I did not enter the world of juvenile justice reform through textbooks, research questions, or curiosity about public policy. I entered it through a child. A girl I first met when she was just fourteen years old, wide-eyed, quiet, and already carrying a lifetime of burdens on her small frame. I was assigned as her CASA (Court Appointed Special Advocate) at a time when her life was marked by instability, poverty, and trauma. She was living in conditions most adults would find impossible, yet she still greeted me each week with a hesitant smile, a mix of hope and uncertainty in her eyes. Her resilience was unmistakable, even if she didn’t yet recognize it in herself.

Over the years, I watched her survive circumstances that would flatten most adults. She moved between unsafe living situations, often unsure where she would sleep or whether she would eat. She navigated school while juggling the chaos around her. She experienced loss, betrayal, and instability. And yet she showed up. She tried. She hoped. She fought to stay afloat.

Nothing in those early years prepared me for what would come next.

At sixteen, through a series of events, she was just present when a crime occurred. One she did not commit, did not plan, and did not anticipate. But in Alabama, presence is enough to catapult a child into the adult criminal system. Under Alabama’s automatic transfer statute, Ala. Code § 12-15-203, youth charged with certain offenses are moved to adult court entirely by default, without judicial evaluation and without any meaningful consideration of developmental maturity, trauma history, or the child’s actual involvement.

The law did not acknowledge her age, her vulnerability, her role in the event, or her long history of surviving poverty, abuse, and instability. It simply swept her into the adult system as if she were fully responsible for the incident and for her own survival. Overnight, she went from being a child in need of care to being treated as an adult offender. She was taken to an adult county jail, where her new reality consisted of four concrete walls, metal doors, and the unrelenting loneliness that comes from being a minor in a facility designed for grown men.

Because the Prison Rape Elimination Act (PREA) requires strict “sight and sound separation” between minors and adults, and because most Alabama jails have no youth-specific housing units, she was placed into what the facility calls “protective custody.” In reality, this translated into solitary confinement. She spends nearly every hour of every day alone. No peers. No programming. No classroom. No sunlight. No meaningful human contact.

Not for days. Not for weeks. But for over an entire year.

Even now, writing those words feels unreal. A child, my former CASA child, has spent more than a year in near total isolation because Alabama does not have the infrastructure to house minors safely in adult jails. And it was this experience – witnessing her slow unraveling under the weight of isolation – that pushed me into research and now advocacy.

But the research came after the heartbreak.

She was the beginning, and she remains the reason.

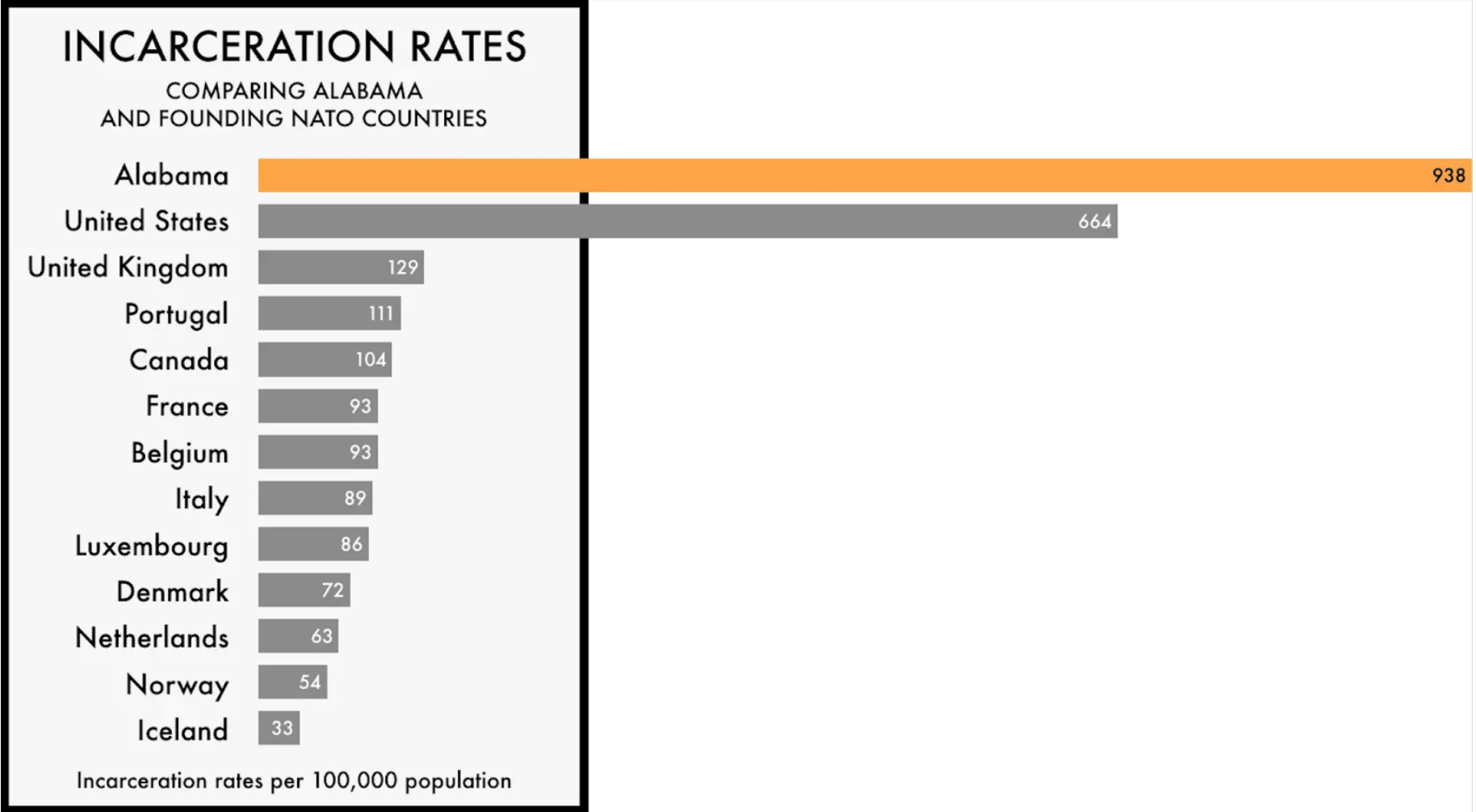

Understanding the System That Failed Her

When I began researching how a child like her could be locked in an adult jail for over a year, the data was overwhelming. In 2023 alone, an estimated 2,513 youth under age eighteen were held in adult jails and prisons in the United States, according to The Sentencing Project. Alabama is not an outlier — it is fully participating in this national trend of treating children as adults based on the offense they are charged with, rather than who they are developmentally.

The more I learned about solitary confinement, the more horrified I became.

And yet none of it surprised me, not after watching what it is doing to her.

Human Rights Watch reports that youth held in solitary confinement are 19 times more likely to attempt suicide than their peers in general populations. The United Nations Mandela Rules explicitly prohibit solitary confinement for anyone under eighteen, identifying it as a form of torture. The ACLU has documented the widespread use of isolation for youth in jails due to Prison Rape Elimination Act compliance limitations. And reports from the Prison Policy Initiative and the Equal Justice Initiative show that children in adult facilities face elevated risks of physical assault, sexual violence, psychological decline, and self-harm.

Developmental science aligns with these findings. Decades of work by scholars such as Laurence Steinberg show that adolescent brains are not fully developed — especially the regions governing impulse control, long-term planning, and risk assessment — but are exceptionally responsive to rehabilitation and growth.

Yet Alabama’s transfer laws ignore this entire body of scientific knowledge.

Even more troubling, youth transferred to adult court are 34% more likely to reoffend than youth who remain in the juvenile system. Adult criminal processing actively harms public safety.

Meanwhile, evidence-based juvenile programs, such as family therapy, restorative justice practices, and community-centered interventions, can reduce recidivism by up to 40%.

Everything we know about youth development suggests that rehabilitation, not punishment, protects communities.

Everything we know about juvenile justice suggests that children should never be housed in adult jails.

Everything we know about solitary confinement suggests that no human, let alone a child, should endure it.

And yet here she was, enduring it.

What Isolation Does to a Child

It is one thing to read the research. It is another to watch a child absorb its consequences.

When I visit her, she tries to be brave. She sees me on the video monitor and forces herself to smile, though the strain shows in her eyes. She tells me about the silence in the jail at night, the way it wraps around her like a heavy blanket. She talks about missing school — math class, of all things — and how she used to dream about graduating. She describes the fear, the uncertainty, the way days blend into each other until she loses track of time entirely.

She has asked me more than once if anyone remembers she is only seventeen.

She wonders whether her life outside those walls still exists.

She apologizes for crying — apologizes for being scared, as if fear is a defect rather than a reasonable response to months of isolation.

Watching her navigate the psychological toll of solitary confinement is one of the most difficult experiences I have had as an advocate. The changes have been slow, subtle, and painful: her posture tenser, her voice quieter, her expressions more guarded, her hope more fragile.

Children are resilient, but resilience has limits.

Solitary confinement breaks adults.

What it does to children is indescribable.

Why Alabama Must Reform Its Juvenile Transfer Laws

The more I researched, the more I understood that her story is not an exception; it is a predictable outcome of Alabama’s laws.

Ending this harm requires several critical reforms:

A child’s fate should not be decided by statute alone. Judges must be empowered to consider the full context — trauma history, level of involvement, mental health, maturity, and the circumstances of the offense.

Other states have already taken this step. Alabama must follow.

Solitary confinement is not a protective measure; it is a human rights violation.

The science is clear: youth rehabilitation supports public safety far more effectively than punishment.

- Increase statewide transparency.

Alabama must track how many minors are transferred, how they are housed, and how long they remain in adult facilities. Without data, there can be no accountability.

She Deserves Justice

I am writing a policy brief because of her.

I studied this policy landscape because of her.

I advocate for systemic change because of her.

Her story is woven into every sentence of my research, every recommendation I’ve made, every argument I’ve formed. She is the reason I cannot walk away from this fight, not when I’ve witnessed what the system does to the children most in need of protection.

She deserves safety.

She deserves support.

She deserves a justice system that recognizes her humanity.

And she is not alone. There are countless children in Alabama — many living in poverty, many from marginalized communities, many without stable adult support — who are forced into adult systems that were never designed for them.

Their stories matter.

Their lives matter.

And the system must change.

What You Can Do

If you believe that children deserve dignity, fairness, and protection, here are ways to support change:

- Support organizations working to reform youth justice in Alabama:

Equal Justice Initiative, Alabama Appleseed, ACLU of Alabama, or me — I can use all the help I can get. - Share this story to help build awareness.

- Contact state legislators and demand an end to automatic transfer and juvenile solitary confinement.

- Become a CASA and advocate for children whose voices are often ignored.

- Vote in local elections, especially for district attorneys, sheriffs, and judges — leaders whose decisions directly impact youth.

Conclusion: Children Are Not Adults—Alabama’s Laws Must Reflect This Truth

The science is clear, the research is clear, and the human impact is undeniable.

Children are developmentally different. Children are vulnerable. And, in my opinion, children deserve grace, understanding, and second chances.

When we place children in adult jails, when we isolate them for months, when we treat them as if they are beyond repair, we do more than violate their rights—we violate our own values as a society.

The 17-year-old girl I have advocated for over the past three years is a reminder of what is at stake. She is not a statistic. She is not a file number. She is a child — a child whose life, dignity, and future must matter as much as any adult’s.

She is the beginning of my story in this work, and she remains at its heart.

Her experience makes it impossible to ignore the urgency of reform.

And her resilience makes it impossible to lose hope.

Alabama can do better.

Alabama must do better.

And children like her are counting on us to make sure it happens.