are going to sleep very happily and encouraged,” Kyaw Win, executive director of Burma Human Rights Network said, “These are peaceful protesters, civilians. And they are standing up against a ruthless, brutal army. So you can see that without any international intervention or protection, this uprising is going to end very badly.”

International response to the coup has been varied. UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres called it a “serious blow to democratic reforms”, while the United States and United Kingdom have sanctioned military officials. US Secretary of State Blinken issued a statement saying “the United States will continue to take firm action against those who perpetrate violence against the people of Burma as they demand the restoration of their democratically elected government.” On the other hand, China blocked a UN Security Council memorandum criticizing the coup, and asked that the parties involved “resolve [their] differences”, while Myanmar’s neighbors Cambodia, Thailand, and the Philippines have characterized the coup as an “internal matter”.

Additional References:

Habib, Mohshin; Jubb, Christine; Ahmad, Salahuddin; Rahman, Masudur; Pallard, Henri. 2018. Forced migration of Rohingya: the untold experience. Ontario International Development Agency, Canada. ISBN 9780986681516.