By James DeLano

“I don’t feel safe here.”

That statement was uttered repeatedly in interviews performed by the Alabama Disabilities Advocacy Program (ADAP) with residents of Sequel Courtland, a psychiatric group home for boys in Courtland, AL. The residents of the home reported consistent patterns of abuse. One boy “reported witnessing a staff member lifting another resident up by the throat and slamming him to the floor.” Multiple boys reported being slammed into the ground and not being allowed to receive medical attention.

Sequel Courtland is a facility for boys. At the time the letter was sent in July 2020, there were “at least two transgender girls inappropriately placed at Courtland,” one of whom reported that she “is constantly touched, smacked on the butt” and that “they [other residents] try to watch me dress.”

At a Sequel facility in Owens Cross Roads that was part of the same investigation, “male staff repeatedly enter girls’ bedrooms and put them in violent containments.” At the same facility, residents were frequently ordered to sleep in common areas rather than in their bedrooms as a punishment. Staff also failed to report or make any attempt to prevent suicide attempts.

Sequel Montgomery practiced “Group Ignorance” as a punishment. Group Ignorance, or GI, involved staff and other residents completely ignoring the person being punished. The isolated person was unable to interact with peers in any way; just being within ten feet of another resident would be considered a violation. The facility’s then-current guidelines read that “They can participate with peers only during direct billable services—BLS and therapist-led group therapy.” One resident reported attempting suicide specifically because of the stress of being isolated under GI.

Sequel Tuskegee utilized a “time-out room” for up to days at a time as a means of controlling residents. There was no mattress present in the room; boys were required to move the mat from their bedroom into the confinement area. It also lacked a toilet or sink. Because of that, residents were forced to either try – and often fail – to gain staff’s attention to use the restroom or, failing that, “urinate in the corner of the room and clean it up later.”

A Sequel group home in Ohio was also investigated by that state’s protection & advocacy (P&A) agency, Disability Rights Ohio. They reported that one of the children living at that home told them he was “Put in a hold so strong that it almost broke my arm; they kept holding me tighter and tighter; my hands and arms were tingling and going numb.” Another said, “I don’t feel safe.”

Abusive group homes are not exclusive to Sequel. Group homes are often abusive, no matter what company owns them.

At a residential facility called Canyon Hills Treatment Facility in North Carolina, “at least one-third of residents lost weight after they were admitted for treatment.” Canyon Hills’ residents were children who should still have been growing. When residents asked for more food, their portions were cut even further. At another facility in North Carolina called Anderson Health Services, “Ten staffers at this facility have been charged with child abuse since 2017.”

At a group home in California, a woman with severe autism often went out on rides in the home’s van. She occasionally tried to stand up, after which “the staff member driving would slam on the brakes and, like, brake check her.” That practice caused bruises. The same woman, who had harmed herself in the past, was frequently left alone and unsupervised, during which time she banged her head into the wall, leaving large holes in the process.

Neglect in Group Homes

Many group homes are chronically understaffed. That, along with low pay and a lack of care from and proper training for staff, collectively leads to preventable injuries and death.

A woman choked to death at a New Jersey group home in 2017. She was unable to swallow large pieces of food; everything needed to be in small pieces, and she required supervision while eating. Two years prior, she had been taken to the hospital after choking on a bagel – an incident her family was never told about.

As a result of poor staffing, a resident of an Oklahoma group home named Terry Brown was strangled by his roommate. There was only one staff member on duty; when she intervened, she was attacked as well and “watched Terry’s body turn purple, go limp and fall lifeless.” At a group home owned by the same company, a resident drowned in 2011 on an outing. He was supposed to be wearing a life jacket. When he died, there was no life jacket for him to wear.

One Texas caregiver worked for almost 70 hours straight while caring for two disabled women; her only breaks were a short nap and a trip to run errands. She is the only caregiver for two women who require constant care and supervision. She was clocked in from 8:16 Tuesday morning to 10:08 Friday morning, and only four hours after clocking out she returned for another 19-hour shift. She said that, “I’m always here. The only thing I do for fun — besides sleep — is go to church, read my Bible, hang out with my family.” The only occasional help she has comes from equally understaffed and exhausted workers at other group homes. For her work – providing constant, necessary care to two people – she makes $9 per hour, which is a wage that is not uncommonly low and serves as one of many reasons group homes are so often neglectful.

At the previously mentioned Sequel group home in Courtland, Alabama, ADAP investigators found blood and feces on windows and floors. The same investigation had residents report insufficient and inadequate food and water, nonexistent education and medical treatment, and that “there’s mold in the showers, and rats and roaches in our bedrooms and the hallway.”

Physical and Chemical Restraint

Mental healthcare professionals generally agree that restraining someone who is in crisis only makes things worse. Many group homes do it anyway.

As part of the previously mentioned investigation into Sequel facilities in Alabama, numerous instances of inappropriate restraint were reported. A report compiling the results of several investigations by various state Protection & Advocacy Agencies (P&As) reads about an Alabama group home, “One boy described his head being caught on a nail in the wall during a restraint; another said he was picked up and slammed on his stomach onto the concrete. A boy who had visible gashes to his head said that facility staff had slammed him against a wall the previous night.”

In 2020, a 16-year-old boy was physically restrained by several staff members at a Sequel facility in Kalamazoo, Michigan, for twelve minutes. They used their body weight to restrain his torso and legs. He died two days later due to being asphyxiated while he was restrained. His name was Cornelius Frederick. In the 18 months preceding his death, emergency services visited the facility 237 times.

A group home in Carlton Palms, Florida has yet another pattern of restraints being used. Those restraints include cuffs, residents being strapped to chairs or being tied down, and straitjackets. These restraints directly cause physical harm – broken bones, bruises, and broken teeth, to name a few.

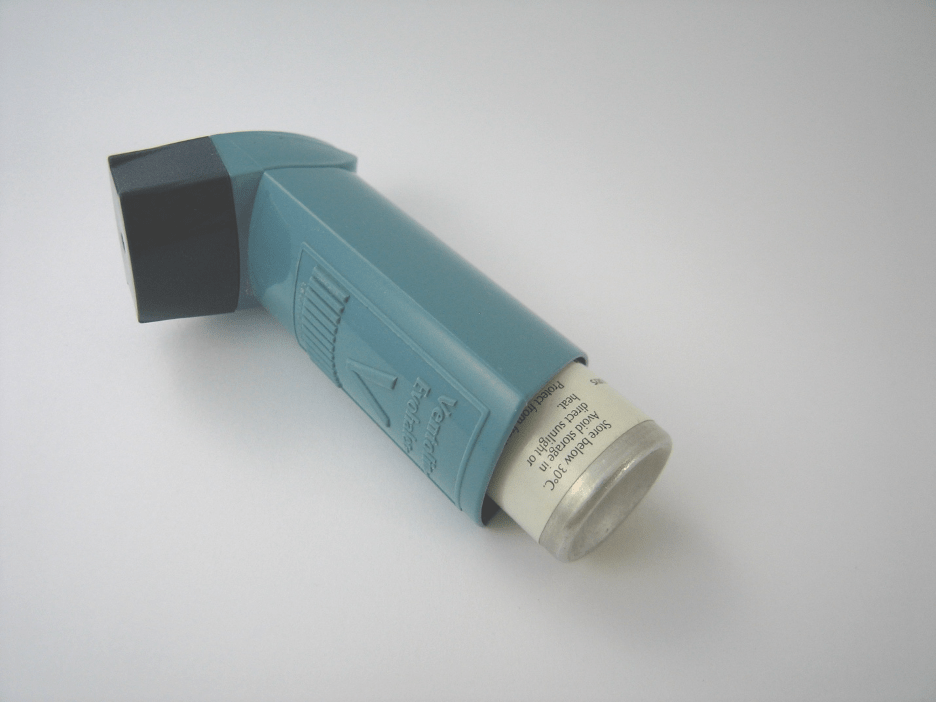

Seroquel is an antipsychotic drug that is approved by the FDA to treat some severe mental illnesses. Seroquel does not have an immediate effect. It is not approved as a form of chemical restraint or as a treatment for insomnia or anger management, among other off-label uses, but that is what it has been marketed and used for. Disability Rights Tennessee, the P&A agency in Tennessee, reported that “In one facility, staff increased a child’s Seroquel dosage from 50 mg to 300 mg as an emergency intervention.” The same problems occurred in North Carolina; “staff had administered Seroquel numerous times to a child who did not have any diagnoses that would indicate use of antipsychotics.”

What Is Being Done?

Several of the group homes mentioned above have shut down since investigations into them concluded, including some Sequel group homes. Sequel changed its homes’ names to Brighter Path due to the negative press. In other cases, states have stopped sending children to abusive group homes or, rarely, revoked their licenses. Other group homes, while not yet shut down, are no longer receiving new residents or are being downsized.