By Eva Pechtl

Samuel Walker proposes that America has two crime problems, one affecting most white, middle-class Americans and another affecting mostly people of color in poverty. Racial bias has been expressed in drug policy for centuries and has not ceased to marginalize certain racial and ethnic minorities. Chinese immigrants have been historically discriminated against in the United States and have not ceased to face racism in everyday life, especially after being associated with the COVID-19 pandemic. Bias has not only affected drug policy over time, but drug policy has reiterated this bias.

Stigma refers to a negative attitude toward a particular group of people, which is usually unfair and leads to discrimination. Stigma can be both explicitly expressed, like thinking people with mental health conditions are dangerous, and subtly embedded in societal norms, like repeatedly showing people of certain groups in the media in negative situations. Labeling someone in a positive or negative way is an easy solution to avoid the toll of understanding the challenges they are experiencing. Stigma is hugely based on social identity and perception of other groups, in that negatively stigmatizing other groups can be a way to justify inequalities in one’s own privilege compared to others.

Understanding stigma toward other social identities is especially important in the context of historical and present drug policy. In this series of blogs, I will explore some important historical examples of how stigma against minority groups has been embedded in American drug sentiment. Throughout this series, I will review the opium trade and Chinese repression, the criminalization of marijuana and Mexican immigrants, the unequal playing field of the hippie counterculture movement and the Indigenous Peyote movement, and the controversy over racial disparities in crack and cocaine sentencing. I hope to offer new perspectives on how targeting and incarcerating drug users has resulted in challenges specifically for minority groups, and how stigma hurts in the criminal justice system.

Outlining the Opium Wars in China

An early point to recognize in the development of drug prohibition was the Opium Wars in China and their effects on the criminalization of Chinese immigrants, especially in the US. This example importantly impacted policies on opiates, the term for the chemicals found naturally and refined into heroin, morphine, and codeine. These variations are derived and created from opium, a depressant drug from the sap of the opium poppy plant. Opioids can refer to both naturally derived opium and its variations synthetically made in the laboratory, like oxycodone and hydrocodone (partly synthetic) or tramadol and fentanyl (fully synthetic). As a medication, opium is meant to be used for pain control, but smoking opium causes euphoric effects almost immediately since the chemicals are instantly absorbed through the lungs and to the brain. The coming of opium smoking to the US created very toxic discrimination by those in privilege against Chinese immigrants, leading to blatant policies against Chinese people in poverty, even when the opium frenzy that followed was far from their goal.

In the 1700s, opium poppy fields in India were conquered by the British Empire and smuggled into China for profit. Even though China banned the opium trade in 1729, the illegal sale of the drug by outside nations caused an addiction epidemic and devastating economic consequences. In the Opium Wars, the Qing Dynasty attempted to fight against opium importation, but the British consistently gained more power over trafficking and forced China to make the opium trade legal by 1860. China had imported tea through the East India Company to Britain for many years, but it no longer appealed to Britain’s trade options, and this was detrimental to trade. As Britain ran out of silver to maintain the tea trade, the East India Company found that opium could be sourced in bulk from China, which led to a growing and promising market. The East India Company did not initially create the demand for opium but found a way to maximize the economic disruption and addiction in China for the benefit of trade.

Opium was then trafficked increasingly and was effectively destructive to the Chinese. For example, for the British to get their fix of caffeine, the Chinese got their fix of opium. The drug was sold and medicalized to merchants around the world, notably America, which played a significant role in finding new sources of supply from China and expanding the opium market until 1840. In Chinese culture, smoking opium was initially a ritual luxury that was used to display privilege, but as it became more accessible, the government was less concerned with controlling its pharmacological effects and more with controlling the social deviance associated with it. The Opium Wars ended in an unequal trading arrangement in Europe’s favor, continuing importation and causing the market to become socially segmented. Depending on their wealth, people bought different varieties of opium. However, addiction did not discriminate by wealth.

Judging Drugs by Culture

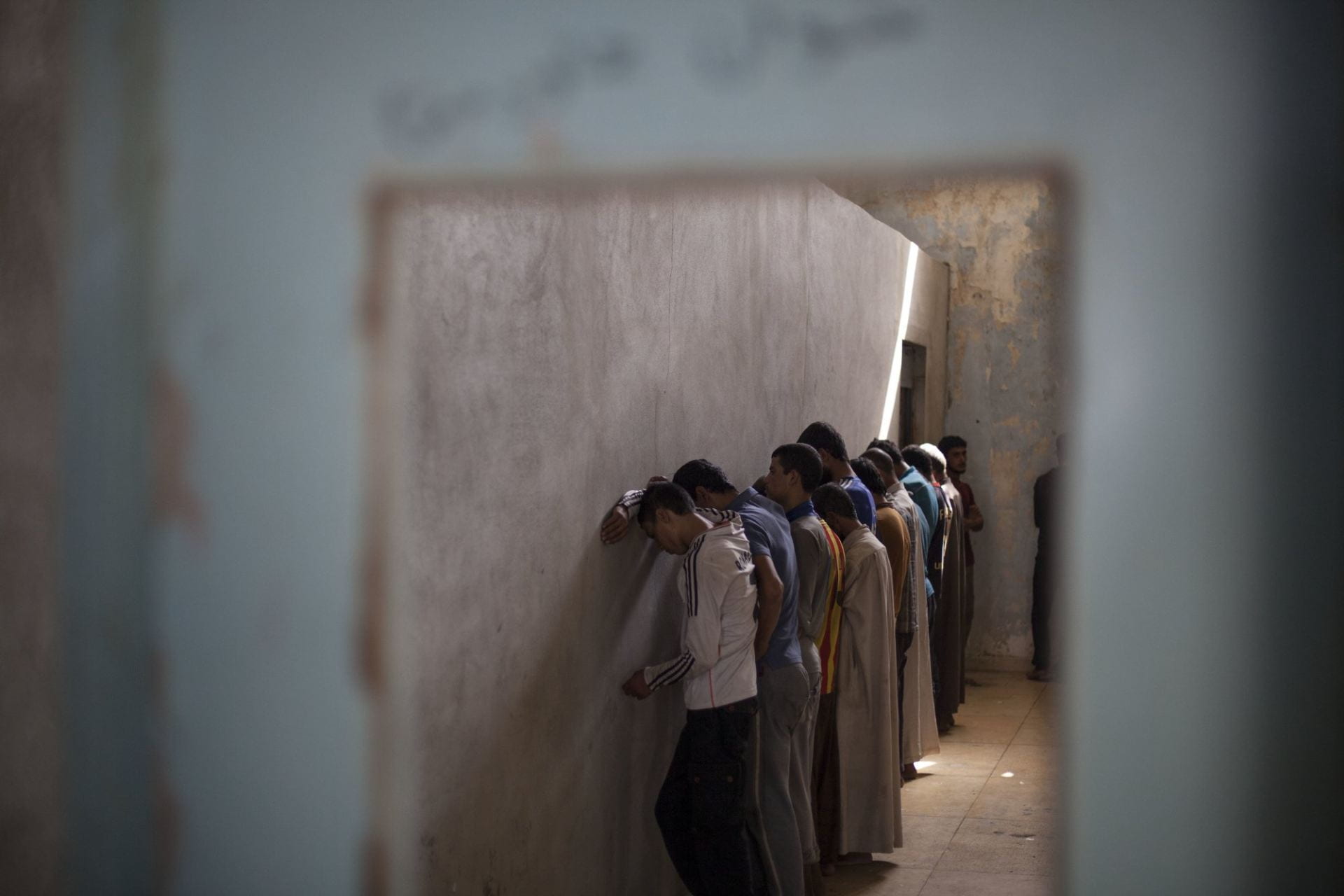

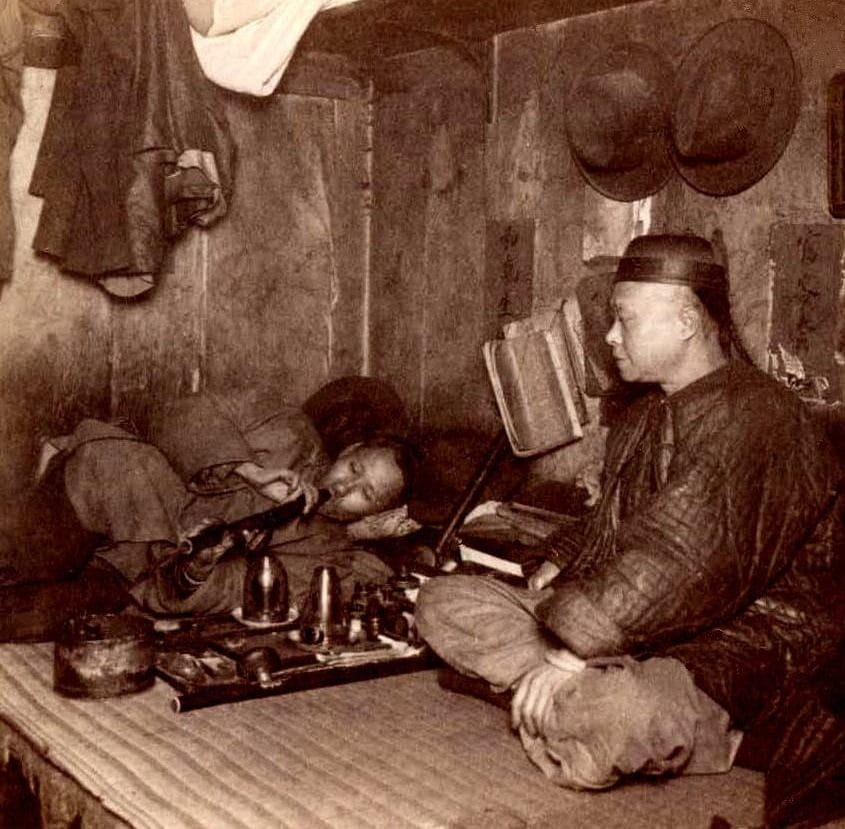

When many Chinese immigrants came to the US in the mid-1800s, primarily to escape the social and economic devastation brought upon them by the Opium Wars, they were an easy scapegoat for US politicians to blame for the internationally emerging opium crisis. Opium smoking, as well as poverty, was popular among them, so many started businesses of their own, including Opium Dens. These were hidden places to smoke without social consequences, popular in San Francisco, and were typically run by Chinese immigrants, though people of all backgrounds could be found there. These dens were compared to sin and hell, which only increased the already pervasive anti-Chinese sentiment. There was popularity in claims that vulnerable white women who entered the dens were manipulated and their honor surrendered by Chinese men. Males made up 95% of Chinese immigrants in the late 19th century, working for the few available jobs amid the great depression, leading to strong discriminatory sentiment among Americans affected by unemployment, such as referring to cheap laborers as ‘opium fiends.’

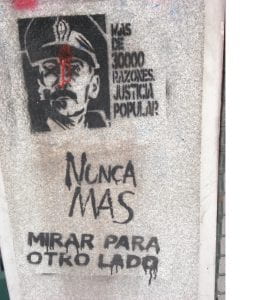

Chinese people were at first welcomed by some Americans as “the most industrious, quiet, patient people among us,” by a California newspaper in 1852. Still, tensions rose at the same time that immigrants started impacting opium use and the workforce. Policies on opium reflect xenophobia and racism, perpetuating fear of the ‘yellow peril,’ a racist color metaphor in American campaigns disguised as ‘anti-drug.’ To further conceptualize racism in politics during this time, the California Supreme Court case People v. Hall in 1854 categorized several racial and ethnic minorities as lacking the progress or development to testify against White people. Even if states did not blatantly pass these laws, Chinese people would be dismissed as liars before even speaking for themselves. This pervasiveness made it impossible for Chinese immigrants to seek justice against the severe discrimination and bias of the drug wars or practically any repressive measures they were subjected to. With the completion of the railroad in 1869, thousands of Chinese people were out of work, denied access to jobs, and targeted as competition as soon as they began to succeed.

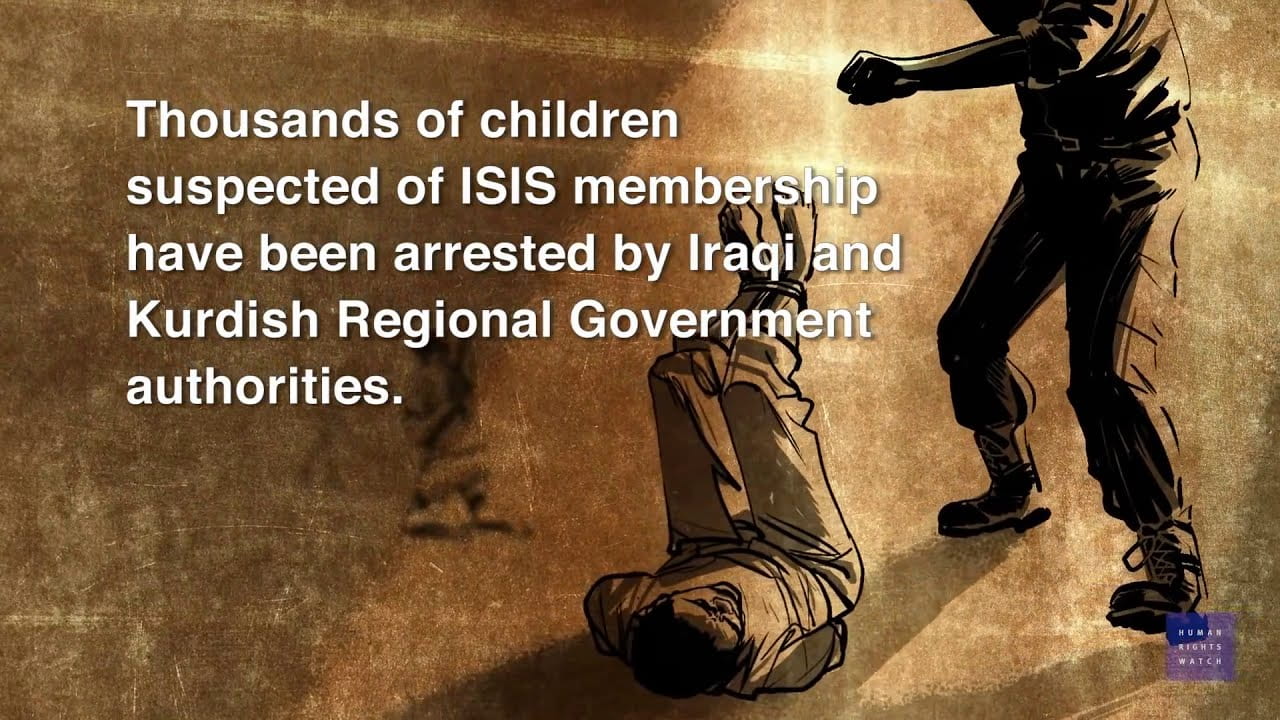

By the 1870s, it became apparent that many individuals, including white people, were picking up on opiate addiction. Opium use had increased alarmingly by the 1880s across the American medical field as well, and this led to criticism of Chinese immigrants by people who saw their fellow Americans as plagued by a disgusting habit. When more others were associated with Chinese people in this way, the criminalization of Chinese people represented a shift in focus toward protecting the perceived integrity of white people. For example, the San Francisco Opium Den Ordinance in 1875 made it illegal to maintain or visit places where opium was smoked, so many Chinese people and their neighborhoods were criminalized. Essentially, the US passed the Chinese Exclusion Act in 1882, which was the first major federal legislation to explicitly restrict immigration for a specific nationality. This meant pushing Chinese people away from the US even when they were producing the backbone of American railroad labor and only making up 0.002% of the population at that time.

Parallels of Criminalization and Overprescription

The Smoking Opium Exclusion Act in 1909 continued to ban the possession, use, and importation of opium for smoking, being the first federal law to ban the non-medical use of a substance. Even though opioids were rampantly prescribed and available in America by this time, the criminalization only applied to smoking opium, primarily done by Chinese immigrants in Chinatowns. Contrary to assumptions, it is not illegal drug cartels but pharmaceutical companies that fueled the opioid epidemic. For example, many Union soldiers in the Civil War returned home addicted to opium pills or needing treatment only possible by hypodermic syringes, which had become widely overused by both doctors and addicts due to their powerful relieving abilities. Male doctors prescribed morphine for women’s menstrual cramps, and it was even infused into syrup to soothe teething babies who became addicted. This was known as the ‘Poor Child’s Nurse,’ since the drug often led to infant death by starvation when sold as a medicine to calm hungry babies. In a broad sense, depending on or relating to one’s racial or ethnic community, opioids were regulated differently.

When narcotic sales were banned in 1923, this forced many addicts subjected to this overprescription to buy illegally from the thriving black markets, especially in Chinatowns, again criminalizing Chinese people. Countless doctors warned and panicked over the rising commonality of addictiveness in opiates as early as 1833, and opium was rapidly synthesized by scientists all over the world into more dangerous variations. When problems with addiction to medicalized opioid variations spun out of control, the US blamed Chinese immigrants rather than consulting with the professional field to avoid harm in the irresponsible dispersion of highly addictive drugs. Instead of dispersing research on the new and dangerous variations, opium smoking was specifically centralized, with opium being generalized into street names like ‘Chinese molasses’ or ‘Chinese tobacco.’

The narrative of opioid addicts was changed when opioid abuse rose among white people, and by this, I mean both the attitudes toward addiction and the actions taken to solve it. Framing addiction as a disease rather than a disgusting crime came when it was no longer just people of color getting in trouble. The idea of pharmaceutical treatments for drug abuse came when it was white people suffering and dying from the opioid epidemic. Meanwhile, opium ordinances had a heavy burden on the incarceration and continued detainment and deportation of Chinese people in the United States especially before accurate research was done. Repression was tied to opium but also purposely deprived Chinese immigrants of opportunities to succeed and created criminalized reputations among their communities. Despite its age, the history of the Opium Wars and its impact on societal discrimination in America is not a point to be missed when considering drug stigmatization.