Note from the author: This post is the first of my four-part series on the North Korean Regime. To find the other parts, scroll down and click “View all posts by A. Price.” If the other parts are not available yet, check back in during the upcoming weeks when they will be posted.

Content Warnings: mass financial abuse, famine, malnutrition, dehumanization, classism, starvation

Imagine grocery shopping for your family, and instead of finding a variety of food choices, you find a store filled with a surplus of children’s socks, different colored hats, and beach toys even though you live nowhere near the coast. The only food you can find in the store is a few loaves of moldy bread, a small produce section filled with rotting vegetables, and a frozen section with freezer-burned packaged meat. The best you can do is buy a bag full of rotting vegetables and plant them in the ground behind your house, careful not to be caught doing so by the police. The soil you remember being rich with vitamins has turned to gray dust, and everything you plant dies before sprouting. Your family will live off the rotting leftovers from last week’s grocery trip until you can scrounge together enough scraps to make it through. You know that your neighbor has a secret garden that does moderately well, so you sneak over to offer her what’s left of your money in exchange for a few vegetables. If the police catch you exchanging goods, you and your neighbor will be charged for participating in a free market, thrown in a prison camp without a fair trial, and held for an unregulated amount of time.

The only media you’ve ever seen tells stories of a utopia; the Kim family is sent from heaven to make the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK), also known as North Korea, the most wonderful place to live. They tell you that people in other countries, like South Korea and the United States, live under terrible governments who do not care for them the way the Kim family cares for you. In the end, you have no reason not to believe them. You have never seen the conditions of other countries and any criticism of your regime has been consistently disputed throughout your entire life. The stark reality of your consistent mistreatment exists in a dichotomy with the ideals that you have been brainwashed to believe to be true.

Approximately 20 million rural North Koreans live in this reality…

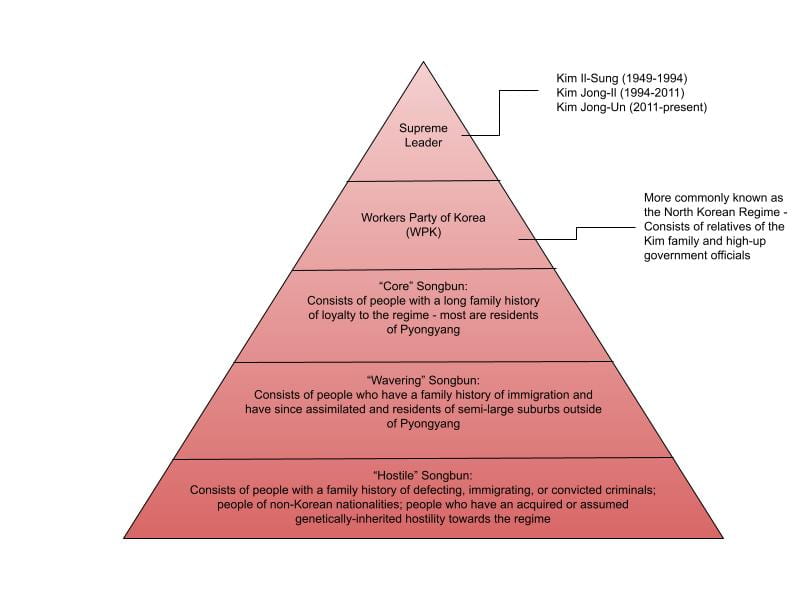

Songbun

The class system of North Korea is called Songbun. At birth, each North Korean citizen is labeled as core, wavering, or hostile based on their place of birth, status, and the national origin of their ancestors. For example, a person whose ancestors immigrated from South to North Korea will be given a low Songbun and be assumed to have genetically inherited hostility towards the government. One’s Songbun can never be changed, as it determines every aspect of one’s life including how resources will be allocated to your community and how much mobility you will have throughout the state.

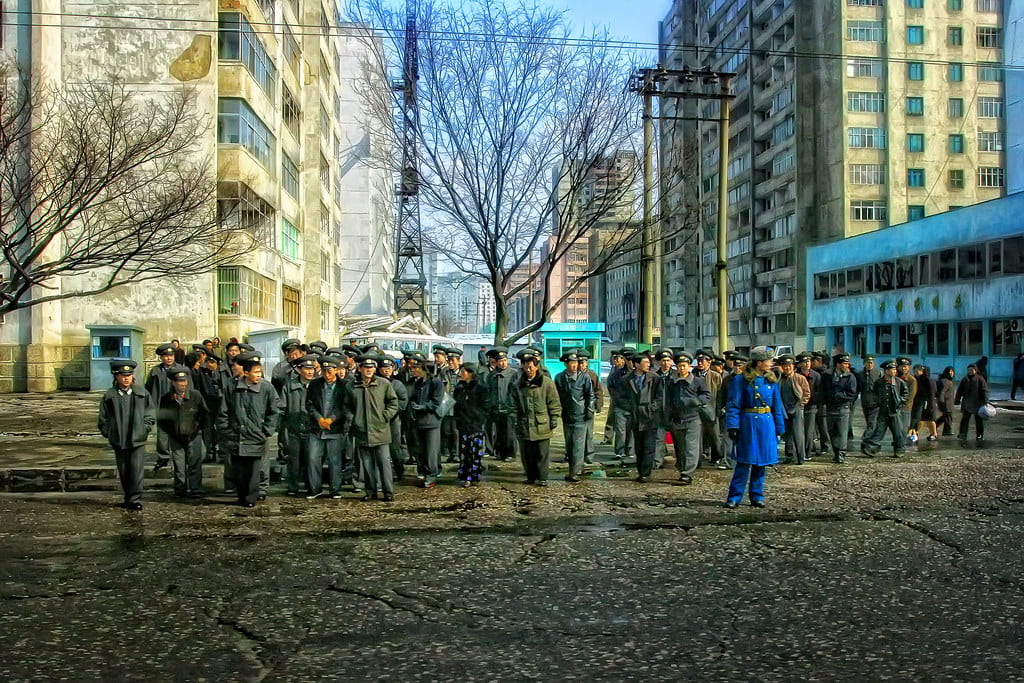

The Command Economy

The Workers Party of Korea (WPK), more commonly known as the North Korean Regime, holds tight control over the command economy and uses it to abuse all people of low Songbun, specifically those who live outside the capital, Pyongyang. Instead of ordering the production of valuable goods like food and home maintenance products for their communities, they overproduce menial things, like children’s socks and beach toys. Many do not have the mobility to go to a neighboring town for resources, and as I will expand on later, many believe that they deserve to starve if they are not entirely self-sufficient.

This economic system has the dual effect of limiting opportunities to participate in the job market. People are not allowed to sell products unless they are commanded to do so by the WPK. Because the WPK is not tasked to create job opportunities for rural people, these people have no opportunity to make money, which only exacerbates the problem of reduced resources.

The March of Suffering

The culture that encourages the idea of “suffering for the greater good” is called juche. Juche is the Korean term for the culture of self-sufficiency. It is an idea that is pushed hard into the minds of all North Koreans. Asking for help, depending on friends or family, or participating in a small-scale economy of goods with your neighbors makes you an inherently weak person because you are expected to work harder instead of “begging”. This idea is so ingrained in the minds of North Koreans that they will accept immense abuse from higher-ups at the expense of asking for help or demanding rights.

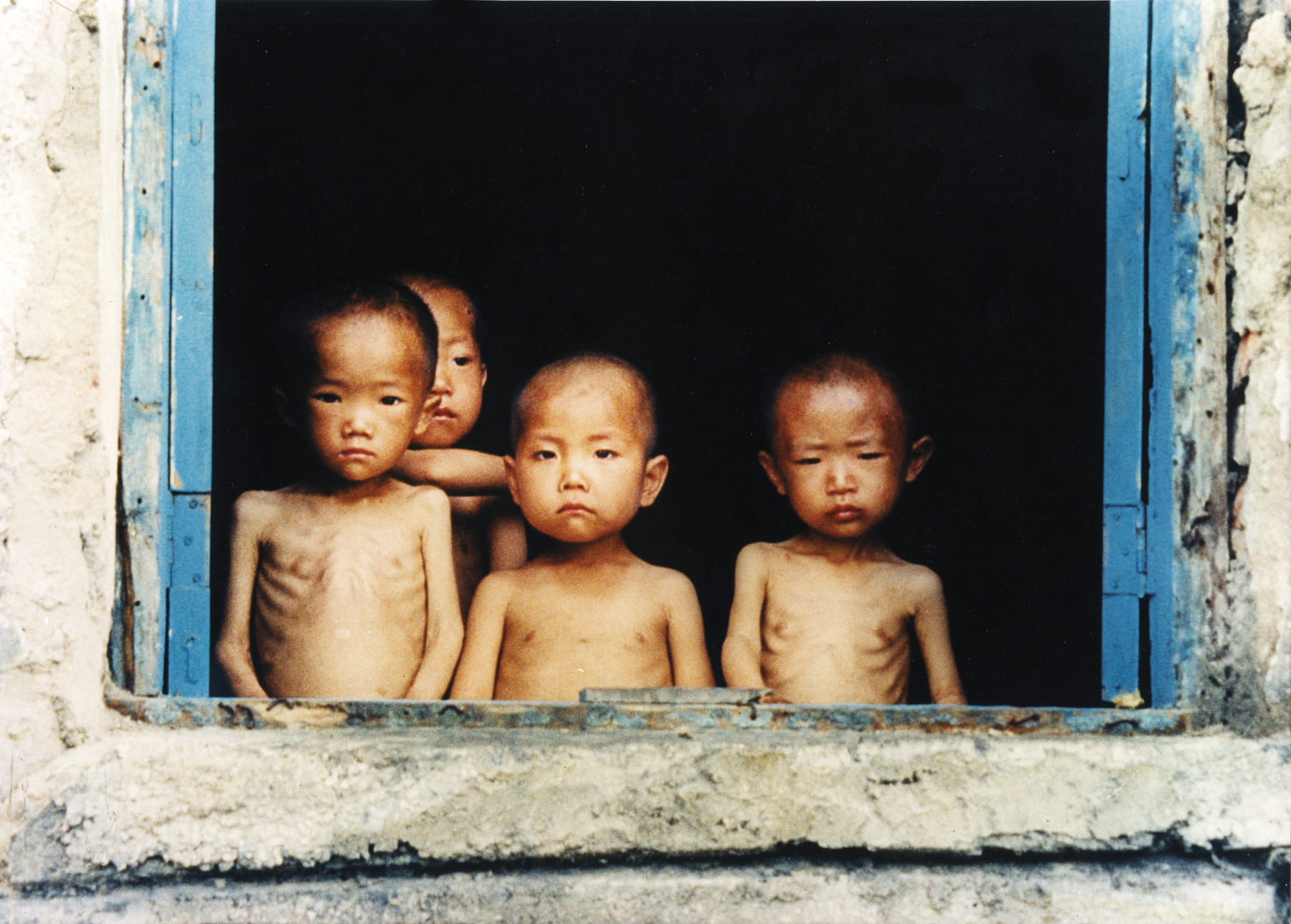

Starting in 1990, a great famine swept the nation under the rule of Kim Il-Sung. He coined the term “The March of Suffering” to refer to the famine. Using this name, he convinced those who took the hardest hit, the rural people of low Songbun, that they were doing the most honorable thing for their country by suffering in this famine. They were dying for it. Kim Il-Sung glorified their suffering by convincing them that not only did they deserve it (juche), but that their suffering was contributing to the greater good of the country. He had such control over the minds of these people that they loyally followed him straight to their graves.

Handled correctly, this famine could have lasted no longer than a year, and would not have become nearly as severe as it has. Instead, estimates from Crossing Borders suggest that between 240,000 and 3.5 million people have died in the DPRK from malnutrition since 1990.* The famine has outlived not only Kim Il-Sung but also his predecessor Kim Jong-Il.

*The reason for such a wide range of statistics is that collecting accurate data in North Korea is virtually impossible. I expand on the use of outside media control in the second part of this series titled, “How the North Korean Regime Uses Cult-Like Tactics to Maintain Power.”

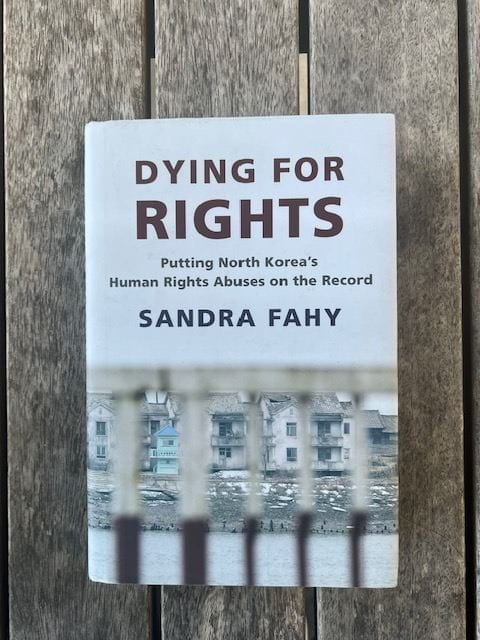

Suppose the topic of North Korea is interesting to you and you want to work towards clearing up the fog surrounding the nation. In that case, I highly recommend Dying for Rights: Putting North Korea’s Human Rights Abuses on the Record by Sandra Fahy. This book is very informative and one of the only easily accessible, comprehensive accounts of North Korean human rights. It is where I learned most of what I know about the DPRK. It set the baseline on which I built my entire comprehensive understanding of the social systems at play.

As I will expand upon in the rest of this series, it is imperative that people outside of the DPRK “clear the fog” and find ways to look into the state. One of the biggest motivators for activism is awareness. As people on the outside, some of the most valuable things we can do are spread awareness, garner activism, and bring that activism with us into our participation in the government, whether that be running for office or simply voting for people who share our concerns.

If you are not registered to vote, you can do so here: Register to vote in the upcoming midterm election today.