The streets of Santiago were filled with the sounds of horns on September 4th. The vote for a new constitution had finally taken place, after three years of sustained protests, and four decades after the dictator Pinochet first replaced the constitution. The people had spoken, and the social contract between the state and the citizens was transformed.

Calls for a new constitution fueled by social movements

On October 18th, 2019, thousands of protesters flooded the streets of the capital city, Santiago, Chile. Originally, protests began over frustrations with a rise in the price of metro tickets but quickly compounded with inequality in the state. According to a Foreign Policy article on Chile’s constitutional overhaul, the massive protests were led by students, workers, farmers, indigenous peoples, and left-leaning progressives. They expressed frustrations over a lack of socioeconomic mobility, unresponsive government and institutions, and a disconnected political class. In some instances, these demonstrations included torching metro stations and tearing down statues of Spanish colonizers. To read more in-depth on the protests, read this blog.

While these protests paralyzed the capital and country for weeks, the protests demanding change resonated outside the urban center and spread across the nation. In central Santiago, Plaza Baquedano has been the place of social protest for decades, and three years on, protesters continue to use this symbolic place to voice dissent on social inequalities.

Known as the Estallido Social, or social explosion, the protests signaled a major development in the attitudes of citizens in the state. Protests eventually culminated in a 12-point agreement for social peace and a new constitution. In the eyes of many protesters, numerous contemporary problems traced back to the constitution ratified in 1980 under the military dictatorship of General Augusto Pinochet.

The citizens of Chile have expressed the need for a new constitution in order to value citizen participation. The constitution written under Pinochet leans toward a conservative interpretation and does not include any formal avenues for citizens to participate. While the Magna Carta has been changed in minimal ways since a return to democracy in 1990, the opposition claim that the constitution should be considered illegitimate since it was instituted under a dictator.

Constitutional change under dictatorial rule

On the 11th of September 1973, democratically elected socialist President Salvador Allende was overthrown by a military coup. He was given an ultimatum — to resign from his position or be detained by the Chilean armed forces.

To better understand this consequential moment, we need to understand the context of economic and political factors that had Chile on the brink of a civil war. A few times during his presidency between 1970 and 1973, Allende had made reference to President Balmaceda (1886-91), a previous executive whose conflict with the legislature led to a civil war. Allende refused to become “another Balmaceda” but also claimed he would not be forced from office alive.

In 1971, Allende began nationalizing companies, mainly copper and telephone, both previously owned by foreign US corporations. As a result, Chile stopped receiving aid from the US, and subsequently, the World Bank, the Export-Import Bank, and the Inter-American Development Bank ceased aid as well. By 1973, inflation, labor strikes, and food shortages were uncontrollable as imports had risen while exports plummeted in the face of plummeting copper prices. Soon after, General Pinochet Ugarte, chief of the armed forces, became the dictator of Chile in a violent coup that resulted in Allende’s death.

The constitution was formally rewritten in 1980 to solidify Pinochet’s regime politically and economically. In the new constitution, Pinochet protected private property to such an extent that Chile became the only country in the world to privatize water. Moreover, the constitution concentrated power in the president, from budgetary decisions to law-making. As a result, the executive in Chile remains among the world’s most powerful governing executives.

In the next two decades, thousands of people would be tortured, executed, or forcibly disappeared under General Pinochet’s repressive authoritarian rule. According to Amnesty International, the number of officially recognized disappeared or killed is 3,000 people between 1973 and 1990 and the survivors of political imprisonment and torture is around 40,000 people. After Chile returned to democracy, Pinochet was charged under universal jurisdiction for crimes against humanity.

The writing of a new constitution

After protests continued and swelled to 1 million people, the government decided in mid-November 2019 that a large concession needed to be made. A referendum was set with two questions: Should Chile replace the 1980 constitution, and if so, who should write it?

In October 2020, 78 percent of the voting population favored a new constitution, with the highest participation since the end of mandatory voting in 2012. Moreover, citizens overwhelmingly supported the new drafting by everyday citizens.

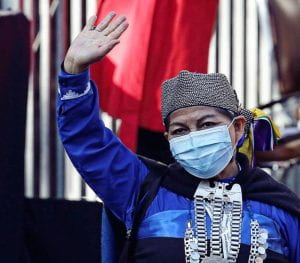

Elisa Loncon, a member of the Mapuche indigenous group, was selected as the president of the constitutional assembly. From the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, the constitutional process in Chile is the first to include an equal portion of women and men, and also includes the indigenous groups historically discriminated against.

“For the first time in our history, Chileans from all walks of life and from all political factions are participating in a democratic dialogue,” Loncon said.

Not only had the social protests begun a sweeping institutional change in the country focused on the economic and political rights of people, but this moment also signaled a significant expression of self-determination.

The process has received help from the UN Human Rights Regional Office for South America which has provided accessible documents, webinars, and publications on the international framework for human rights.

The resulting constitution embodies the standards of human rights law, with rights focused on indigenous people, women, LGBTQ+ people, people with disabilities, and the environment. Also, the new constitution ensures adequate housing, the establishment of a national healthcare system, employment benefits, and mandatory gender parity in the private and public sectors. This new charter represents a sweeping array of human rights, from civil and political to economic, social, and cultural.

Valentina Contreras, the Chilean representative of the Global Initiative for Social, Economic, and Cultural Rights, said “Human rights are the common thread of the constitutional process.”

Rejection and steps forward

The vote for the new constitution was this September 4th, 2022. After two years of drafting the new constitution, 62 percent of Chileans voted against the new Magna Carta and only 38 percent for it.

The National Public Radio reported on the results of the plebiscite. While most states normally rewrite their constitutions during or shortly after the democratic transition, Chile remains an outlier. Additionally, most new constitutions are short, but in this case, the proposed Magna Carta was 388 articles long and considered “confusing” according to Claudio Fuentes, a Santiago political analyst.

This aided a large disinformation campaign launched by more conservative and centrist citizens, claiming the proposed constitution would disarm the police and confiscate people’s private homes. Still, other citizens saw the draft as a product of anger and tension, identifying the new text strongly with the violent protests that had originally spurred its creation.

This represents a loss not only for the constitutional assembly but a commitment to a broad range of human rights. However, as Gabriel Boric, the current president of Chile stated, “You have to listen to the voice of the people.” Extensive social protests first began the move to redefine the social contract between citizens and government, and now democratic procedures have determined the continuance of this process.

This process is not over, Chileans are still waiting on a new constitution. Centrist-left and right-wing politicians have expressed interest in working with the government on the next draft.

Ultimately, while Chileans voted against the proposed constitution, this remains a poignant moment for human rights. Firstly, the level of dialogue on such topics from people of varied backgrounds and historically discriminated groups remains unprecedented in Chile and illustrates the unfettered self-determination of a people. From people organizing and demonstrating their rights to cooperation between radically different political parties, the constitutional assembly remained committed to a document based on human rights.

Students have once again begun protesting at metro stations in response to the rejection. This dialogue will not stop with the constitutional committee, instead, it has and continues to be embodied by the protesters who sparked the original rewrite.