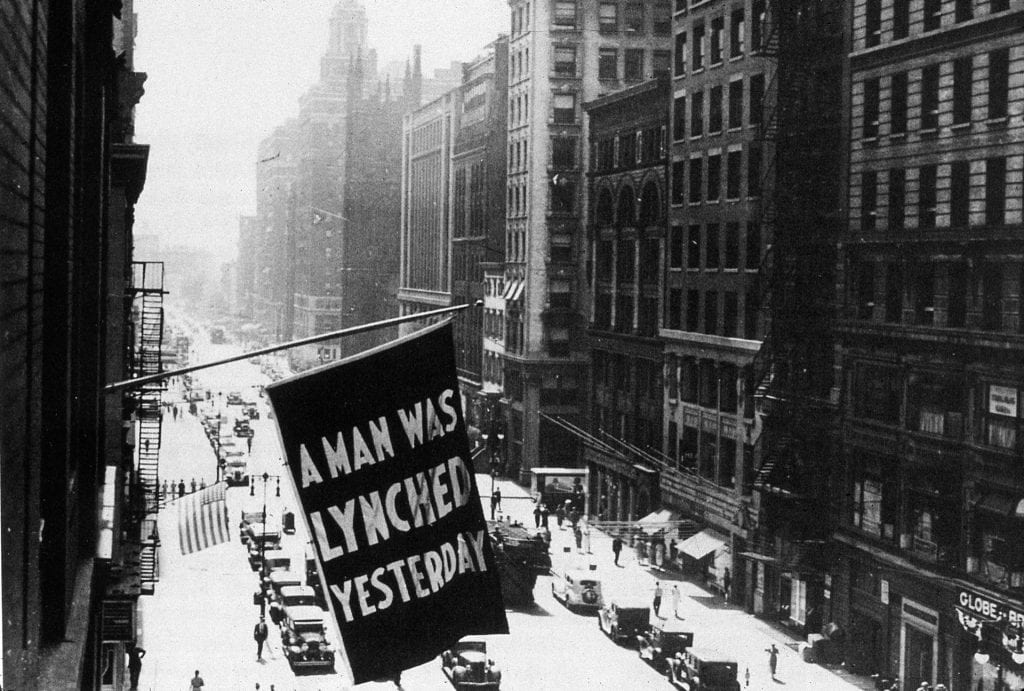

For so long, the stories of lynching victims were, as E. Stanley Richardson wrote in his poem “Century Oak: A Conversation with a Tree”, in the blind spot of America’s memory. From 1880 – 1940, the country saw a peak in racial terror. Although black communities were terrorized before and after this period, the surge started after the 13th Amendment actualized African Americans’ freedom and lasted till about World War II. White Americans lynched black men, women, and children to reestablish racial order.

“Lynching was an extrajudicial act of racial terrorism that involved killing Blacks by hanging, burning, mutilation, and other brutal assaults at the hands of white mobs (3+ people) with impunity and no fear of legal recourse. More than simply terrorizing the victim, lynching’s purpose was to send a message to the Black community at large.” (Jefferson County Memorial Project)

It was a means to violently reestablish racial order once African Americans’ freedom was recognized in the passing of the 13th Amendment to the United States’ Constitution in 1865. Black men, women, and children were lynched for many reasons. A lynching could have been triggered by something as arbitrary as a Black man holding eye contact with a white man while being reprimanded or an actual crime. Most often, a claim of sexual contact between a Black man and a white woman is what spurred a lynch mob into action. The, often unfounded, claims ranged from actual sexual assault to merely whistling at a woman. The trope of the dangerous, hypersexual Black man and the pure, delicate white woman played a huge role during this time and still affects how members of these groups are portrayed today.

Nevertheless, the unlawful punishment that the white mobs felt justified to administer was ruthless and inhumane. Even though lynching can be seen as a conflict on an interpersonal level, the effects of these acts of terror go beyond the interpersonal level. The effects of the lynching are long-lasting and have altered the way that communities function. Racial terror contributed to the Great Migration between 1916 and 1970. Almost 6 million African Americans moved out of the rural Southern United States to the more urban West, Midwest, and Northeast to find economic opportunity and flee racial terror. Those that directly experienced the effects of racial terror passed down the fear to generations, as former lynching spots that have been paved or built over still bring the same amount of terror.

In 2018, Equal Justice Initiative (EJI), a non-profit organization in Montgomery, Alabama, committed to ending mass incarceration and inhumane or excessive punishment by providing legal representation, attempted to help the county address our collective memory of lynching.

The organization says that their National Memorial for Peace and Justice “provides a sacred space for truth-telling and reflection about racial terrorism and its legacy.” The beginning of the memorial includes large hanging iron columns, symbolic of the hanging bodies that were lynched. EJI’s staff scoured national newspapers to document thousands of racial terror lynchings. At the memorial, every iron column is designated for a United States county, and the names and dates of the individuals lynched in that county are listed below.

Towards the end of the memorial, visitors can find duplicates of each of the columns lying on the ground on the trail to the exit. The organization’s Community Remembrance Project is a tool for communities around the country to engage in the work and learn about this history. The intention is that each county will prepare by educating themselves about racial terror and ultimately memorialize the victims from their community by placing the duplicate column in the county.

The Elmore Bolling Initiative, a non-profit named in honor of a prominent black farmer and philanthropist lynched in 1947 in Lowndes County, Alabama, formed The Lowndes County Community Remembrance Coalition and held a virtual lynching memorial dedication ceremony for Theo Calloway. Theo Calloway was accused of killing a white man, and although he insisted that he acted in self-defense and waited to plead his case in a trial, he was abducted from jail by a mob of 200 white men. He was lynched on March 29, 1888, at the age of 24. The group hung his body on a tree in the courthouse’s lawn. The next day his parents came to attend his court hearing. Instead, they learned that their son had been lynched and had to recover his body that was riddled with bullets. Theo Calloway’s marker was installed outside of the courthouse during a small gathering that included some of his descendants on November 18.

A virtual dedication was held in December, as the original event was canceled due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The ceremony started with a solemn introduction by Arthur Nelson in which he spoke: “for the hanged and beaten. For the shot, drowned and burned. For the tortured, tormented, and terrorized”. Uplifting invocations and greetings were also given by members of The Elmore Bolling Foundation’s board and other prominent figures, like the mayor of Hayneville. Elmore Bolling’s great-grandson, J’Pierre Bolling, sang gripping renditions of Billie Holiday’s Strange Fruit, Sam Cooke’s A Change is Gonna Come, and John Legend and Common’s Glory. A forensic genealogist gave a historical account of Theo Calloway’s lynching and information about his descendants. Lastly, the organization revealed the marker in front of the courthouse.

One of the most compelling parts of the ceremony was the candle lighting when Theo Calloway and the other victims’ names were called out of the blind spot of memory while saying, “today we remember.”

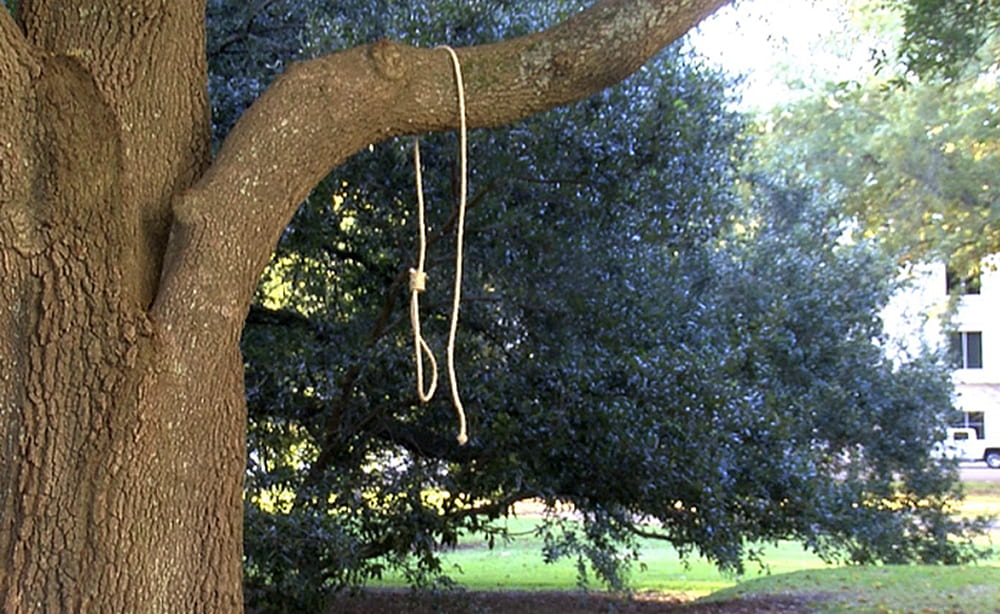

“Century Oak — A Conversation with a Tree” by E. Stanley Richardson

As I walked by

The Tree

… Cried out

Why don’t you hold me anymore

Sit beneath my shade

We barely ever talk

Like we once did

100 years ago

I know

You blame me

For being

Deep inside

Us

Hidden

In the blind spot of memory

All of

Our

Pent up

Pain

We

Must Feel

I know

You blame me

Because,

If I

Had not been

They

Would not have

Dangled

Your Brother

Your Sister

Your Father

Your Mother

… From my limbs

There would be

No blood

On my branches

I would

Be

Only brown

… Like you

With green hair

Without tinge

With

No hint of red

On

My wood

Please forgive me

Had I known

If I could

… I would have

Plucked myself

Up

By

The Root!