Since 2014 and the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecurity has been steadily rising, with hundreds of millions being threatened by malnutrition and hunger. In 2020, above 30% of the global population was found to be moderately or severely food insecure. Food insecurity affects different populations in distinct ways, and in order to understand this more clearly, we examine Ecuador. Here, historical contexts have unique influences on food insecurity, but also, this nation exemplifies the reality that low-income nations face when combatting hunger.

Facts and figures of food insecurity in Ecuador

Hunger is an issue that is widespread globally and within Latin America and the Caribbean. In fact, researchers Akram Hernández-Vásquez, Fabriccio J. Visconti-Lopez, and Rodrigo Vargas-Fernández found that the region has the second-highest figures for food insecurity globally. The region is also predicted to be the fastest-growing in food insecurity rates.

Ecuador is just one example of why food insecurity manifests and in which populations. The country is ranked second in the region for chronic child malnutrition: 23% of children under five and 27% of children lack access to proper nutrition.

According to the Global Food Banking Network, an international non-profit focused on alleviating hunger, 900,000 tons of food are wasted or lost yearly in Ecuador. This is an alarming statistic considering that 33% of the population experienced food insecurity between 2018 and 2020 一 a threefold increase since 2014-2016.

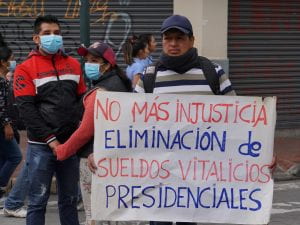

Economic conditions have only been heightened in the pandemic, leading to widespread protests across the nation by indigenous people demanding equitable access to education, healthcare, and jobs. In sum, indigenous people cannot afford to get by, exacerbating existing food insecurity.

Maria Isabel Humagingan, a 42-year-old Indigenous Quichua from Sumbawa in Cotopaxi province described why she was protesting to Aljazeera reporter Kimberley Brown.

“For fertilizer, for example, it used to be worth $15 or up to $20, now it costs up to $50 or $40. Sometimes we lost everything [the whole crop]. So we no longer harvest anything.”

During a time when global inflation is rising, it is the poorest people who are at the most risk. Even those who used to live on subsistence farming are vulnerable. The United Nations Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) found that Ecuador’s food insecurity had risen from 20.7% to 36.8% in one year during the pandemic, and it is apparent that indigenous peoples are the most at risk during this time.

This is not to mention the fact that during a time when global hunger is growing, there is a disproportionate impact on women. Ultimately, food insecurity, while complex and layered, is a mirror of the prejudices and inequalities of society. In order to better understand why and who is impacted, we first need to understand two components: is food available (production and imports), is the food adequate (nutritious), and is food accessible (affordability)?

Factors behind food insecurity in Ecuador and beyond

Environmental Racism

Ecuador has a long history of environmental racism, and for the sake of brevity, we will be focusing on the practices of Texaco/Chevron and its impact on soil fertility.

Victoria Peña-Parr defines environmental racism as,

“minority group neighborhoods—populated primarily by people of color and members of low-socioeconomic backgrounds—… burdened with disproportionate numbers of hazards including toxic waste facilities, garbage dumps, and other sources of environmental pollution and foul odors that lower the quality of life.”

From 1964 to 1990, Texaco (which merged with Chevron in 2001) drilled oil in the Ecuadorian Amazon. Over 16 billion gallons of toxic wastewater were dumped in water sources and unlined open pits left to seep into the soil and devastate clean water sources for people and agriculture. Additionally, 17 million gallons of crude oil were spilled in the disaster now known as “Amazon Chernobyl.” Ecuadorians, a good majority of which were indigenous peoples displaced from their land due to environmental destruction, levied a suit against Chevron which was won in February 2011.

During the judicial process, 916 unlined and abandoned pits of crude oil were found. The human rights implications of this historic case and horrifying disregard for human and environmental safety are lengthy, in order to learn more read this blog by Kala Bhattar.

With this brief background in mind, it is clear to see how this would impact agricultural production, particularly in rural areas where indigenous persons live. Moreover, Afro-Ecuadorians, while only making up 7.2% of the population, are 40% of those living in poverty in the entire country. Most Afro-Ecuadorians live in the province of Esmeraldas, one of the poorest in the country, where most people live off agriculture and “85% of people live below the poverty line.”

UN experts have found that this population is the most vulnerable to environmental racism, suffering from systematic contamination of water supplies and intimidation.

As people suffer through the impacts of a ravaged environment, they must continue to rely on subsistence farming without aid. When crops fail to provide enough economically and for individual families, many go without in this impoverished region.

Climate Change

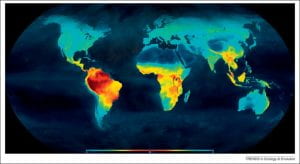

Global warming is leading to changes in weather patterns that have a serious impact on agricultural production 一, particularly in low-income countries that rely on seasonal rains, temperature, and other factors.

Climate change has also led to more severe and deadly disruptions, from hurricanes and earthquakes to monsoons, flooding, and mudslides. Ecuador has been suffering from these climate changes, despite only producing 2.5 metric tons of CO2 emissions per capita (the US comparatively emitted 5,222 million tons in 2020).

Specifically, Ecuador has suffered from a lack of water, specifically irrigation water, landslides, droughts, and heavy rains. The last two aforementioned climate impacts are particularly salient issues as it has impacted seed development by not allowing them to germinate or produce.

In all, the consequences of climate change are having disproportionate effects on low-income states globally in spite of the that they have historically contributed very little to greenhouse emissions. The worst impacts are on nations surrounding the equator and countries with relatively hot climates 一 both of which tend to be low-income countries.

Ukraine War

Due to the ongoing war in Ukraine, food prices have been rising. Ukraine is a leading wheat producer globally. It is the seventh-largest producer of wheat, supplies 16% of the world’s corn, and 40% of the world’s sunflower oil. In the summer of 2022, 22 million tons of grain were stranded in Ukrainian ports, causing mostly low-income countries to feel the growing threat of food insecurity.

Additionally, Ukraine supplied 40% of the World Food Programme’s (WFP) wheat supply. The immediate impact of this is clear in the 45% increase in wheat prices in Africa alone, while any country that receives aid from WFP (which Ecuador has since 1964) is threatened directly by the situation.

As food prices continue to soar, the price of food sold within lower-income nations remains the same, creating a gap between cost and production. The conflict has also led to increases in the price of fuel and fertilizer, leading to food insecurity in many countries beyond just Ecuador. The war in Ukraine has disrupted global food supply chains and led to the largest global food crisis since WWII.

Hunger and the human right to food

There has long been a precedent in the international human rights framework for the right to food, beginning with the first declaration (unanimously accepted) in 1948. In Article 25 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR), the right to an adequate standard of living is guaranteed to everyone with the express mention of food. Fast forward 20 years later, and once more, Article 11 of the International Covenant on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) reiterates (almost identically) the right to food.

The ICESCR actually expounds further on a state’s responsibility to free everyone from hunger, specifically outlining that either individually or through international cooperation specific programs should be developed to address food insecurity and hunger. Moreover, the covenant addresses that food-importing and food-exporting countries should both be reviewed for problems that would impact the equitable distribution of food globally. Lastly, agrarian systems should be reformed to address nutrition and achieve maximum utilization and efficient use of agricultural resources.

In 1999, the Committee on Economic, Social, and Cultural Rights convened to review the progress to end hunger. General Comment 12 reiterated the obligation of states to fulfill the aforementioned responsibilities. Most crucially, however, was the specific mention that states must immediately address issues of discrimination that plague food insecurity. In the case of Ecuador, it is clear that this remains a salient issue.

Most recently, in 2015, during a historic UN summit, world leaders adopted 17 objectives to be achieved by 2030. Known as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the second objective is to create a “Zero Hunger” world by 2030.

Conclusion: Fighting Food Insecurity

According to the World Food Program, 60% of the world’s hungry live in areas afflicted by conflict. There is no simple way to end a conflict, but it is crucial that all states remember their commitments to the SDGs and ICESCR. This means that states need to step in to provide nutritious food when a home state will not or cannot. Just like Red Cross, journalists, and other humanitarian organizations are protected by international humanitarian law from being targeted in conflict, so too should persons ensuring food access to people. Moreover, countries should address the factors that contribute to food insecurity such as environmental racism and climate change.

There is no one solution for this issue since there is no single cause. However, by refusing to accept these conditions, learning more about the causes and conditions of food insecurity, and demanding more, we can begin to bring about a world that truly is free from hunger.

- Food Insecurity in Birmingham, AL by Mary Bailey

- America: The Land of the Hungry by Kala Bhattar

- The Right to Food: A Government Responsibility by Zee Islam

- Donate to the World Food Program

- Learn more and get directly involved with SDGs

- Follow @uab_ihr for Speaker events, blogs, and to learn more about supporting human rights locally and globally