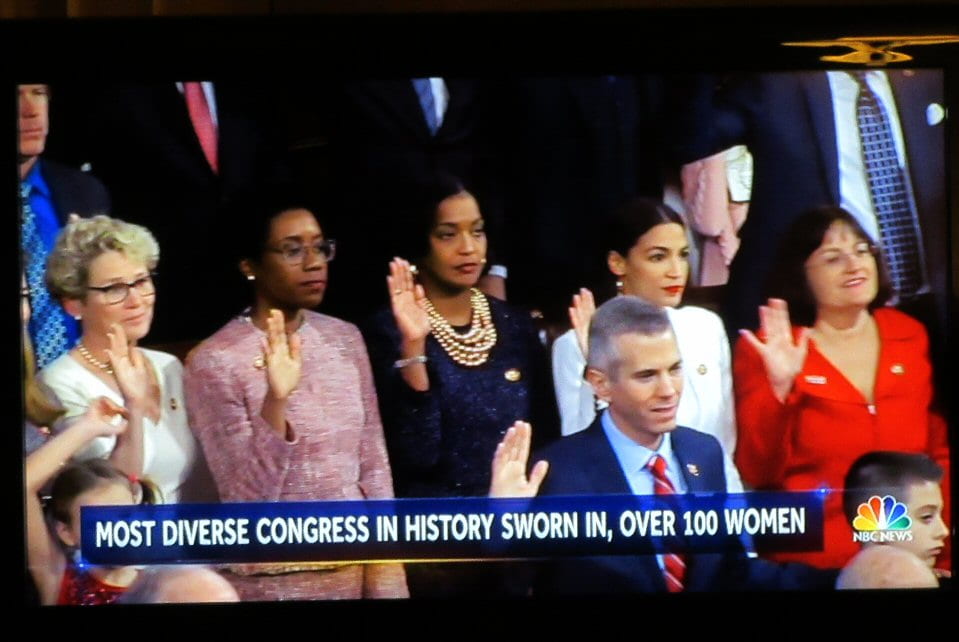

Today is International Women’s Day. This year’s theme is “Think Equal, Build Smart, Innovate for Change.” In her context statement about the theme, UN Women Executive Director Phumzile Mlambo-Ngcuka states that the changing world continues to shape the lives of people and “we have to be intentional about its use to positively impact the lives of women and girls. [The theme] puts innovation at the centre of efforts to reflect the needs and viewpoints of women and girls and to resolve barriers to public services and opportunities.” Innovation highlights the game-changers and activists willing to “accelerate progress for gender equality, encourage investment in gender-responsive social systems, and build services and infrastructure that meet the needs of women and girls.” The goal of today is to celebrate the incredible achievements of women and girls who seek to overcome their marginalized status in their communities, level the representation across various academic disciplines and professional fields and undo the cycles of intersectional injustices to bring about a more equitable world.

History

What started as a response to a women’s labor strike in New York 1909 became an international movement to honor the rights of women and to garner support for universal women’s suffrage. In 1913-14, International Women’s Day was a tactic to protest World War I as a part of the peace movement. The UN adopted 8 March as the official date in 1975 during the International Year of Women. Gender equality and the empowerment of all women and girls is Sustainable Development Goal #5 in 2015.

Celebrating some game-changers and activists

The list below is not extensive. Its purpose is to assist you in your search to discover and know what women are doing and have done around the world.

Kiara Nirghin: Won Google Science Fair for creating an orange and avocado peel mixture to fight against drought conditions around the world. She will join Secretary-General António Guterres.

Elizabeth Hausler: Founder of BuildChange.org, an organization that trains builders, homeowners, and governments to build disaster-resistant homes in nations often affected by earthquakes and typhoons.

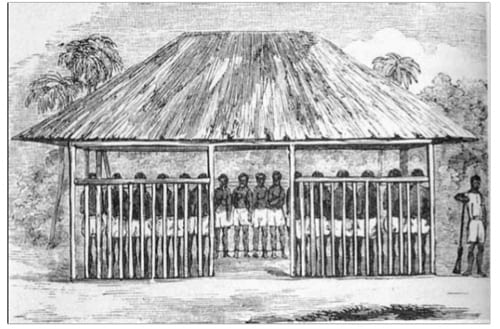

Jaha Dujureh: Founder of SafeHandsforGirls.org, an organization fighting to end child marriage and female genital mutilation (FGM).

BlackGirlsCode.com: A San Francisco based organization seeking to increase the number of girls from marginalized communities in STEM fields by 2040.

Shakhodat Teshebayeva: When the water crisis threatened her livelihood, she organized and mobilized a women’s group to advocate for a place for women at the discussion table regarding equal access to water.

Mila Rodriguez: Cultivates safe spaces for young people to use music to promote peace in Colombia.

Wangari Maathai: late Nobel Peace Prize Laureate from Kenya who initiated the GreenBeltMovement.org by planting trees for the cultivation of sustainable development and peace.

Next Einstein Forum: Continental STEM forum in Africa

Una Mulale: the only pediatric critical care doctor in Botswana who works to combine medicine and art to bring healing to the body and the soul.

The Ladypad Project

This coming week, Dr. Tina Kempin Reuter and Dr. Stacy Moak will take 12 UAB students to the Maasai Mara in Kenya. The team, in collaboration with the I See Maasai Development Initiative, will fund education on women’s health rights and provide 1500 girls with materials, including underwear and reusable pads, for menstrual hygiene management. The project was awarded a grant through Birmingham’s Independent Presbyterian Church Foundation.

Continuing the Fight

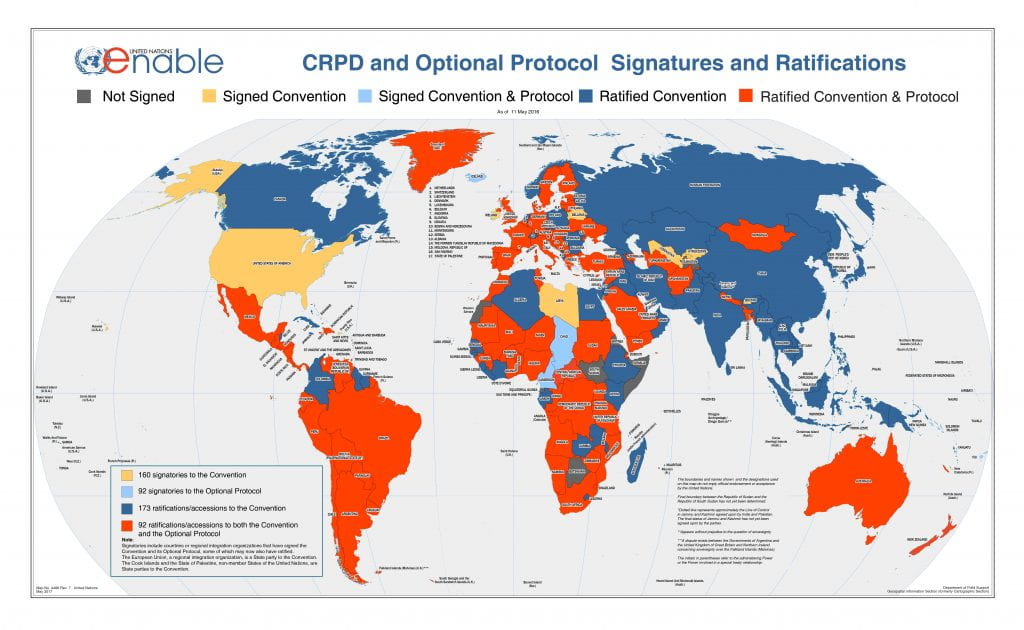

International Women’s Day is not only about celebrating the accomplishments of women and girls, but it is also about shining a light on the continuing injustices faced by more than half of the world’s population. From femicide and early marriage to FGM and sexual violence and exclusion from peace talks, gender inequity discounts the contribution of women and girls to the overall value of humanity. Kofi Annan, the late UN Secretary-General, posited that the empowerment of women proves more effective than any other tool for development. Noeleen Heyzer concludes that although there are women’s issues and rights still to be raised and respected, including those outlined in the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women, there are many that we must continue to protect. March is Women’s History Month and our contributors will write about issues that continue to impact the lives of women and girls around the world.