Disability rights is an increasingly important issue in our society. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, one in four people in this country have a disability. With such a large segment of our population facing a type of disability, it is crucial for the expansion and protection of disability rights. One way in which support for people with disabilities (PwD) can be increased is through the sharing of personal narratives of the experiences and lives of individuals with a disability. Narratives help to educate the public and prevent unintentional bias or stereotypes from causing harm to this community. Giving an individual with a disability an opportunity to open up and share their stories will help empower many of our friends, families, and neighbors and show that every single member of society matters and is appreciated.

Personal narratives are a great way to bridge the gap and inform the general population about disability issues. Oftentimes what people know about disabilities stems from limited education in schools or medical commercials. These outlets tend to focus on statistics and don’t address the issue on a personal level because most of the times they are not consulting an individual with a disability. Even though one in 4 people in this country have a disability, people lack a personal connection that allows them to fully understand the discrimination and ignorance that a person with a disability faces. In fact, it is common for individuals with a disability to have stories where people have stared at them, gawked at them, pointed at them, laughed at them, or even flat out harassed them in public. In all of these cases, PwD are not treated like normal people and are often made to feel ostracized. This disconnect needs to change and this mistreatment of people with disabilities needs to end. If people hear these stories from the viewpoint of a disabled person, then a personal connection is far easier to establish.

A personal connection between both communities is crucial. Empathy and understanding are needed to end fear and uncomfortable feelings when engaging with people with disabilities. It is important for people to realize that disabilities aren’t diseases you can catch. In fact, PwD pose no risk whatsoever to those around them. Listening to PwD talk about their conditions, lives, and how they overcome their disabilities to live a fulfilling life dispels all rumors and falsehoods about disabilities. Stereotypes and prejudice disappear when people see that disabled people are just like them and that disabilities do not define an individual. Each PwD has their own unique identity that is not affected by their disability.

To combat the lack of understanding, misinformation, and stereotypes about PwD and diminish the gap that exists between both communities. It is important to create a safe place for this community. A safe place is an environment where PwD feel comfortable enough to express themselves and share their stories without any fear of judgment or repercussions. Such an environment would make them feel normal and not different from the people around them. It is high time that disabilities were normalized and that PwD are given the same treatment as anyone else. Creating a PwD inclusive space allows the PwD community to strengthen. The benefit of this is that it lets PwD not only advocate for themselves but also to advocate for other people in their community so they might not have to go through the same prejudices.

To create this safe place for PwD it is imperative to promote representation and educate people about individuals with disabilities so that disabilities are normalized in the public eye. Increasing the population’s amount of interaction with PwD is not difficult and is much needed. The earlier this takes place, the better. If society’s youth is brought up surrounded by their peers with disabilities, it would allow both communities to learn a lot from each other. Teaching younger generations how to interact with PwD is a good place to start. Treating these lessons like any other instance where you would educate a younger person about manners and social cues can prevent a lot of uncomfortable situations for people with disabilities. It can also prevent harmful biases from growing in a young child’s mind since their exposure and prior knowledge makes them understand that individuals with disabilities are humans too.

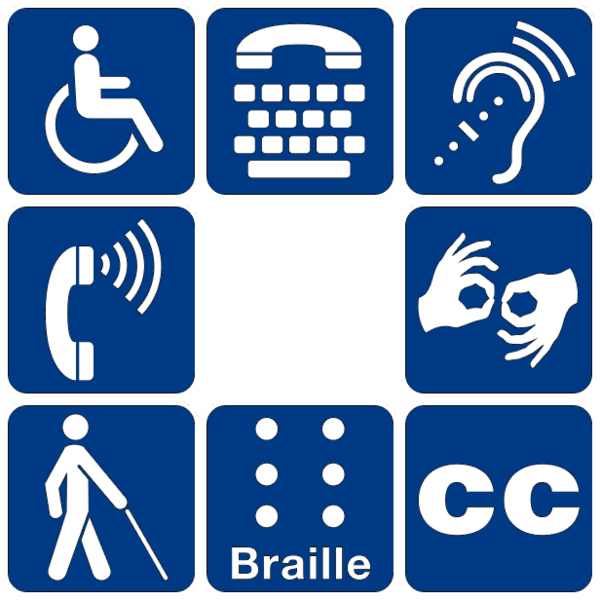

Often times, disability policies have typically been developed for people with disabilities without their direct participation. An element to creating a better environment for people with disabilities is to ensure that they are active in all sectors of the economy. It is a great thing that most public areas are now required to be accessible to PwD. The use of ramps, elevators, sloping curbs, lifts for public transportation, and other methods are required by law to ensure that PwD can navigate through their everyday lives regardless of movement impairments. However, even though these fixtures for creating a more accessible space is mandated by the law, there are many instances where there is only one wheelchair accessible table at a restaurant, or a ramp inconveniently located at the backside of an establishment. It is not only about making space accessible, it is also about how conveniently these resources are accessible to PwD. The reason that disability friendly spaces are sometimes difficult to come by is that people with disabilities are often not the ones designing these spaces. However, having a person with a disability as someone in charge or as a consultant for these issues can help the ball get rolling. So far society has expected people with disabilities to modify themselves to fit in, but having society bend the rules to accommodate people with disabilities can be beneficial to the growth of this community. Therefore, having people with disabilities in charge and active in leadership roles can spearhead this campaign.

Representation is incredibly important for people with disabilities. The marginalization and ostracism of people with disabilities severely hinder their representation in media and pop culture. People with disabilities are the largest minority group in the United States. Yet, the 2017-2018 GLAAD report (report that analyzes diversity in television) found that only 1.8% of characters have a disability making them the least represented minority group in the TV industry. Representation shows the disabled community that they are welcome and belong just as much as any other community. Representation is not only about quantity, but also about being represented accurately without perpetuating any negative stereotypes. More often than not, people with disabilities are depicted in TV shows and movies as these characters that are trying to overcome their disability. It would be more appropriate to show these characters embracing themselves and having a purpose bigger than overcoming their disability. This supports the argument for having more individuals with disabilities as writers, directors, producers, or media consultants. When someone without a disability creates media from the perspective of an individual with a disability, they struggle to paint a truthful picture. This may cause someone without a disability to make assumptions and maintain stereotypes. Having better quality and quantity of disability representation will expose the population to more realistic experiences of individuals with disabilities. This can help generate truthful interchange between communities.

A simple change in the public’s perception of disabled individuals would go a long way in accomplishing the goal of increasing rights and opportunities for PwD. If people can see past the disabilities and focus on the person, then most of the discrimination, awkward moments, and harmful stereotypes facing the disabled community can be resolved. Both communities advocating for change will allow greater access and accommodations for disabled individuals to pursue higher education, enter the workforce, and engage in public events and venues. People need to learn how to respect the rights of these individuals and help them when needed. It is essential to campaign and use powerful narratives to enact greater protections and rights to this community of people. Effectively normalizing disability by tackling these issues head-on can lead to widespread positive changes.

Keep up with the latest announcements related to the upcoming Symposium on Disability Rights by following the IHR on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram!