The United Nations (UN) Conference on State Parties (CoSP10) experience began on the 29th floor for me. I say this because I lived in New York City and toured the UN on a couple of occasions. Additionally, living a life that is inclusive of persons with disabilities is in my wheelhouse. A friend and mentor utilizes crutches to help him walk because an accident, when he was younger, took the full use of his legs. Cancer took the use of B’s legs when she was a baby, and a motorcycle accident left my uncle paralyzed from the waist, making them both wheelchair users. I lead with all of this to say that making room in my world for persons with disabilities is something I have done for decades. My familiarity, in a sense, is akin to the knowledge gained by a couple of tours of the UN lobby and gift shop. Therefore, walking into CoSP10, I was prepared or so I thought.

I had never been on the 29th floor. The perspective is much different up there.

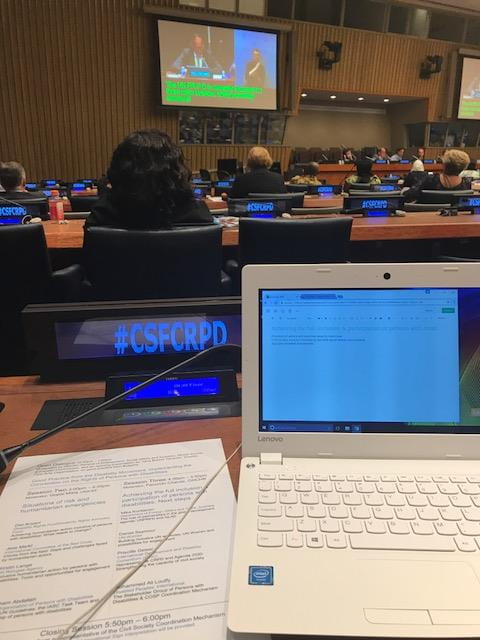

The Division of Economic and Social Affairs (DESA) is located on the 29th floor of the UN. The DESA team is responsible for both the economic and social affairs of persons with disabilities for all the UN member states as directly related to the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). They write and disseminate policies and ideas to the member states as suggested modes of implementation. Each policy and suggestion lies within the UN mandated Sustainable Development Goals (SDG) which is an extension of the 1945 UN Charter. SDGs are the 17 goals all member states, through collaboration, seek to achieve by 2020 as a means of ensuring “no one is left behind” while honoring the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) and CRPD. Sitting in the conference room, I am inspired by the opportunity but not fully awake to what is about to take place.

Enter Daniela Bas.

Bas is the DESA director. During her chat with us, she disclosed a couple of points that stand out to me. First, the UN, as an employing entity, is beginning to put into action many of the policies and measures, tasked to member states for implementation. Most specifically, employing persons with disabilities in key leadership positions of which she is one. Second, the UN is an organization led by human beings seeking to do the right thing. With full acknowledgment, she reminds that the UN is not perfect but that the process of coalescing 196 backgrounds, traditions, religious affiliations, and attitudes to make significant strides at securing human rights and making the world more peaceful, is an accomplishment. Lastly, when compared to men and boys, and those who are able-bodied, discrimination against women and girls with disabilities doubles, and even triples if they belong to a minority race or class in their country. This last point, triple discrimination for women and girls with disabilities will become a recurring theme in the conference for me. The harsh reality of this fact remains an echo in my soul to this moment.

Confrontation with another person’s truth requires an adjustment to what is known through experience and education, and assumed through familiarity.

I study and view life and the world with a gendered perspective in mind. I look for the role of women, our impact on families and societies, and our visibility and invisibility when it comes to equality. I am aware of the trials of living life at intersections. Intersectionality complicates because discrimination is complicated. I believe there is a temptation to separate the intersections so to obtain a solid understanding; however, it is in the attempt to separate that understanding is lost. Gaining a complete understanding of the dynamics of discrimination requires a holistic not segmented perspective.

Girls, irrespective of ability, are not as valuable or visible in many societies as boys are. Nora Fyles, head of the UN Girls Education Initiative (UNGEI) Secretariat, asserts invisibility is the fundamental barrier to education for girls with disabilities. She confirms this assertion when explaining the search for partnership on the gendered perspective education project by stating that 1/350 companies had a focus on girls with disabilities. For Bas, the failure to identify girls and women with disabilities is a failure to acknowledge their existence. Subsequently, if they do not exist, how can we expect them to hear their need? She suggests addressing crosscutting barriers. Leonard Cheshire Disability (LCD), in partnership with the World Bank, UNICEF, and UNGEI, hosted a side-event where they released their findings regarding a lack of inclusive education opportunities for girls with disabilities. Still Left Behind: Pathways to Inclusive Education for Girls with Disabilities sheds light on the present barriers girls, specifically those with disabilities, experience when seeking an education.

Article 26 of the UDHR lists education as a human right. Bas believes if knowledge is power, and power comes from education, the fact that 50% of women with a disability complete primary school and 20% obtain employment, reflects social and economic inequality. Ola Abu Al-Ghaib of LCD emphasizes policies, cultural norms, and attitudes about persons with disabilities perpetuate crosscutting barriers for girls with disabilities to receive an education. She concludes that schools are a mirror of society. In the absence of gendered sensitivity, boys advance and girls do not. Every failed attempt to address and correct the issue is a disservice to girls generally, and girls with disabilities, specifically.

It is imperative to remember that the spectrum of disability is multifaceted. Most people recognize developmental and physical disabilities like Downs Syndrome, Autism, visual and hearing impairment, and wheelchair users, but fail to consider albinism and cognitive disabilities as part of the mainstream disability narrative. Bulgaria is focusing on implementing Article 12 of CRPD regarding legal capacity. Legal consultant and lawyer, Marieta Dimitrova explains that under Bulgarian law, only reasonable persons have the right to independence; therefore, persons with cognitive disabilities receive the “unable” descriptor under assumption they are unable to reason and understand, thereby placing them under a guardian. Guardianship removes the right to participate in decisions regarding quality of life, which is a deprivation of liberty. She resolves that although full implementation into law awaits, stakeholders are seeking renewal in the new government because pilot projects have proven that an enjoyment of legal capacity in practice yields lower risk of abuse, changed attitude within communities, personal autonomy and flexibility.

Not all disabilities result from birth or accidents. War and armed conflict factor into 20% of individuals maimed while living in and fleeing from violence. A lack of medical access leave 90% of maimed individuals permanently disabled. Stephane from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) submits that for refugees with disabilities, access to essential services can be difficult on the journey and in camps, but also for those who are unable to flee. He infers a “double disability” inflicted upon refugees with disabilities: first as a refugee, and second as a person with a disability. Human Rights Watch advocates that refugee camps produce a humiliating and degrading existence for persons with physical disabilities because the “tricks” employed prior to arrival in the camps, are no longer applicable as wheelchairs sink in the mud and crutches break on rocky grounds. The Lebanese Association for Self-Advocacy (LASA) reports the underrepresentation of women and girls is significant when receiving information and access to assistance.

In a refugee simulation seminar, LASA informed that on the ground, confusion is high given that humanitarian organizations do not consult with each other, making communication difficult and non-supportive. For families with a person with a disability, nonexistence communication means a prevalence to fall victim to violence and harassment. Jakob Lund of UN Women divulges that humanitarian aid can be ineffective for women with disabilities, while Sharon with OHCHR suggests a clear dichotomy between the rights of the able-bodied and the rights of persons with disabilities holds central to the ineffectiveness. At the core of a lack of communication and accessibility is invisibility. Stephane concludes that there is an obvious need for a necessary and systematic retraining specific to educating others on how to see the invisible.

The process of inclusion and equality relates directly to the decision to acknowledge a person’s existence. Retraining the mind to see any human being with a physical disability takes decisive action so I put myself to the test. First, I thought of all the famous women with a physical disability I could think of, and arrived at about six, including Heather Whitestone and Bethany Hamilton. I then googled celebrity women with disabilities which yielded a Huffington Post piece that identified Marlee Matlin, Frida Kahlo, Helen Keller, and Sudha Chandran as 4/10 “majorly successful people with disabilities”. I had Marlee Matlin and Helen Keller. What is more interesting is that I arrived at seven when naming men with physical disabilities. Here is the point: society is not inclusive of persons with disabilities if we have to strain our brains to remember the last time we sat next to, opened the door for, ate a meal with, or saw on the television/movie screen/church platform a person who did not look like us physically.

Perspective changes everything because perspective is everything.