by Chadra Pittman

Trigger Warning: The language in this post will speak directly to the global violence perpetrated against women and heinous crimes which target women and girls. Specifically, sexual abuse, sexual assault, rape, and femicide/feminicide will be referenced. Please seek counseling if you are triggered by this post.

On Language: When I refer to “women,” I am including all humans who identify as women, including cis, trans, gender non-binary and intersex women. I acknowledge that some of the statistics in the article may not specify nor distinguish how women identify sexually and therefore, may predominately represent women who are cis gendered in their findings.

This blog is dedicated to the beloved daughter, sister, and mother, Connie Sue Kitzmiller. Her spirit and memory live on through her daughter and two granddaughters.

They were known as las mariposas (the butterflies), a code name for their underground resistance organization, “Movement of the Fourteenth of June.” Patria, Minerva and María Teresa Mirabal, otherwise known as The Mirabal Sisters, were passionate about the fight for justice and liberation of their people and their land in the Dominican Republic (DR), and they were vehemently opposed to the dictatorship of Rafael Trujillo. Born into an upper middle-class family in the province of Salcedo, these “powerhouse 20th-century Dominican women activists” were university-educated, career women. While Minerva was the first woman to graduate from law school in the DR, her opposition to the government resulted in her being banned from practicing. She was arrested for her political resistance, and her law degree was revoked by Trujillo. While their parents opposed the politics of Trujillo, they pleaded with their daughters not to get involved in the movement. Of the four daughters, Dede was the only one who abstained from the resistance movement (though she now upholds the memory and carries on the legacy of her sisters). The other three sisters spent many years on the front lines of the struggle, even serving time in prison with their husbands, also resistance fighters. There were some who said the Mirabal sisters did not fit the stereotypical image of revolutionaries as they were women and part of the social elite. However, the sisters challenged that paradigm, and they are lauded as “Martyrs of the Dominican Resistance,” “world symbols for women’s struggle“, and “global symbols of feminist resistance.”

According to history.com, “During the U.S. occupation of the Dominican Republic from 1916 to 1924, Rafael Trujillo joined the Constabulary Guard and was trained by U.S. Marines. His military career quickly progressed and by 1927 he was named commander in chief of the National Army.” Commander Rafael Trujillo seized control of the DR in a military coup, and in 1930, with the approval of the United States, Trujillo, or “El Jefe” (The Boss), became the dictator of the DR for the next three decades. While Trujillo was credited with advancing the DR economically by reducing its foreign debt, Trujillo also engaged in nepotism, ensuring that his family and supporters profited from the country’s economic gains.

As expected in a dictatorship, civil and political liberties in the DR began to diminish, and he named the Dominican Party the official and exclusive political party of the DR. The success of the Cuban revolution and Fidel Castro’s rise to power in January 1959 influenced many Dominicans to join the resistance movement. For ten years, the Mirabal Sisters were engaged in activism, giving voice to the many social and political injustices that plagued the people of DR.

Human Rights Violations

Beyond his unsavory and criminal business tactics, were“his heinous human rights violations.” Trujillo was responsible for the torture and murder of thousands of civilians and dissenters to his dictatorship. From the rape of women, kidnapping, torture, and intimidation tactics, to the brutal and racist massacre of 20,000 Haitians during the Parsley Massacre, Trujillo utilized the police to carry out his nefarious deeds towards the citizens who opposed his regime.

“On November 2, 1960, facing an outpouring of public sentiment against his regime, Trujillo publicly stated that he had only two problems left: the Catholic Church and the Mirabal sisters.” As Nancy P. Robinson writes, “Trujillo’s hatred for the sisters was not just political but personal: he was furious at Minerva for rejecting his sexual advances, perceiving this as an affront to the machismo that powered his authoritarian leadership.” For those who told Minerva that Trujillo was going to kill her, her response was “If they kill me, I’ll take my arms out of the grave and be stronger.”

The Murder of the Mariposas

Tragically, Minerva’s words came to fruition. Just three weeks after Trujillo’s remarks, the sisters were returning from visiting their husbands at a prison in Puerta Plata when Trujillo’s henchmen forced their car to stop alongside a mountain road. Their driver, Rufino de la Cruz was killed and then the sisters were suffocated and beaten to death. In an effort to simulate an accident, their car was plunged over a cliff. At the time of death, the sisters were between 26 and 36 years old, and had five children in all. The children were left motherless, the family was devastated, and the community was horrified by the brutality of this violent crime. The Mirabal sisters were brutally assassinated because of their identity as women and activists. The Mirabal Sisters were victims of femicide and injustice.

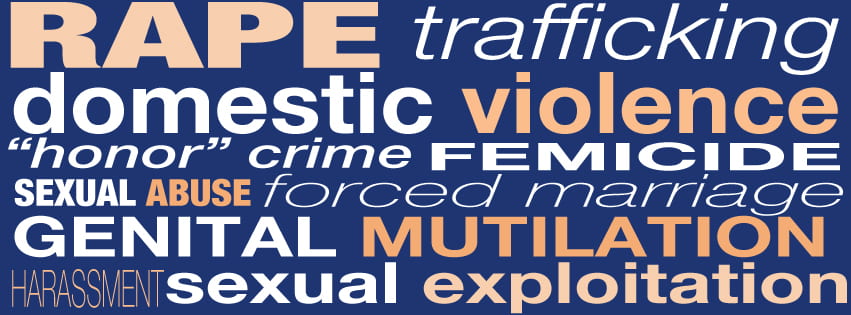

Defining Gender-based Violence and Femicide

According to the United Nations, “Gender related killings also known as femicide/feminicide are the most brutal and extreme manifestation of a continuum of violence against women and girls that takes many interconnected and overlapping forms. Defined as an intentional killing with a gender-related motivation, femicide may be driven by stereotyped gender roles, discrimination towards women and girls, unequal power relations between women and men, or harmful social norms. “Globally, an estimated 736 million women across 161 countries and areas—almost one in three—have been subjected to physical and/or sexual intimate partner violence, non-partner sexual violence, or both at least once in their life (30 per cent of women aged 15 and older).” There has been a push to categorize femicide as a hate crime as hate crimes target specific groups and femicide targets women and girls.

“From the burning of witches in the past, to the more recent widespread custom of female infanticide in many societies, to the killing of women for “honor,” we realize that femicide has been going on a long time. But since it involves mere females, there was no name for it before the term femicide was coined.” (Defining Femicide by Diana E. H. Russell, Ph.D. Introductory speech presented to the United Nations Symposium on Femicide on 11/26/2012)

Igniting a Flame for Feminists Around the World

While Trujillo hoped to permanently silence the Mirabal Sisters, instead their murder ignited a flame amongst feminists and feminist-minded individuals who are committed to protecting the lives of girls and women around the world.

After their deaths, the “Mirabals instantly became martyrs to the revolutionary cause, helping solidify resistance to Trujillo both at home and abroad.” “Killing women…was just beyond what people could stomach, and that catalyzed a lot of people to become more active in the movement,” says Elizabeth Manley, an associate professor of history at Xavier University of Louisiana.

Many grassroot organizations took it upon themselves to remember the contributions of the Mirabal Sisters. In 1981, in honor of the Mirabal Sisters, the Feminist Encounter of Latin American and the Caribbean in Colombia designated November 25th as the Day for Non-Violence Against Women.

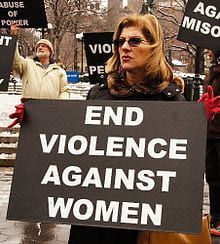

In 1993, the United Nations General Assembly adopted Resolution 48/104 for the Elimination of Violence Against Women, which defines this type of violence as “any act of gender-based violence that results in, or is likely to result in, physical, sexual, or psychological harm or suffering to women, including threats of such acts, coercion or arbitrary deprivation of liberty, whether occurring in public or in private life.” Consequently, to solidify this decision, in 1999 the General Assembly proclaimed 25 November as the International Day for the Elimination of Violence Against Women in honor of the Mirabal Sisters.

How You Can Help End Femicide and Violence Against Women and Girls

However, we know from the wise words of poet and activist Audre Lorde that “Your silence will not protect you” and we cannot afford to be silent while women and girls are dying at astounding rates at the hands of oppressive systems.

You can add your voice to the conversation and help to break the silence around the violence against women and girls. The United Nations has created initiatives to help you get involved. You could join “The 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence,” which is an annual international campaign that begins on 25 November, the International Day for the Elimination of Violence against Women, and runs until 10 December, Human Rights Day.”

The campaign was started by activists at the inauguration of the Women’s Global Leadership Institute in 1991. Annually, the Center for Women’s Global Leadership coordinates this campaign, which calls upon individuals and organizations around the world to develop strategies for the prevention and elimination of violence against women and girls.” In 2008, the United Nations Secretary-General launched the campaign UNiTE by 2030 to End Violence against Women. The theme of this year’s campaign is “UNITE! Activism to end violence against women and girls.” See the concept note here.

In Remembrance of the Mirabal Sisters

What we know is that “No country can expect to succeed in today’s globalized world by marginalizing half their population. You can’t compete with the world with only half of your people.” The Mirabal Sisters are a harsh reminder of the struggle women face globally, just trying to live their lives and speak about the issues that they face.

Their remaining sister, Dede Mirabal worked tirelessly to ensure that her sisters’ legacy would forever be etched in stone. Not only did she raise her deceased sisters’ children, she managed La Casa Museo Hermanas Mirabal / The Mirabal Sisters House Museum to keep the memory of her sisters legacy alive.

In the legacy of her mother, Minerva’s daughter, Minou Tavárez Mirabal, became a congressional representative and vice foreign minister, while Dedé’s son Jaime David Fernández Mirabal served as vice president of the Dominican Republic (1996-2000). She founded the Mirabal Sister Foundation.

The museum holds the precious artifacts from their life, even sacred memorabilia from the accident. On the 40th anniversary of their assassination, November 25, 2000, the sister’s remains were moved to the grave on the museum grounds.

The Face of Fearlessness

In the words of Julia Álvarez, author of In the Time of the Butterflies, the key to explaining why the story of the Mirabal is so emblematic is that they put a human face on the tragedy generated by a violent regime that did not accept dissent.

Now the faces of the Mirabal Sisters are known globally as the symbol of feminist resistance. They appear on the currency in the DR.

Gender violence and femicide are global problems. According to CNN, “More than 100 women have been murdered in Italy so far this year, with almost half of them killed by their intimate partner or ex-partner, the Italian police said. In Latin America, gender-based violence has come to be described as a “pandemic”, because between a quarter and a half of women suffer from domestic violence. According to the United Nations, violence against women in their own homes is the leading cause of injuries suffered by women between the ages of fifteen and forty-four.

The fight to end violence against women is ongoing, and this is not merely a woman’s issue, it’s not just a woman’s fight, nor a feminist issue, nor an issue only in certain parts of the world. Violence against women is pervasive around the world and we must do something about it.

So, start where you are, use your voice, talk to friends and family members about how we can make the world safer for women and girls. Use your talents to bring awareness to the crisis of violence against women. Join an organization, write a letter to a politician or volunteer or lend support to an organization which advocates for women and girls. Here are a few organizations across the globe working to end the violence against women.