by Jordan Price

One day, in the cafeteria of my small-town Alabama high school, my friend asked if I could sneak some extra snacks from the cafeteria as I went through the line, “Anything that I can put in my backpack for later.” I wondered why her question was asked so defeatedly but brushed it off as her just wanting some extra Rice Krispies treats. So I hid an extra snack in my pocket and grabbed a banana that I knew I wasn’t going to eat. As we sat down, she reached deep into her pockets and pulled out packs of carrots, an orange juice, two Rice Krispies treats, and an apple, quickly shoving it all in her backpack. I handed her what I had gotten and I didn’t ask any questions. This went on for the rest of the semester and it gradually became clearer that her love for Rice Krispies was not the driving force. Her mom had lost her job, and she had suddenly been hit with something that over 16% of Alabamians are facing: poverty.

In this article, I will lay out some aspects of Alabama’s society based on my research that may correlate to the economic disparity of the state.

Cultural Emphasis on the Free Market

Because of the biodiversity of the state and the emphasis on agriculture, many people have found success and stability in small-scale agricultural labor. When the main means of production in a community are small, family-owned-and-operated farms, most people in society have access to the means of production. Small farmers tend to pay their workers well and keep prices fair in order to compete with the many other small farms. Customers are willing to pay a fair price for the products because they trust that it is good quality due to the competition. This is how many communities in rural Alabama have historically operated, and it has fostered a strong sense of hospitality and community. This research from Auburn University in 1987 shows the cultural perception of farming and agriculture in Alabama at that time. Many people supported small family farms over larger, more industrialized farms. Many of these small farms were focused on manual, hands-on labor, wherein the employees worked closely with the means of production and saw the outcomes of their labor. This is why many people in the South hold onto values of a completely free market, with little regulations on employment, wages, and worker protections. When I mention the “shift in the industry,” I am referring to the shift from hands-on labor working directly with the Earth’s resources to more industrialized factory work and white-collar office jobs.

When the means of production become larger and farther removed from the laborers, this type of economic setup becomes an issue. The shift in industries in which Alabamians make money has privatized the means of production and reduced competition. People now are more likely to work indoors in offices, factories, and businesses, far removed from the means of production of the goods and services that they facilitate. This shift has led to many of the problems of an industrialized unregulated system to show themselves in the economic struggles of Alabamians. Employers are farther removed from their employees, meaning they are less likely to directly see all of the work being done by them. Also, under an industrialized free market, salary and wages are often set by huge company employers with little to no competition. Many people must accept these lower wages or be unemployed, making no wages. This is not to say that the free market is necessarily bad. In many ways, Alabama still relies on small businesses and agriculture. There are many ways in which the free market is fundamental to the rights we enjoy, but when a market like this gets into the hands of greedy employers with little regulations on the minimum wage and maximum workload they can give to their employees, it can be used to contribute to the economic struggles of the working class.

In Alabama, many people have the attitude that if they earn their money or belongings through work, then they deserve to hoard all of the benefits of it. The “bootstraps” view of work is heavily valued in Southern culture, which has its benefits, but ultimately fails to bring fair wages and labor conditions to the middle class post-industrialization. By the “bootstraps” view of work, I am referring to the saying that one can or should “pull themselves up by the bootstraps” when they are of lower economic class. This promotes the idea that working hard is the best way to move up in one’s socioeconomic class; however, people can be of lower economic class for a multitude of reasons, not limited to merely work ethic. This view of work rarely has the intended effect in industrialized fields. It also often excludes people with disabilities whose work opportunities are limited. Watch this Tedx Talk, where Antonio Valdés explains the logistical issues with this view and the statistics surrounding the issue. Additionally, in a strictly free-market worldview, it is often hard to justify social welfare programs, since funding for them must come from the hard-earned tax dollars of people who claim that they deserve their money, and go to people who they claim do not. Although this view does encourage people to work hard and pull their own weight in society, this system can often be manipulated to benefit a few people while pushing a large portion of the population underneath the poverty line.

Education

Another factor that is affecting the wealth of Alabamians is the education system. Alabama consistently ranks in the bottom half – mostly in the bottom 10 – of states in every area regarding education. This article puts some numbers to these statistics. There is no doubt that education correlates to economic mobility, and the education that Alabama students are receiving does not prepare them to compete in a national – much less international – job market. With the industrialization of the workforce, it is important that Alabama puts more resources into improving the quality of our education system if we want to grow economically.

During my research, I came across an article titled Alabama’s Education System was Designed to Preserve White Supremacy – I Should Know. It explains the history of the education system of Alabama and how – rather than designing schools for students to flourish through knowledge – the designers of the system were preoccupied trying to push a white supremacist political agenda. Effects of this can still be found in Alabama’s K-12 education system today, making Alabama school history and social studies curriculum a battleground of political ideologies rather than a place where children can gain a better understanding of their society. I highly recommend giving this article a read, as it was incredibly informative and helpful in my understanding of the pitfalls of the education system in which I was raised.

Slavery, Segregation, and Civil Rights

For many of its first decades, Alabama’s economy was fully held up by unpaid enslaved Black laborers. The soil in this region was the perfect conditions for cotton to be grown, so cotton, along with tobacco, were the main crops that were produced by these laborers. Once the Emancipation Proclamation was carried out in Alabama, the economy took a big hit. Rather than blaming themselves for not working “labor wages” into their finances, plantation owners blamed the formerly enslaved people for not working for free anymore. Slavery grounded our state’s history directly into the soil of race-based hatred, prejudice, and power imbalances from which we have never recovered. Segregation immediately followed emancipation and lasted for 91 years. Following this, Alabama was a significant site for the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 60s. In Selma, an event called Bloody Sunday occurred when a group of police officers used whips, clubs, and tear gas to attack protesters. In Montgomery, Rosa Parks notably refused to give up her seat to a white man, for which she was arrested. In Birmingham, Martin Luther King Jr. wrote, “Letter from Birmingham Jail,” one of the most famous pieces of writing from this movement. Still today, Alabama is one of the most socially segregated states in the United States.

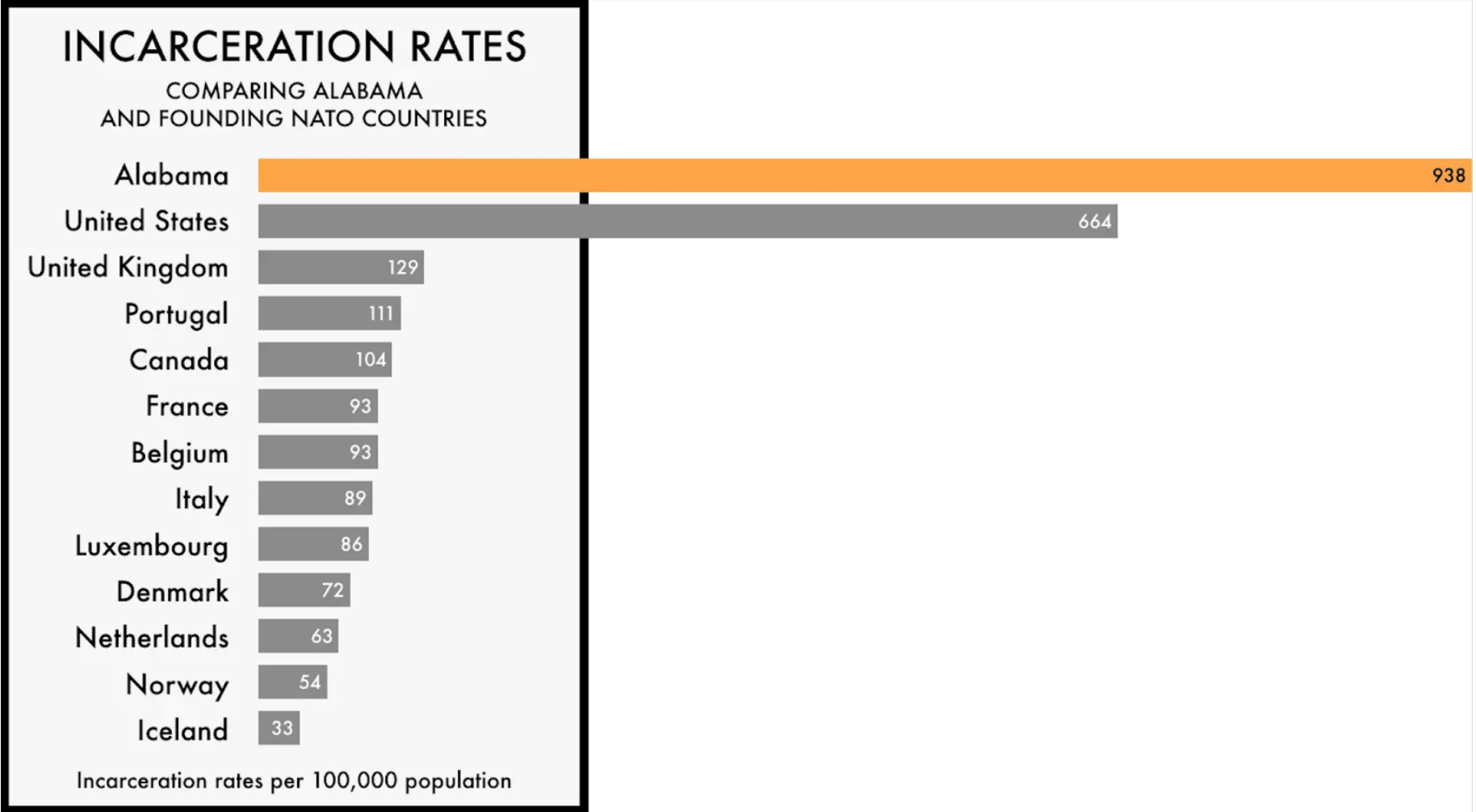

It is unsurprising that a state so steeped in racism would have such a large percentage of people in poverty. When entire groups of people live in an area but cannot work certain jobs, access an equal education, earn equal wages, or make big purchases, the entire area suffers. Economies are reliant on the ability of people to participate in them, which is the reasoning behind stimulus checks. If people don’t, or can’t, make or spend money, a free-market economy will not be strong. Not only are people of color in Alabama denied from higher-paying jobs at a much higher rate, but when they do get these jobs, they are often paid significantly less than their white counterparts. This economic inequality leaves entire communities impoverished, more likely to find themselves without a house, and more likely to commit petty crimes for survival. This creates a harsh cycle of poverty, imprisonment, and stereotyping that is incredibly difficult to escape.

Mass Incarceration

All it takes is a quick search on the Institute for Human Rights Blog to see just how many posts have been written about Alabama’s prison system. Anybody unaware of the prison crisis would think that we are beating a dead horse. They would be shocked to hear about the horrors occurring in prisons right down the road from where many of these posts were written. Maybe then, they would understand why we write so much. Because of the wealth of information on this topic, I will link a few articles written by my colleague Kala Bhattar here if you would like to learn more:

The Ongoing Alabama Prison Crisis: A History

The Ongoing Alabama Prison Crisis: From the Past to the Present

It is not a stretch to link mass incarceration to poverty. Recidivism rates (the rate at which people who have spent time in prison return to prison) are high in Alabama. Roughly 29% of people released from prison re-offend within the first three years. The Alabama government seems to attribute this statistic to these people being morally depraved, that they are just “bad people” (whatever that means) rather than to the fact that their needs are not being provided for. The classic example of the link between poverty and crime is a parent stealing bread to feed their family, when the only other option is to go hungry. Technically, stealing is a crime, but most people would agree that the parent who steals bread for their kids should not be punished as harshly as someone who steals for other, more selfish reasons. Of course, poverty does not totally excuse or account for all crime, but there is no doubt that necessity mitigates moral culpability.

This is not an extensive list of reasons why Alabamians are having the amount of economic struggles that they are having. Some others include: political polarization, excessive legal fines and fees, the fentanyl and opioid crisis, and the social disenfranchisement of pretty much every minoritized group. As an Alabamian, it is incredibly upsetting to see my state fall short in so many ways. It often feels like there is not much to be proud of, but it is important to remember that pride in one’s homeland does not mean blindly defending everything about the state. Pride in one’s homeland comes from genuinely caring for the communities that live here, criticizing the government when warranted, and guiding the culture to a more harmonious place. And caring, criticizing, and guiding is what we will do until our state sees better days.