My week spent in Kenya was amazing and profound, yet I find myself at a loss for words when trying to describe my time there.” I have been told that I am not a good storyteller. Details of the stories I tell that seem crucial to me turn out to be utterly unimportant to others, often causing them to lose interest and miss the significance of my experiences. Upon my return from a week-long study abroad trip to Kenya, I was asked all the predictable questions that one receives after a travel excursion: What did you do? How was it? Did you love it? Will you return? Can you tell me more about your trip? These are the questions that I cannot answer…how do I summarize a week’s worth of moments into interesting, well-constructed narratives that completely capture the beauty and wealth of knowledge I learned while away?

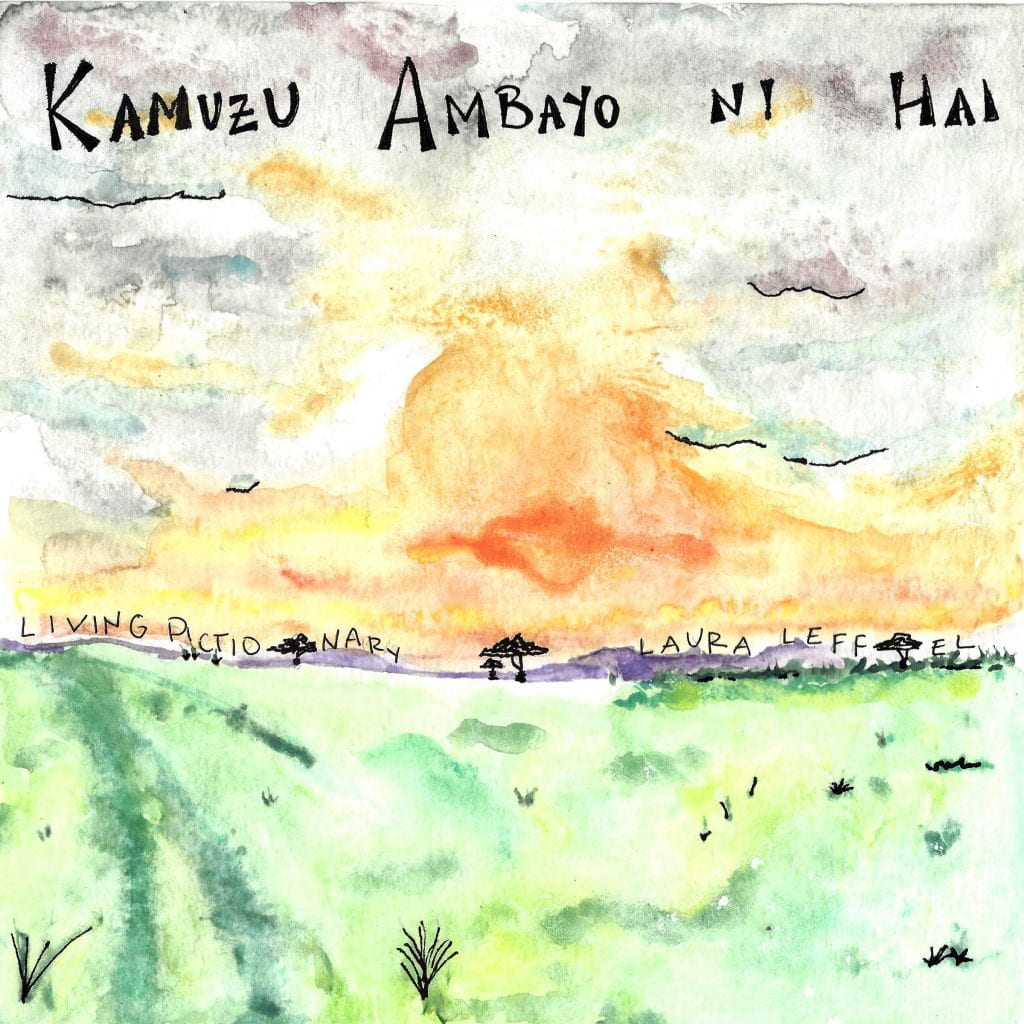

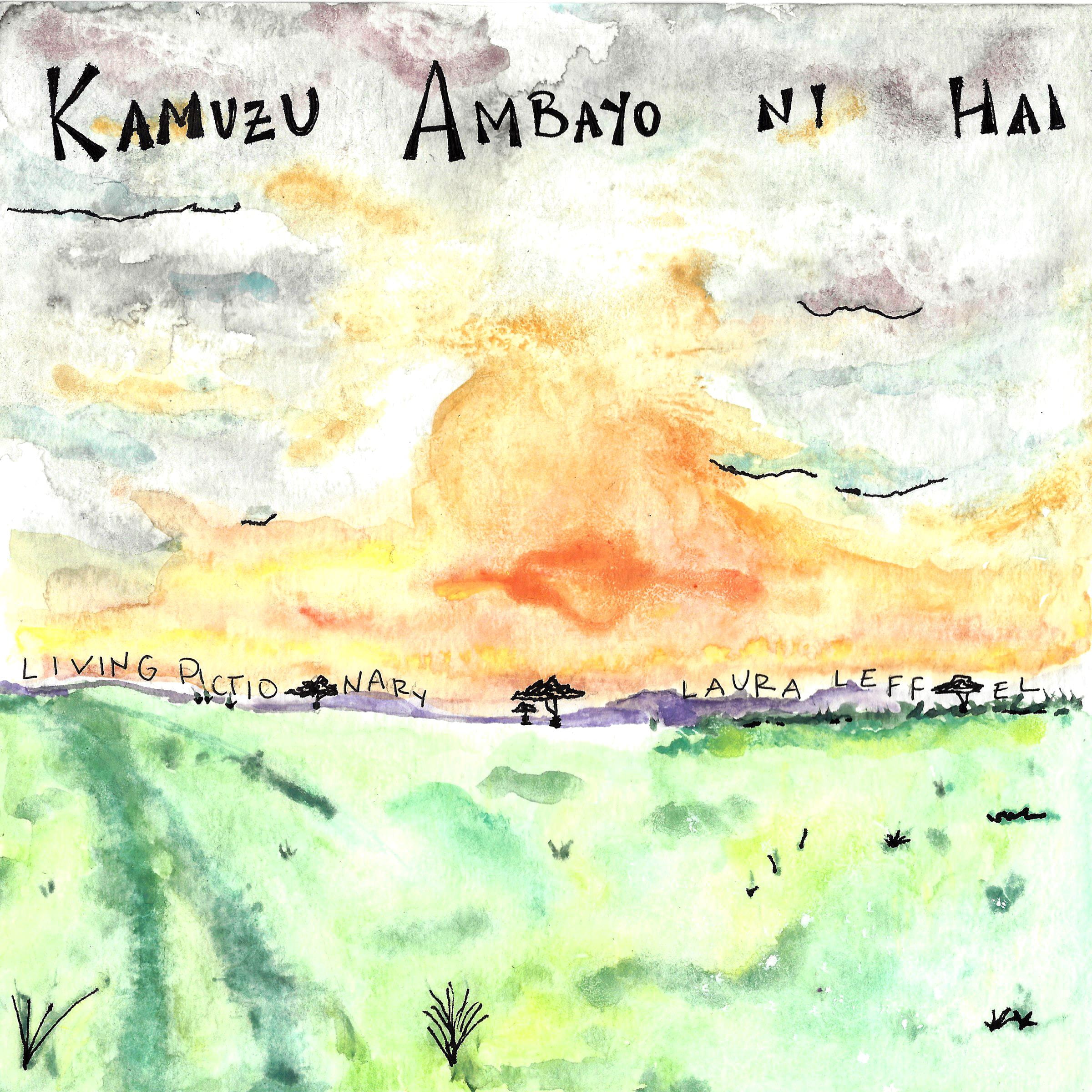

The truth is I can’t, so I don’t, leaving both me and my friends unsatisfied. So when my professor who led the trip to Kenya reminded us of our living dictionary assignment, my plan began to take form. The Living Dictionary assignment was to select words in Swahili and translate them to English and turn in that list of words we had collected while there. Nelson, who started the camp and worked tirelessly to coordinate our trip and helped me translate the words for my Living Dictionary. This is not a commonly used phrase – in the United States or otherwise, so it took Nelson a minute to compose it. My mind starting whirling as to how I could take the assignment and make it into an art project. I realized that each day of my trip could be summarized into two Swahili words, and those words could tell the stories of my trip, along with accompanying the artwork.

While I was in Kenya, I chose nine words and phrases to tell the stories of my experience. Then I created images to accompany the words using different art mediums. These phrases and words were translated for me by the people I met while I was in Kenya. I found it liberating to express my experiences through creativity, and then use those art pieces to tell a story of my time abroad. Organizing my thoughts through the words and pictures ordered the information I shared. Reflecting on my week in Kenya, I knew there was some core knowledge I had observed while there that left an impact on me, I wanted to leave an impact with this art.

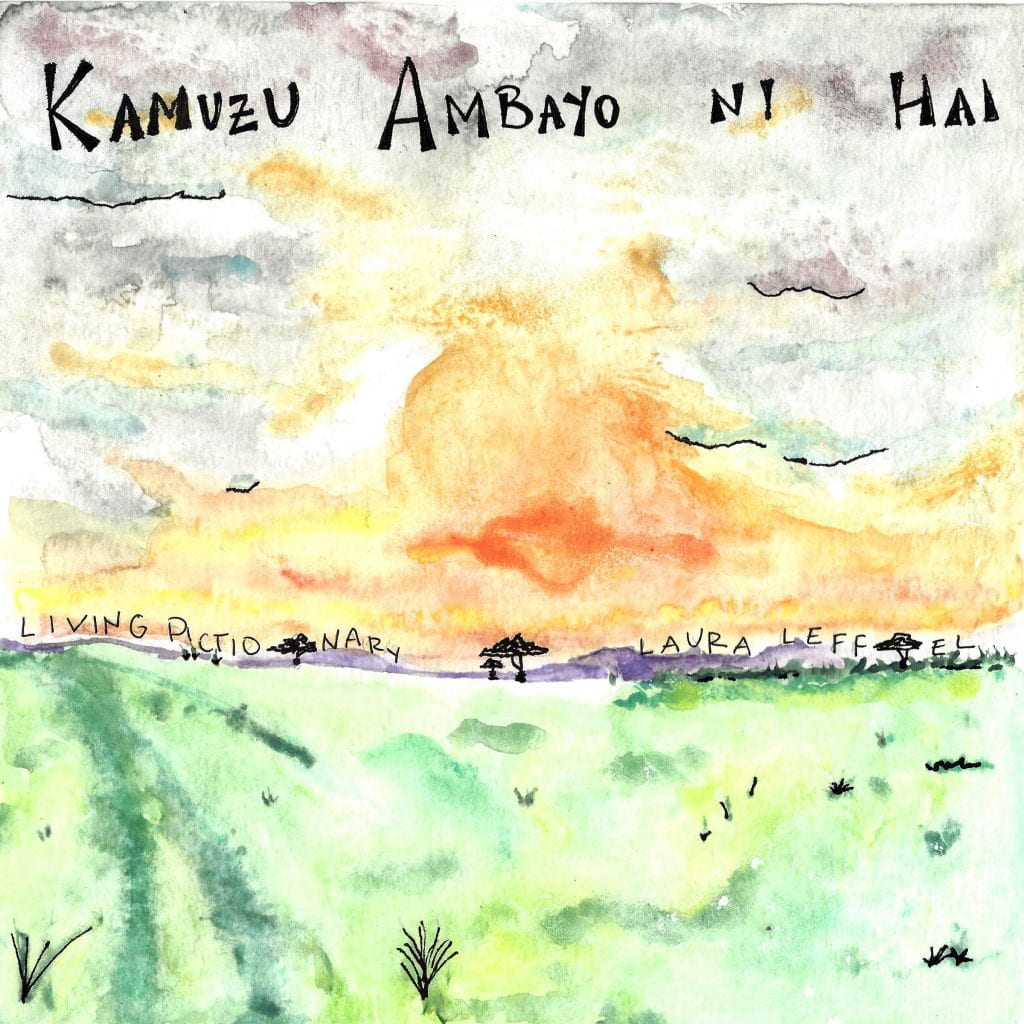

Kamuzu ambayo ni hai – “Living Dictionary”

The watercolor is inspired specifically by an image from the safari we took; however, it also represents the vibrancy of color in the Kenyan landscape. We spent a majority of our time in Kenya out in the Maasai Mara, which is about four hours from Nairobi. There we stayed at Oldarpoi Camp, a sustainable tourism camp run by the community for the community. On the safari, I saw animals in their environment and on their own terms. The land and animals there are demonstrating an authentic ecosystem, something I have never seen firsthand before. My lion and elephant viewing could be confined to the zoo, but the safari was the antithesis of the zoo. There were no glass windows separating the animals from the observer, nor regularly scheduled feeding times. It was as if I stepped into a city where the skyscrapers were trees and sidewalks were flowers and bushes. Like any great city my presence did not interrupt its typical course, nor will my individual presence ever be remembered by the occupants. The natural beauty of this place never failed to leave an impression on me.

Moja & Billie (Mbili) – “One” & “Two”

Moja & Billie (Mbili) – “One” & “Two”

The image I chose to depict these words was inspired by all of the nights I spent looking out from the window above my bed. I could always see the milky way, and it was an unreal, magical sight that I have never been able to appreciate while in the States. Looking up at the universe I saw light and contrast that I cannot name or begin to understand. I could not tell you why stars burn in the night or the difference between celestial planets, but that does not mean I cannot appreciate it. I ended each day in Kenya grateful and full of love for all that I had seen and learned, even if I had not yet begun to process it. Like this trip, those evenings staring at the expanse was a singular experience The highlight of my evening was when I picked out Orion’s belt, a constellation made of three stars. It was so clear and easy to pick out that I wanted to add it into this piece.

On our first day in Kenya, as we were driving out to the Mara, we stopped on the side of the road at a shop. There, I met Joseph, who taught me how to count in Swahili. This is the first of many instances where my English ears did not hear or understand the nuances of the language. Two in Swahili is spelled “mbili,” but to my ears, it always sounded like “billie.” Language was an important tool to use when making a connection with others in Kenya. I often did not speak the same language as them, but something I have found to be true everywhere, in the United States and Kenya, was that others are eager to teach. Never once did I ask how to say or spell something in Swahili and the response was “No.” Each time, the person gleefully and patiently waited with me as I stumbled over sounds trying to repeat what they were teaching me. Not only did I learn Swahili words from this, but I learned the power of teaching and how it provides connection and bonds with humans.

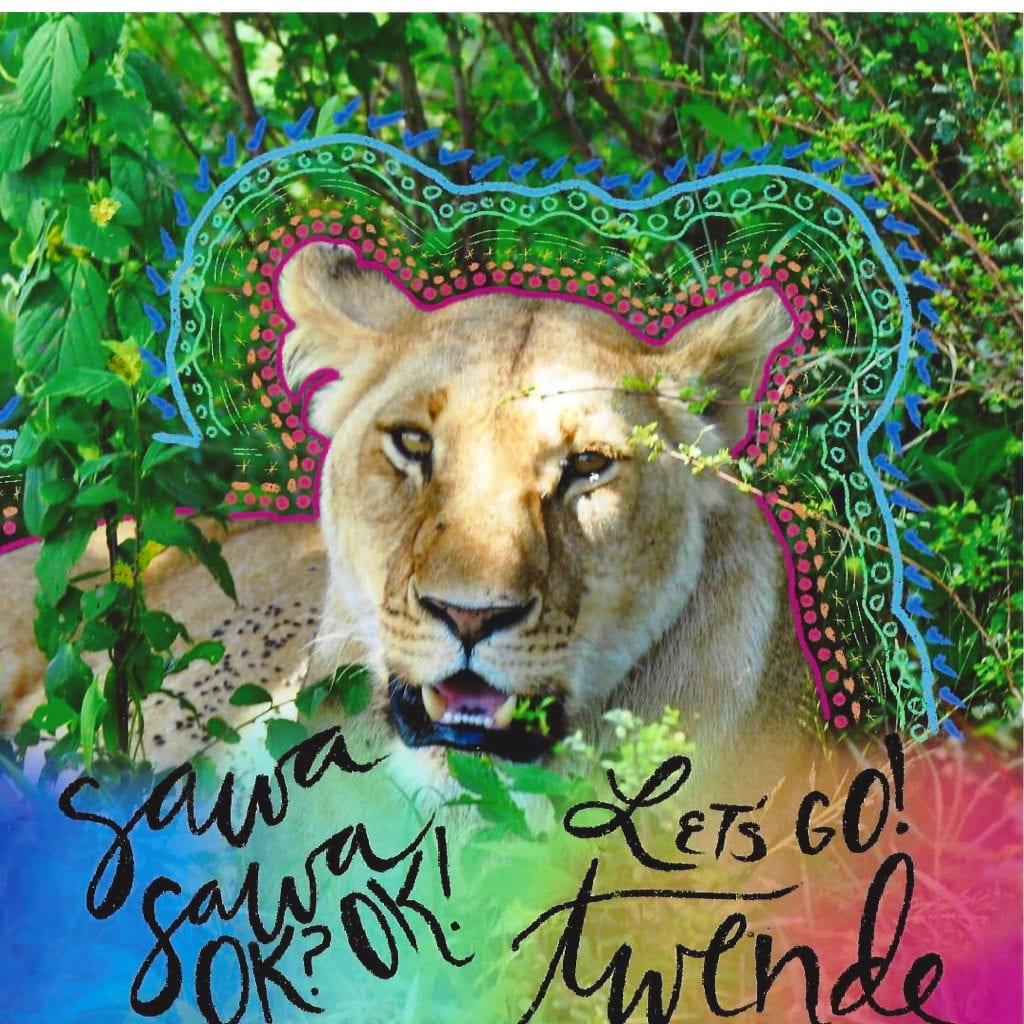

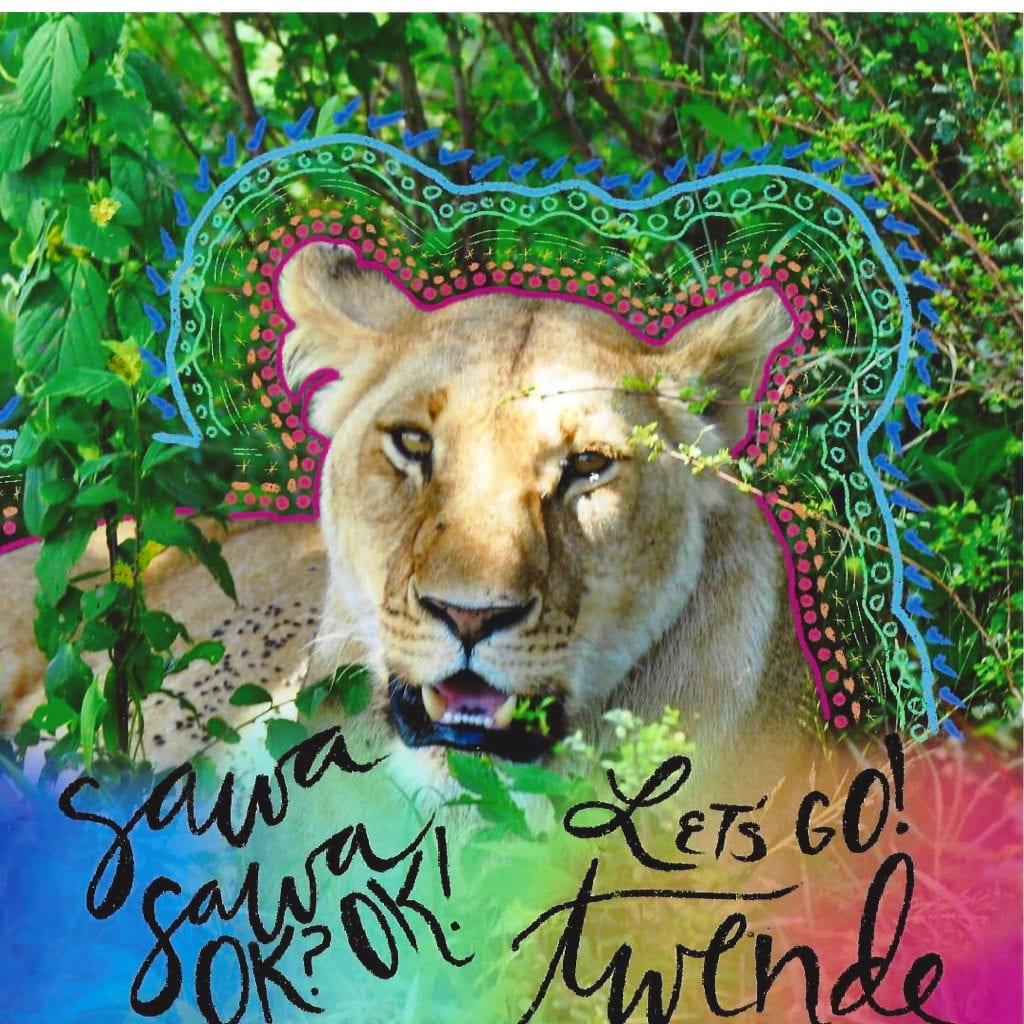

Sawa Sawa & Twende – “Ok? Ok!” & “Let’s go!”

During our trip, Sam and Joel not only drove us all over the country but also became our friends and guides. They fearlessly leading us all over the Mara through a safari. They knew so much about the creatures we were seeing. They knew where they would spend time and were able to find the best spots for viewing. Whenever we would stop to look at an animal, Sam would ask us, “Ok?” and we would all respond “Ok!” letting him know we were ready to move on. Sam was an expert driver and wild animal spotter as we witnessed many animals such as lions, giraffes, zebras, and warthogs in their natural habitat.

Much of the way people make money is through tourism, and often the safaris and the promise of animals is what brings the tourists. In order to see the animals up close, it is vital that you respect and understand their patterns and habits.

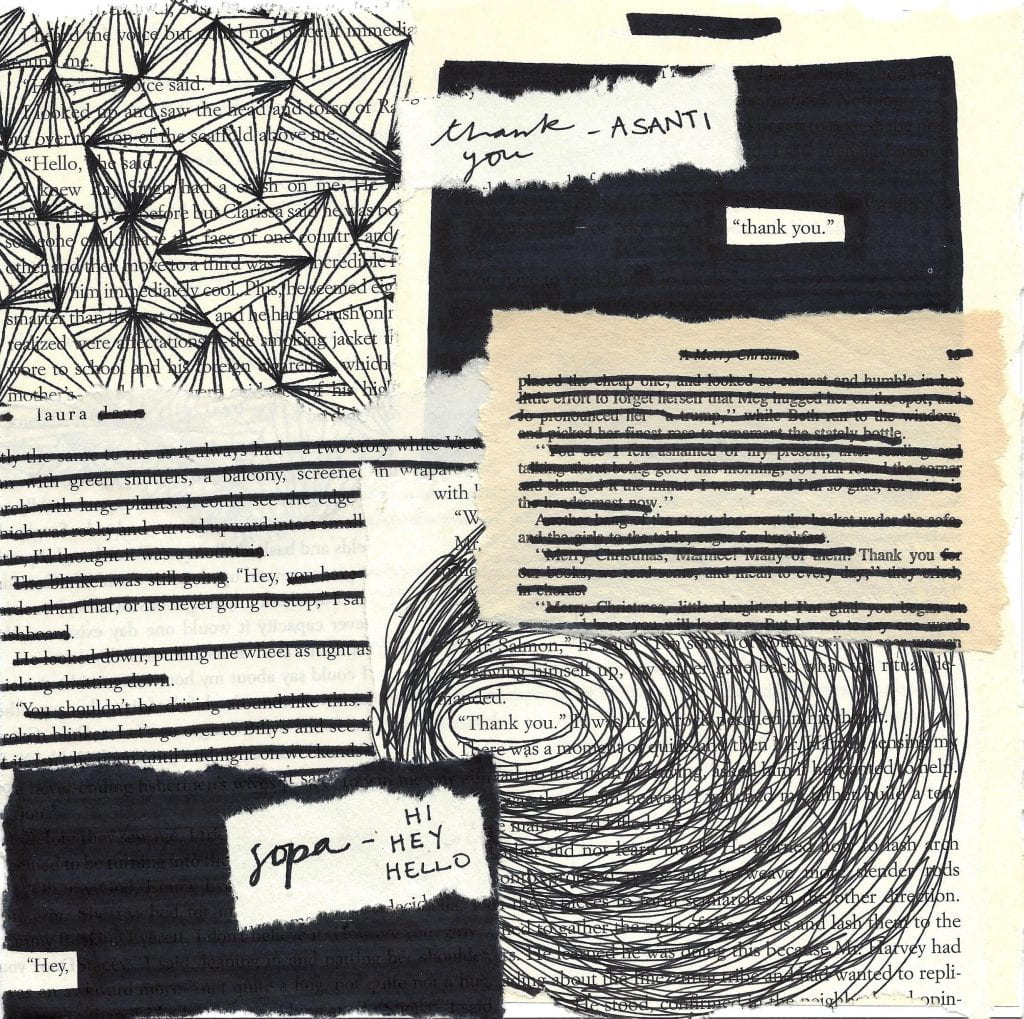

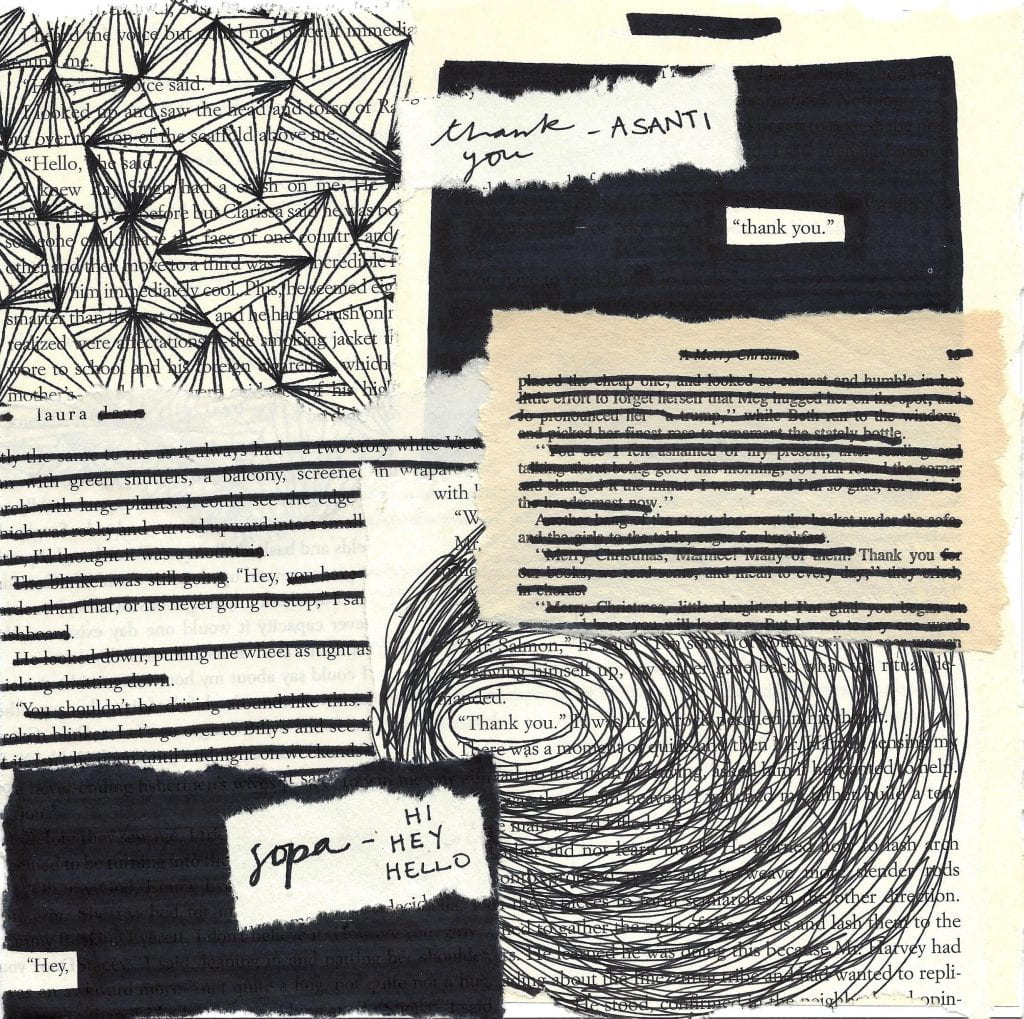

Sopa & Asanti (Asante) – “Hi” “Hey” Hello” & “Thank you”

A majority of people that I met while in Kenya were able to speak three languages: English, Swahili, and their local dialect. We were staying in the Maasai lands where they speak Maa, which is that region’s local language. A common greeting for them is “Sopa” or hello. When we first arrived at the Oldarpoi camp, we were greeted by the people sharing their culture and traditions with us. They always warmly welcomed us with a friendly “Sopa”. When beginning to learn a new language it seems that some of the first phrases you pick up are how to welcome and how to be grateful. This made “Thank you” a vital phrase, and gratitude a universal concept, which is one of the most insightful realizations I had while in Kenya. I might not speak the same language as them, or fully understand their culture, but there are mutual understandings of humanity that persist across cultural boundaries. The sound of children laughing and playing is the same in any country. Friends teaching each other popular dances is the same in any country. Being grateful for life and connection is the same in any country. Asanti, or Asante as it is correctly spelled, was given freely and frequently during our time there. How could it not be? We had so much to be grateful for.

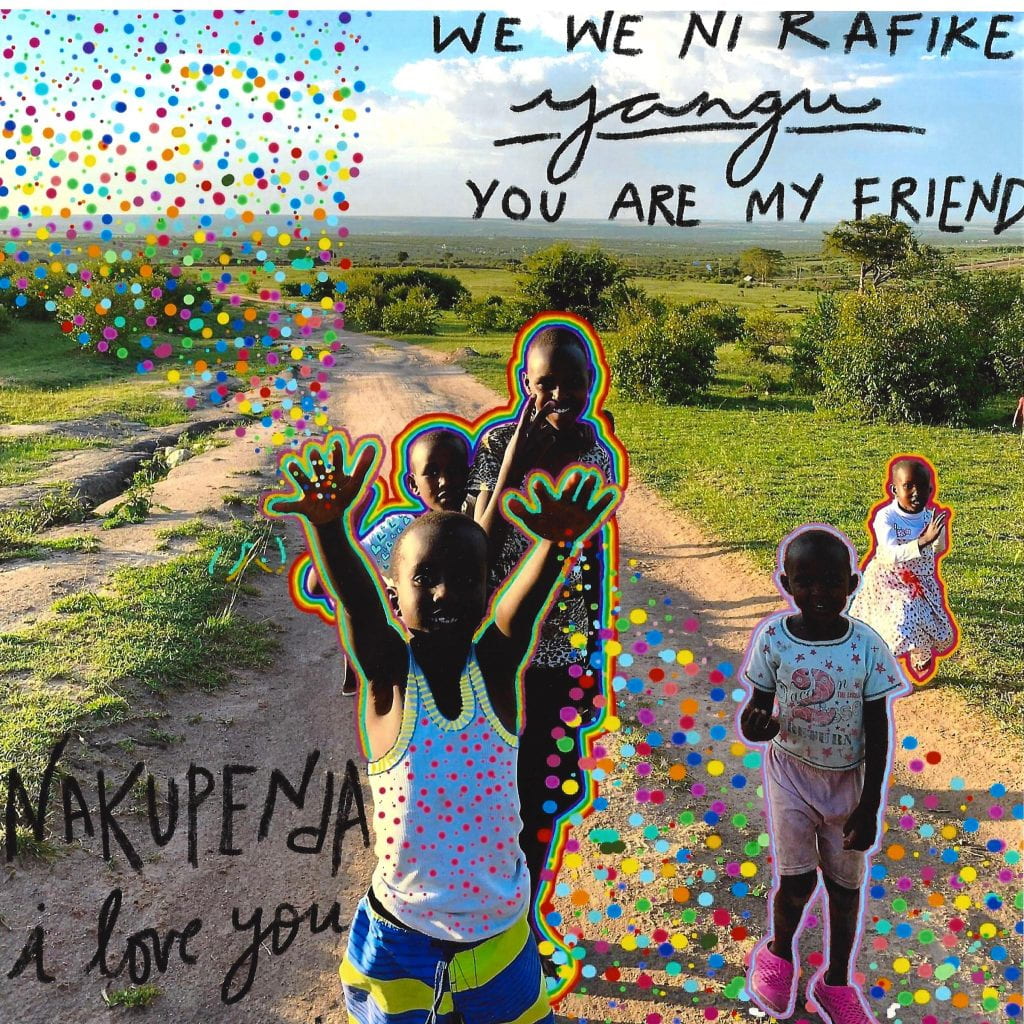

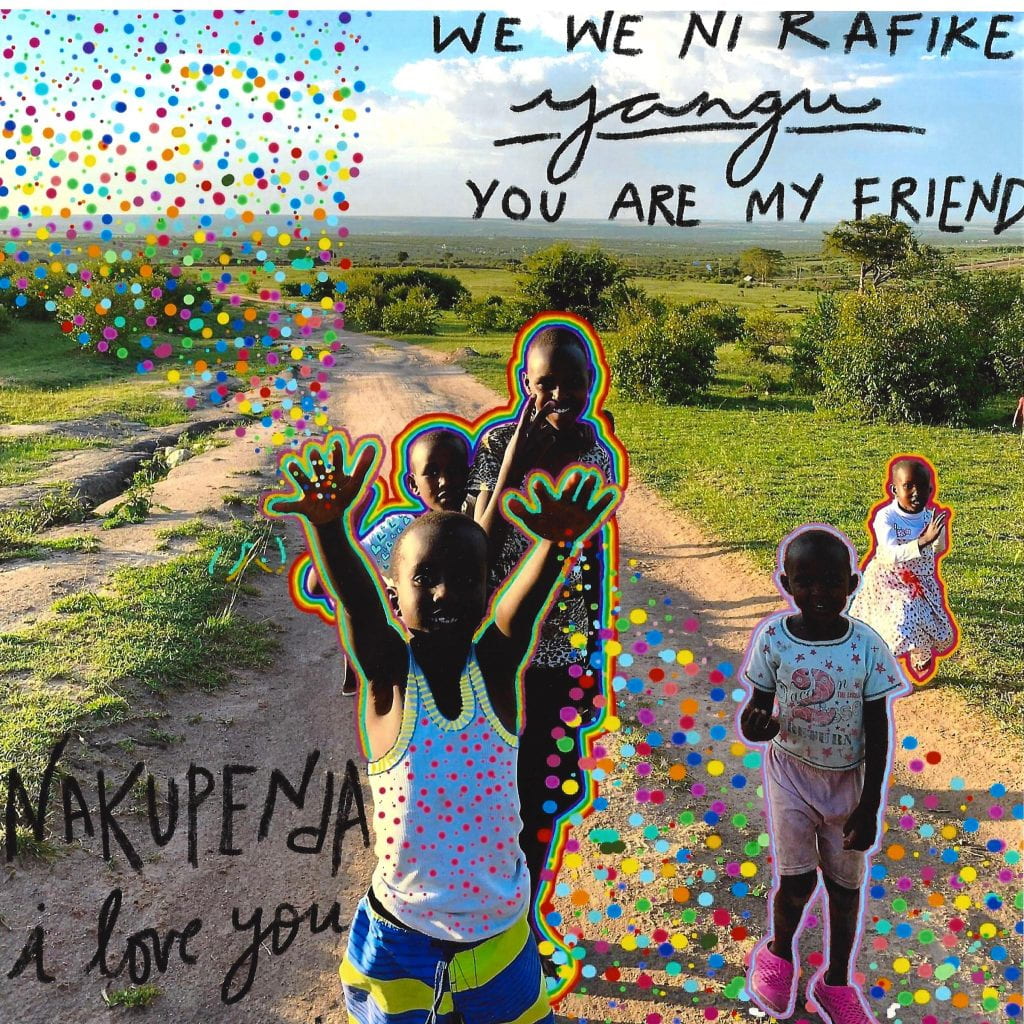

We we ni rafike yangu & Nakupenda – “You are my friend” & “I love you”

On the first afternoon of our arrival in the Maasai Mara, we asked the warriors if they could show us around the camp. There was a village below where we stayed and as we were walking down the road the children were arriving home from school. We stopped and began to talk to these bright and inquisitive children. They drew their names in the dirt, as well as an outline of Kenya with a star where they lived. They wrote out long division problems with a stick to test my “college education”. The children giggled as they posed for photos and excitedly crowded the cameras. They opened their home, their lands, and their hearts to us without hesitation.

It was important to me that there was not a white savior mentality on this trip. I personally think that not only is the idea or concept of entering a foreign country and being a “savior” detrimental to the community, but also spreads this harmful to other Westerners considering trips to Africa. Dr. Stacy Moak and Dr. Tina Reuter, the professors who led this trip, ensured that we worked collaboratively with those in the community to provide them with the resources they needed. Change in a community does not come from a group of students visiting for one week. Members of the community are the true agents for change, and to have an opportunity to learn from them is an unforgettable experience. In many depictions of non-Western countries, the people are displayed in images of despair and poverty. This fuels the white savior complex but placing pity on these countries and the utmost need for a Westernized hero. Is there despair and poverty in Kenya? Yes. Is there despair and poverty in the United States? Yes. Regardless of where we are, considering what the photos you take and share are actually depicting is a measurable action you can take. Does the photo reflect the strength of the person? Does it treat humans in the photo as entertainment only? When someone is wanting to use imagery to advocate and empower for change, is the photo reflecting the true nature of its subject, or whatever sensationalized image will get the most emotional response?

I can’t speak to all the plights of the Kenyan people, nor can I summarize everyone who lives there within a week of being there; all I know is what I observed from my week-long trip: The people I met in Kenya are smart. They are curious. They are happy. They are resilient. Maybe if others had more opportunity to engage with non-Western worlds in an accurate and authentic way some of the negative mentalities and complexes surrounding how we view the rest of the world would begin to be transformed. I was fortunate to get physical proximity to the people of Kenya and the characteristics they exhibit, and hopefully, the visuals I shared will begin to give others a sort of pseudo-proximity to the humanity in all.

Moja & Billie (Mbili) –

Moja & Billie (Mbili) –