“Armed conflict kills and maims more children than soldiers,”

-Garca Machel, UNICEF

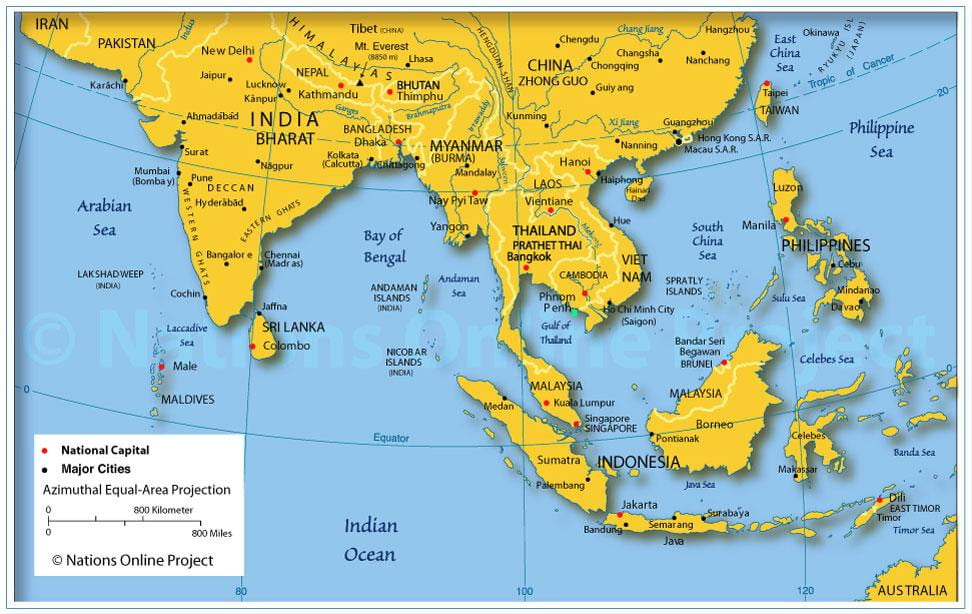

Global unrest and armed conflict are becoming more common, intense, and destructive. Today, wars are fought from apartment windows, in the streets of villages and suburbs, and where differences between soldiers and civilians immediately vanish. Present day warfare is frequently less a matter of war between opposing armies and soldiers than bloodshed between military and civilians in the same country.

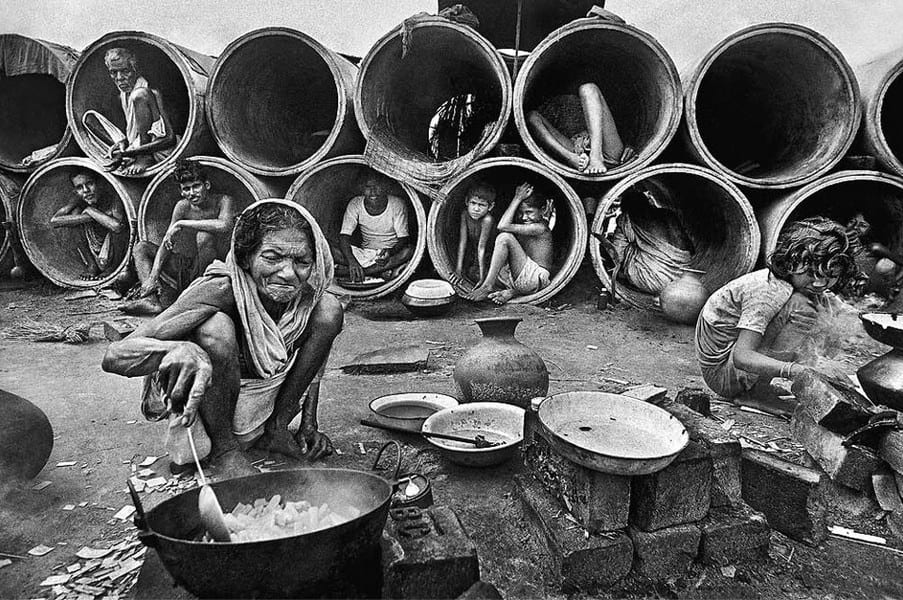

In 2014, there were 42 armed conflict, resulting in 180,000 deaths worldwide. Civilian death tolls in wartime increased from 5 per cent at the turn of the century to more than 90 per cent in the wars of the 1990s. War and armed conflict is one of the most traumatic experiences any human can endure, and the brunt of this trauma is felt by civilians- most especially children. In 2015 alone, some 75 million children were born into zones of active conflict. As of May 2016, one in every nine children is raised in an active zone of conflict. Two hundred and fifty million young people live in war zones, with the number refugees at its most prominent since World War II. Currently, there are 21.3 million refugees worldwide, and half of them children.

For refugees, the events leading up to relocation (notably war and persecution), the long and unsafe process of relocation, settlements in refugee camps, and overall disregard for human rights, takes a major emotional and mental toll. PTSD, depression, anxiety, and sleeping disorders are just few of many problems refugee children experience. Respecting human rights is essential to society’s overall mental health. Equally, a society’s mental health is essential for the enjoyment of basic human rights. Addressing the psychological needs of victims of armed conflict is essential for the prosperity of war-battered children’s future.

The Relationship between Mental Health and Human Rights

Armed conflict affects all aspects of childhood development – physical, mental, and emotional. Armed conflict destroys homes, fragments communities, and breaks down trust among people, thereby undermining the very foundations of most children’s lives. The psychological effects of loss, grief, violence, and fear a child experiences due to violence and human right violations must also be considered.

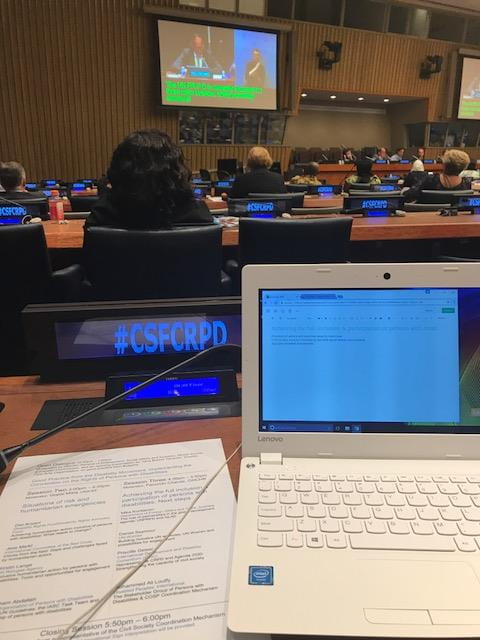

Throughout the process of becoming a refugees, the three main stages in which people experience traumatic and violent experiences include: 1) the country of origin, 2) the journey to safety, and 3) settlement in a host country. The interrelationship between human rights and mental health are recognized in various universal human right conventions and resolutions. Numerous legislative measures exists for mental health, but two main conventions that address the situations refugees experience include: 1) Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment and 2) The Convention on the Rights of a Child. These two conventions specially address mental health pertaining to violence.

Convention against Torture and Other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment: 1987

This Convention is significant towards the promotion of mental health as a human right because “torture,” any act that creates severe pain or suffering, can be both physical and mental. This convention is particularly relevant to refugees because they are more vulnerable and susceptible to mental and physical torture. The short video documentary released by the UNHCR provided refugees and migrants to tell their own stories of kidnap and torture during their journeys to Europe. The stories told by survivors are emotionally distressing but highlights the realities refugees continuously experience.

The Convention on the Rights of a Child: 1990

The Convention on the Rights of a Child is the first legally binding international instrument to integrate the full array of human rights. This convention is also an important document for mental health. The CRC explicitly highlights the significance of both the physical and psychological wellbeing of a child. This convention is particularly important because it addresses the relationship of affect armed conflict on mental health. First, Article 38 of the Convention highlights state parties’ obligation under international humanitarian law to protect the civilian population in armed conflicts, and shall “take all feasible measures to ensure protection and care of children who are affected by an armed conflict.” International humanitarian law is a set of rules which aim, for humanitarian purposes, to minimize and protect persons from the effects of armed conflict. Second, Article 39 of the Convention states “States Parties shall take all appropriate measures to promote physical and psychological recovery and social reintegration of a child victim of: any form of neglect,… torture or any other form of cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment; or armed conflicts.” For children refugees, the Convention on the Rights of a Child is an imperative document for the security of their right to mental health, and mental health services.

Barriers to Accessing Health Care Services

The process of becoming a refugee takes a tremendous emotional and mental toll on all refugees. PTSD, depression, anxiety, and sleeping disorders are just few psychological diagnoses given to refugee children. The fundamental right to mental health care is addressed in various international standards, such as the Convention of the Rights of the Child, however, there continues to be numerous barriers preventing access to these services. There has been an unparalleled surge in the number of refugees worldwide, the majority of which are placed in low‐income countries with restricted assets in mental health care. Currently, responsibility for mental health support to refugees is divided between a network of agencies, including the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), the World Health Organization (WHO), government, and nonprofit organizations. Yet, the reality is that most refugees with mental health problems will never receive appropriate services. Cultural barriers, such as language, persistently affect a refugee’s capability to utilize mental health series. A study examining health care barriers of post-settlement refugees reveals language is the most impeding cultural barrier to accessing healthcare. Refugees and mental health service providers often do not speak the same language, making successful communication during healthcare visits less effective. Language barriers affect every level of the healthcare system, from making an appointment to filling a prescription. A lack of multilingual interpreters for refugees and health care providers weakens the healthcare system, making miscommunication about diagnoses and treatments possibilities common. Lastly, stigma surrounding mental health is another barrier to health services. Refugees often feel the words “mental health issues” should be reserved for individuals with extreme learning disabilities, and do not understand mental health problems can be conditions like depression and anxiety.

Psychopathologies due to trauma are very powerful, however, recovery is possible. In Judith Herman’s book Trauma and Recovery, she discusses her theory of recovery. She states recovery happens in three stages: 1) establishment of safety, 2) remembrance and mourning, 3) re-connection with ordinary life.

Stage 1: Safety

Trauma diminishes the victims’ sense of control, power, and overall feeling of safety. The first stage of treatment focuses establishing a survivor’s sense of safety in their own bodies, with their relations with other people, in their environment, and even their emotions. Self-care is also an important focus point during this stage. The purpose of this stage is to get victims to believe they can take protect and take care of themselves, and they deserve to recover.

Stage 2: Remembrance and Mourning

The second stage of Herman’s recovery theory highlights the choice to confront trauma of the past rests within the trauma survivor. It’s important for victims to talk about their goals and dreams before the trauma happened so they can reestablish a sense of connection with the past. That second stage begins by reconstructing the trauma beginning with a review of the victim’s life before the horrors and situations leading up to the trauma. This second step is to reconstruct the traumatic event as a recitation of fact. The goal of this step is to put the traumatic event into words, and come to terms with it. Testimonies are ways for survivors to get justice, feel acknowledged, and find their voice.

Stage 3: Reconnecting

In the final stage, the victim focuses on reconnecting with oneself and the recreation of an ideal self that visits old hopes and dreams. The third stage also focuses on emotionally and mentally reconnecting with other people and social reintergration. By this stage the victim should have the capacity to feel trust in others. A small but influential minority of individuals revolutionize the meaning of their trauma and tragedy, and make it the foundation for social change.

A Peaceful Future

Even though human rights activists are not psychological clinicians, we can still contribute to the success of these stages. At present, more than half of the refugee children population are children. Despite the violence these children have experienced, refugee children are the foundation and hope for a peaceful future. However, for that to happen, refugee children need to find peace in themselves. Respecting human rights is essential to society’s overall mental health. As activists we need to advocate for refuges and children who don’t have a voice. Activists for human and mental health rights should start focusing their goals on ensuring their communities and hospitals contain mental health care provisions. As activists, we can lobby for more accessible mental health services throughout our health care system, join and volunteer at non-profit organizations, and advocate for the rights of refugees. As Herman Melville states, “we cannot live only for ourselves. A thousand fibers connect us with our fellow men.”