By Pamela Zuber

“We have to reform a system of criminal justice that continues to treat people better if they are rich and guilty than if they are poor and innocent.” – Bryan Stevenson, founder of Equal Justice Initiative and author of Just Mercy

Money can’t buy happiness, but does it buy justice? Or, more accurately, does it help people avoid justice? Does money provide unfair advantages?

Athlete and actor O. J. Simpson famously assembled a team of some of the most prominent lawyers in the United States to defend him after he was accused of killing his ex-wife and her friend. Dubbed a legal dream team, these defenders helped Simpson win acquittal on criminal charges in 1995, although he was convicted of civil charges in 1997.

Wealthy financier Jeffrey Epstein could have been convicted of federal sex crimes involving teenagers in 2008 but pleaded guilty to lesser charges in a Florida state court. During his sentence, he was allowed to leave prison for up to twelve hours every day for six days a week. Epstein also had private security and his own psychologist while staying in a private wing of a Miami prison.

After serving thirteen months, Epstein traveled frequently to New York and the Virgin Islands while he was on probation. Epstein committed suicide in prison in August 2019 while awaiting trial on charges of sex trafficking and conspiracy to commit sex trafficking. The trafficking trial continued after his death.

Did Simpson and Epstein’s money, power, and connections help them avoid justice? If so, what does that mean for the average person and can we do anything to change it?

Understanding poverty and imprisonment

“In all criminal prosecutions, the accused shall enjoy … the assistance of counsel for his defense.”

– Sixth Amendment of the United States Constitution

“If you cannot afford a lawyer, one will be provided for you.”

– Description of Miranda warnings issued to suspects

According to the U.S. Constitution and the 1966 U.S. Supreme Court ruling Miranda v. Arizona, people accused of crimes have the right to obtain an attorney for their defense. Wealthier people have the financial resources and social connections that allow them to hire experienced private attorneys. If people cannot afford such legal assistance, they may defend themselves or receive the help of court-appointed attorneys.

Although court-appointed attorneys are sorely needed, the system that employs them has experienced major problems. According to the Equal Justice Initiative, “[p]oor people in most jurisdictions do not get adequate legal representation. Only 24 states have public defender systems, and even the best of those are hampered by lack of funding and crippling case loads.”

Even if they secure representation at trials, poor people often cannot afford attorneys to represent them at appeals and other legal system procedures. Well-heeled suspects, meanwhile, can often better afford experienced representation throughout the judicial process and other benefits of such representation.

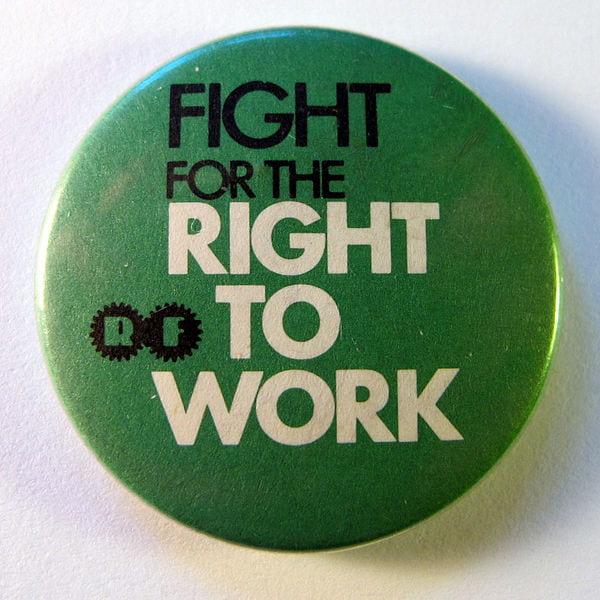

“People in prison and jail are disproportionately poor compared to the overall U.S. population,” noted the Prison Policy Initiative. “Poverty is not only a predictor of incarceration; it is also frequently the outcome, as a criminal record and time spent in prison destroys wealth, creates debt, and decimates job opportunities.” Even after poor people leave prison, their punishment continues. Poor people who are convicted of crimes often find it difficult to find jobs, housing, and other opportunities after they serve their sentences.

Much of this prosecution and imprisonment relates to drugs. “Over 1.6 million people are arrested, prosecuted, incarcerated, placed under criminal justice supervision and/or deported each year on a drug law violation,” reported the Drug Policy Alliance.

While some people turn to selling drugs when they feel they have few other economic opportunities, that is not the case for many people arrested for drug violations. People may face severe penalties just for possessing drugs for their own personal use. If they’re poor, they’re less likely to have access to effective addiction treatment, so they have a greater chance of staying addicted. There is a greater likelihood that the police will catch them with drugs in their possession.

Once arrested, poor people face medical and psychological problems relating to their addiction. They face criminal and financial problems due to their arrest, incarceration, defense, and trial. Such problems often make poor people even poorer.

Making the legal system fairer

Some areas are looking for ways to make justice fair for all, not just the more financially secure. Writing for the Wisconsin Center for Investigative Journalism and Wisconsin Public Radio, Emily Hamer and Sheila Cohen stated that “[t]he Wisconsin Constitution states cash bail can be used only as a means of making sure the accused appears for the next court hearing — meaning judges are not supposed to consider public safety when making decisions about bail.”

Similarly, in 2018, former California governor Jerry Brown signed Senate Bill 10, a measure that would have abolished cash bail in the state. The state’s bail bonds industry struck back. It collected enough signatures to make this measure a 2020 ballot referendum so voters could determine its validity. Between the 2018 bill signing and the 2020 referendum, some California courts and reformers worked to promote changes to California bail practices and courts.

Representation may be becoming fairer as well. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) investigated legal representation in the state of Michigan and found it wanting. In response, the state created the Michigan Indigent Defense Commission in 2013. The commission pays for staff members and training for cases and creates standards for court-appointed attorneys.

Michigan’s commission also includes a useful FAQ section on its website to help people understand and navigate the court-appointed attorney process. It describes how court-appointed attorneys must visit clients who have been jailed within three days, for example, and explains other rights of the accused.

Investigating laws and how they impact people

U.S. states are also investigating laws to determine if they’re fair to all of their residents. Many states have mandatory minimums, which are mandatory minimum sentences that people must serve if they’ve been convicted of certain crimes. According to the U.S. Sentencing Commission, during the 2016 fiscal year, African American and Hispanic people were more likely to be convicted of offenses that garner mandatory minimums.

The conviction rates of these groups don’t match their overall representation in the U.S. population. While Hispanic or Latino people accounted for 40.4 percent of the people convicted of mandatory minimum crimes in 2016, U.S. Census estimates from 2018 placed the Hispanic or Latino population of the United States at 18.3 percent. The U.S. census estimated the African American or black population as 13.4 percent in 2018, but people in this group accounted for 29.7 percent of mandatory minimum crime convictions.

Black and Latinx people traditionally have made less money than white people and continue to do so. The U.S. Census Bureau reported that in 2017, the median average income for households who identified as white and not Hispanic was $68,145. For Hispanic households, the median income was $50,486, while the median income for black households was $40,258.

Lower incomes have traditionally meant that people were less likely to afford adequate legal assistance. They were forced to turn to overworked, underfunded legal defense programs for assistance, assistance that may have not had the time or financial resources to investigate and defend their cases. If their legal representation faced better financed opposition, accused people may have been more likely to lose their cases, serve lengthy prison sentences, and endure unbreakable cycles of poverty after their releases.

Changes such as bail reforms in Wisconsin and California and the creation of the Michigan Indigent Defense Commission hope to end such unfair outcomes. They strive to make legal representation accessible to all. They aim to make justice truly just.

About the author: Pamela Zuber is a writer and an editor who has written about various topics, including human rights, health and wellness, gender, and business.

Moja & Billie (Mbili) –

Moja & Billie (Mbili) –