People living in the Appalachian region of the United States have been victims of a number of failures to protect their basic human rights since at least the nineteenth century. As a result, in nearly every measurable socioeconomic category, the Appalachian region lags behind the rest of the United States in development, or even shows signs of decline. This, in combination with their remoteness and social isolation, has led to a remarkably divided society evidenced over the last hundred or so years. Outdated and incorrect perceptions of the Appalachian people have led to antagonism and a struggle to implement democratic institutions that protect some of America’s most vulnerable populations.

The Appalachian mountains in the Eastern United States extend across thirteen states and are home to over twenty-five million people. Appalachia struggles with problems typical of rural poverty: social stratification, unemployment, lack of social services, poor education, and poorly developed infrastructure. The Appalachian region, and its perceived separateness from the rest of the Eastern and Southern United States, is especially relevant in contemporary times of remarkable social division. Healthcare disparities, income inequality, and extensive exploitation of Appalachian communities by outside corporations have all contributed to distrust and frustration among their inhabitants. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, a large number of Appalachians sold their rights to land and minerals, leading to a massive disparity in ownership and control of the land. Ninety-nine percent of the residents of Appalachia control less than half of the land — despite the area’s vast natural resources, inhabitants remain poor (Hurst).

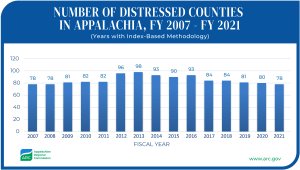

The Appalachian region has had a higher poverty rate and a higher percentage of working poor than the rest of the nation since at least the 1960s, in addition to low wages, low employment rates, and low-quality education. To address this, the Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) was established in 1965, as a joint effort of ten governors of Appalachian states seeking federal government assistance. Still, by 1999, nearly twenty-five percent of the four-hundred twenty counties in the region qualified as “distressed”, the ARC’s lowest status ranking. Fifty-seven percent of adults in central Appalachia did not graduate high school, compared to less than twenty-percent for the rest of the United States. According to ARC, thirty-three percent of Appalachians suffer from poverty and their income was twenty-three percent lower on average than the level of American per capita income. There has been some improvement, however, with levels of economic distress reaching lows not seen since before the recession in 2007 (ARC.gov).

In addition to economic inequalities, political inequalities are present in Appalachia. Racial divisions have often been stoked to divide workers and pit races against each other. During Reconstruction, the period after the American Civil War in which Southern states were radically reformed, coal corporations discouraged education and civic action, forcing workers to become indebted to company stores, live in company housing, and generally become vulnerable to their employers. Community members regularly experienced punishment as a reprisal for speaking out against their employers. In his study of culture and poverty in Appalachia, Dwight Billings suggests that this has resulted in a fatalistic attitude in the Appalachian people, based on a history of political corruption and disenfranchisement, leading to a sense of powerlessness.

The plight of the Appalachian people is deeply ingrained in me and will remain always of academic and personal interest. My own paternal kin originally settled in the Appalachian Mountains in North Carolina after arriving in America. As far as we can tell, my ancestors passed through the Cumberland Gap in the mid-eighteen-hundreds or earlier, finally homesteading in the foothills of the Appalachian Mountains on Sand Mountain, in northeast Alabama. On the other side of my family, my maternal ancestors shared many of the same challenges living as sharecroppers and later as miners in north-central Alabama. Eventually, both sides of my family came to work in blue-collar industrial jobs in mining and steel-work, industries that would become encumbered by the same failures, oppression, and corruption that were endemic in their Appalachian cousins. My great-grandfathers and my paternal grandfather were heavily involved in the labor movement in the American South and leaders of rights-protecting unions, such as the United Mine Workers of America and United Steelworkers, even as those same unions fell into disorder and ineffectiveness.

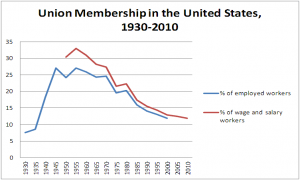

My research has indicated that one of the best ways we could better protect workers and their human rights would be to focus on the renewal of unions in the Southern and Appalachian Regions of the United States. Unions have been shown to raise wages, reduce wage inequality, and protect rights for workers. Higher rates of unionization and collective action generally tends to be an indicator for greater respect of human rights in industry. After declining membership from its peak in 1954, a once-thriving union movement had shrunk to nearly a third of its size by the turn of the 21st century.

Corresponding with this drop in membership, middle class incomes shrank accordingly. The Labor Department did report the first increase in union memberships in twenty-five years in 2007, which was also the largest increase since 1979, but it appears that this was a short-term gain in the larger scheme of things. Taking a broader look shows that from 1983, union membership has been on a steady decline.

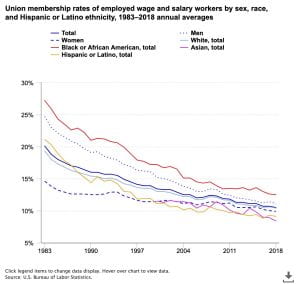

One silver lining is that there seems to be a slight turning of the tide among women and Black people, whose membership in unions is stabilizing at least, if not increasing slightly. If unions are meant to preserve and protect the rights of workers, it should inspire some optimism that some of the most vulnerable workers, BIPOC and women, are seemingly joining unions at higher rates than other demographics.

In a series of blog posts for the Institute for Human Rights, I will explore some of these challenges with which the Appalachian region are faced — workers’ rights challenges and the possibility of renewal for unions, socioeconomic disparity and the ensuing human rights failures in the region, and the political inequalities that are especially present in the region. In my next post, I will tell the story of the Battle of Blair Mountain, and describe the ways corporations have exploited workers and prevented unionization in the past. We will analyze how these barriers affect workers’ rights in some of the most vulnerable populations in America.

References:

- Hurst, Charles. (1992). Inequality in Appalachia. Social Inequality: Forms, Causes, and Consequences, 6th Edition. Pearson Education. pp 62-63.

- Speer, Jean Haskell (January 1, 2010). “Appalachian Regional Commission”. Tennessee Encyclopedia of History and Culture. Nashville: Tennessee Historical Society and University of Tennessee Press.

- Denham, Sharon. Mande, Man. Meyer, Michael. Toborg, Mary. (2004). Providing Health Education to Appalachia Populations. Holistic Nursing Practices 2{X)4:I8(6):293-3O1.

- “ARC History”. Arc.gov. Appalachian Regional Commission. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Duncan, Cynthia Mildred. (1999). Civic Life in Gray Mountain. Connection: New England’s Journal of Higher Education & Economic Development, Vol. 14, Issue 2, Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Billings, Dwight. (1974). Culture and Poverty in Appalachia: a Theoretical Discussion and Empirical Analysis. Social Forces vol. 53:2. Retrieved July 12, 2020.

- Madland, Walter, and Bunker, “As Union Membership Rates Decrease, Middle Class Incomes Shrink.”, AFL-CIO, May 24, 2013.

- Freeman, Sholnn (January 26, 2008). “Union membership up slightly in 2007; Growth was biggest in Western states; Midwest rolls shrank with job losses”. The Washington Post. p. D2