On October 16th, 1998, darkness set as police approached the London Bridge Hospital. They were there to arrest the former dictator General Augusto Pinochet. That Friday night, Pinochet was detained after receiving minor back surgery, the first former head of state to be arrested on a diplomatic passport in the UK. Suddenly, the immunity generally granted to persons of government had been contested, and the exiles and victims of Pinochet took a step toward justice.

Pinochet’s human rights violations

On September 11th, 1973, bombs were dropped on the presidential palace in Santiago, Chile. This was the first day in what was to be a bloody reign by the dictator General Augusto Pinochet. Overnight, the democratically elected socialist government was replaced with a repressive regime predicated on fear, oppression, and violence.

Previously, Chile had held the position as the longest-living democracy and most politically stable nation in Latin America. However, in the wake of the 1973 coup, Pinochet’s junta began a crusade to solidify power: constitutional guarantees were suspended, Congress was disbanded, and a country-wide state of siege was declared.

According to decades-long documentation by Amnesty International, “torture was systematic; ‘disappearance’ became a state policy.” These gross human rights violations were perpetrated by the Dirección de Inteligencia Nacional (DINA), the secret military police created to target the real and imagined opponents of the authoritarian regime.

On June 1974, a year after the bloody seizure of power, Article 1 of Decree-Law 521 established DINA as a “military organization of a professional technical nature, directly dependent upon the Government junta, and whose mission will be that of gathering all information at the national level coming from the different fields of activity, with the purpose of producing the intelligence which is required for the formulation of policies, planning and for the adoption of measures that seek to protect the national security and the development of the country.”

In the immediate days following the coup, hundreds of people were detained and taken to two sports stadiums in Santiago. Thousands of social activists, teachers, lawyers, trade unionists, students, and political activists became targets and prisoners of secret detention centers across the country.

These detention centers, and also labor camps, existed under the entirety of Pinochet’s reign. Villa Grimaldi was one of many of these camps used for interrogation and torture. It is estimated that 4,500 prisoners were abused at this site alone, the most common forms of torture including electroshock, waterboarding, forcing heads into excrement, rape, and death.

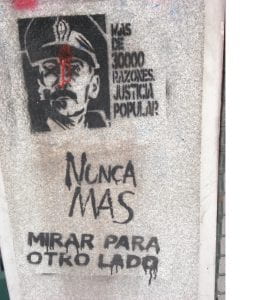

According to Amnesty International, the number of officially recognized disappeared or killed is 3,000 people between 1973 and 1990 and the survivors of political imprisonment and torture is around 40,000 people. To this day, 1,100 people remain missing and only 104 have been found.

International approaches to convict human rights violations

International law is a relatively new field. Born out of the horrors of World War Two, the United Nations is the multinational body that mediates the rules and creates the international dialogue on human rights. On December 10th, 1948, the UN passed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights comprised of 30 articles that outline the fundamental principles of human rights. Since then, the UN has written more specific conventions and treaties to expound further on the rights of:

- Women

- Refugees

- People with disabilities

- Children

- Indigenous peoples

And even civil and political, economic, social, and cultural rights.

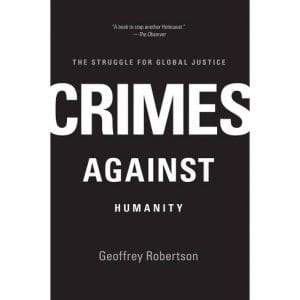

When it comes to the implementation of these conventions, there are very divergent paths in the realization of human rights. Opinio juris expresses that a norm about behavior exists but is not consistently followed. In opposition, jus cogens refer to laws and norms in which no derogation is permitted, this includes crimes against humanity (torture, war crimes, apartheid, systematic and widespread violence) and genocide.

It is the principle of jus cogens that gives rise to universal jurisdiction. Universal jurisdiction refers to the duty that all states have to prosecute individuals who commit crimes against humanity, whether domestically or by other states when the nation where the crime occurred is unwilling or unable to indict violators. It was universal jurisdiction that was key in establishing accountability during the Nuremberg Trials following the holocaust.

Fifty years later, this principle was used to arrest Pinochet for his systematic use of torture and crimes against humanity in Chile.

An end to amnesty

After democracy was restored in Chile, Pinochet lost the presidential election, but not before creating a legal structure to protect himself and his accomplices. In 1978, Pinochet passed an Amnesty Law to protect military personnel who committed human rights violations. Additionally, Pinochet remained commander-in-chief of the Chilean Armed Forces after losing his presidential position and was appointed a senator for life. It appeared, to Pinochet and his victims, that he would remain outside of a courtroom.

Instead, victims were not deterred from bringing awareness to the crimes of Pinochet. Lawyers representing victims of Pinochet’s repressive regime decided to file complaints in Spain where the principle of universal jurisdiction was enshrined in their legislation. Joan Garcés, a Spanish lawyer, had begun filing for Pinochet’s arrest in 1996, and when it was known that the former dictator would be traveling to the UK, the moment to act became apparent. On October 15th, 1998, Garcés’ team filed a motion for Pinochet’s arrest which was granted. An Interpol red notice was issued, which is a formal international request to locate and arrest persons pending extradition, and a day later Pinochet was detained.

Pinochet twice petitioned the House of the Lords to dismiss his arrest claiming immunity on the basis of being a former head of state. Both of these requests were denied as the House of Lords affirmed that former heads of state did enjoy immunity for acts committed as functions of a head of state, international crimes such as torture and crimes against humanity were not such functions. Ultimately, in March 2000 Pinochet was released and returned to Chile on medical grounds after tests found him mentally unfit to stand trial.

However, in the wake of Pinochet’s arrest, Chile’s political and legal landscape had transformed allowing more space for the voices of victims and a sweep of new legal interpretations. The Supreme Court had found the Amnesty Laws only applied prior to 1978 when the state of siege was declared over, additionally, they stated that amnesty could only be granted after an investigation. Moreover, in the cases of disappeared persons, this act constituted an ongoing aggravated kidnapping meaning these cases went beyond the 1978 cut-off.

Chilean Judge Juan Guzmán asked the courts to strip Pinochet of his immunity and the courts agreed, indicting Pinochet and placing him under house arrest.

Unfortunately, Pinochet never stood for trial, but his military officers did.

The indictment of Pinochet and new interpretations of the 1978 Amnesty Laws paved the way for other human rights violators to be prosecuted in Chile. By July 2003, 300 military officers had been indicted and dozens convicted, mostly surrounding cases of enforced disappearances. In 2017, 106 ex-agents of DINA were charged with kidnapping and killing 16 people in “Operation Colombo” during the early years of Pinochet’s dictatorship. Many were already serving times for other cases and were sentenced to between 541 days to 20 years in jail, while the state was ordered to pay around $7.5 million (5 billion Chilean pesos) to the families of the deceased.

Justice is not only a conviction of a crime. While it is vital to convict human rights violators, it can be extremely challenging, but the arrest of Pinochet has laid the foundation for other dictators to stand trial. Of equal note, this case transformed how victims were seen and heard in Chile, offering justice through legal means when possible and honoring the injustices publicly when before there was silence. Chile continues to reconcile with its past, voting to do away with the constitution written by Pinochet in place of a new one and through the tireless efforts of human rights defenders domestically and internationally.

You can offer your support or learn more below:

- Amnistía Internacional

- The Association of Families of the Detained-Disappeared (AFDD)

- Inter-American Court of Human Rights (Inter-American Court)

- School of the Americas Watch (SOA Watch)