This blog is part three of the conversation around disability rights, especially as it applies to children within the American school system. If you have not read the first two blogs in this series, I suggest you do so. The first blog focused on the historical view of disability and the American school system’s approach to children with disabilities. The second part mainly focused on the struggles that children with disabilities face within the school system, and how these struggles have been exacerbated due to the recent pandemic. This final part will focus on some of the approaches that have been taken in the past to address people with disabilities, and how they differ from a human rights approach. We will also examine how we can help on various levels, whether we want to focus on our personal abilities or advocate for a larger movement.

The Rights of Children with Disabilities

What rights are protected?

Much of what we have established in modern society in terms of children’s rights comes from decades of struggles, from implementing child labor laws to fighting for the right to an education. Similarly, the fight to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was one sure way to protect individuals with disabilities from discrimination. These rights and more are protected under the United Nations, both in terms of people with disabilities, (Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, CRPD), and with children’s rights (Convention on the Rights of the Child, CRC). Yet, these developments have only occurred in recent years; the ADA and the CRC were passed in America and the UN respectively, in 1990, and the CRPD was not adopted internationally until 2006.

The ADA, passed in the United States, protected the rights of people with disabilities from being discriminated against in all aspects of society. This was the first major legislation that protected people with disabilities from being denied employment, discriminated against in places of business, or even denied housing. In addition to these protections, the ADA required industries to be inclusive of those with disabilities through (among other things) taking measures such as building ramps and elevators for easy access to upper-level floors and building housing units with people with disabilities in mind. While America had passed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or IDEA (originally passed in 1975, and renamed in 1990) by this time, the initial form of this legislation allowed schools to place certain students with disabilities in special programs for no more than 45 days at a time. It was not until its improved form was passed in 2004 that provided the necessary financial and social infrastructure for its successful implementation.

The passage of the CRC, which applies to all individuals under the age of 18, focuses on non-discrimination, the right to life, survival and development, the State’s responsibility to ensure that the child’s best interests are being pursued, including ensuring that the child has adequate parental guidance. Additionally, it focuses on the child’s right to free expression, free thought, freedom to preserve their identity, protection from being abused or neglected, adequate healthcare and education, and includes certain protections the State is required to offer the children, including protection from trafficking, child labor, and torture. Article 23 of this Convention specifically focuses on the rights of children with disabilities, adding that these children have the right to the care, education, and training they need to lead a life of fulfillment and dignity. It also stresses the responsibility of the State to ensure that children with disabilities can live a life of independence and protect them from being socially isolated. Even though the UN passed this Convention in 2004, America is the only nation that has yet to ratify this treaty. This is why certain realities continue to exist, such as what is happening in Illinois.

Finally, we have the CRPD, which entered into force in 2008, only 15 years ago. Influenced by the ADA, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was passed to ensure that people with disabilities were fully protected under the law, including from discrimination, with the ability to function as fully pontificating citizens of their societies, with equal opportunities and the right to accessibility in order for them to lead a life with the dignity and respect afforded to their able-bodied counterparts. This convention had massive support and draws from both a human rights focus and an international development focus. What makes this convention unique is the implementation and monitoring abilities embedded within the treaty itself, and it includes non-traditional actors from communities (usually those with disabilities) with specific roles in charge of monitoring the implementation of this treaty. Unfortunately, the United States, while Obama signed the treaty and passed it to the Senate for their approval in 2009, has yet to fully ratify the CRPD treaty as well.

Some Approaches to Disability Rights

Upon understanding the various nuances of this conversation, we can now explore the three different approaches to defining disability in society. These approaches examine the issues that people with disabilities face and provide models influenced by differing fields of expertise. Many within society view disability as a medical issue and their solutions to the struggles faced by people with disabilities are medically focused. Similarly, others believe that disability is an issue of how society is structured, and their proposals for solving these issues lie within the realms of reshaping society to be more accessible to people with disabilities. Still, another approach built upon the foundations of human rights, focuses on the individual first, and the disability as an extension of their individuality. We will explore these three approaches and their pros and cons.

Approach 1: Medical Model of Disability

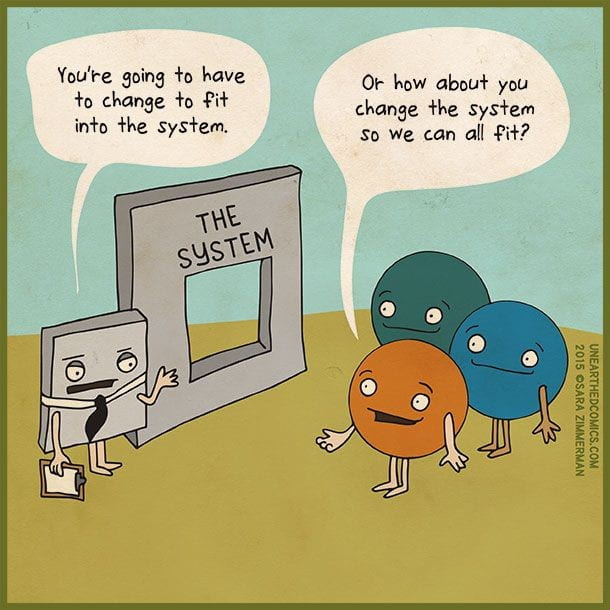

As mentioned above, some people view disability as a medical issue, and this approach can be categorized as the medical model of disability. This means that they believe that the “problem” of disability belongs to the individual experiencing it and that disability comes from the direct impairment of the person. The focus of this approach is to look for medical “cures” for disability, which can only be provided by medical “experts” based on the specific diagnosis. While it may be true that individuals with disabilities require medical help from time to time, their entire existence does not revolve around this notion of viewing disability as an illness. The focus here is to “fix” the person with disabilities, so they can become “normal” again. This approach also makes use of the “special needs” rhetoric, which can result in the isolation and marginalization of people with disabilities. Media plays a big part in portraying people with disabilities as weak or ashamed of their disability, which can invoke fear or pity for people with disabilities within the larger society.

Approach 2: Social Model of Disability

Another approach that has been proposed is what is known as the Social Model of Disability. In this approach, the “problem” of disability is seen as a result of the physical and social barriers within society that exclude people with disabilities from fully participating in their society. Disability is seen as a political and social issue, and the goal of this model is to be more inclusive and recognize the prevalence of disability within our societies. This means looking closely at the ableist social institutions and infrastructures present within society and attempting to address these manmade challenges posed by people with disabilities. This model recognizes the social stigma around disabilities and recognizes people with disabilities as differently abled rather than viewing them as incapable of living an independent lifestyle. This approach places individuals with disabilities on a spectrum rather than the two categories of disabled and able-bodied. The goal of this approach is to be socially inclusive of all individuals, regardless of their disabilities.

Approach 3: The Human Rights Model of Disability

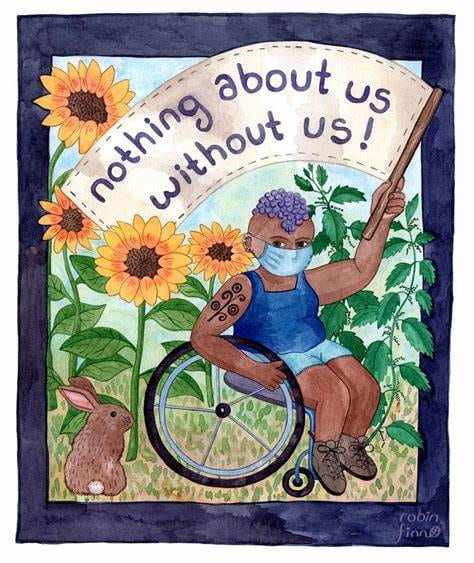

Finally, there is the Human Rights Model of Disability, which builds upon the foundations laid out by the Social Model of Disability and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). In this approach, the focus is on viewing the individual with a disability as a human first, recognizing that disability is a natural part of humanity that has existed as long as humans have been around. While it shares a lot of similarities with the social model, the human rights approach emphasizes not only the right of every individual to be treated equally before the law but also stresses that a person’s impairment should not be used as an excuse for denying them rights. This is essentially what the CRPD centers around, and the main goal of this approach is to ensure that people with disabilities have equal opportunities and protect their right to fully participate in society, politically, civilly, socially, culturally, and economically.

How Can We Help?

On the Internation Level

While the United Nations has a convention that focuses on protecting children’s rights, it is highly debated whether these treaties are being enforced around the world. Child labor is still common in various places around the world, including right here in Alabama. While it can be argued that the US has not ratified the treaty and that is why the UN cannot do anything about this issue, there are other places that have ratified the treaty that still places children in dangerous working conditions and face no real repercussions from these decisions from the UN. In 2019, many tech companies were sued for their use of child labor in other countries to mine the precious minerals they require to produce their devices. Many textile companies within the fashion industry use child labor in nations that have ratified the children’s rights treaty. While the United Nations is trying its best to protect and promote the rights of vulnerable communities, it has not been able to enforce these treaties and regulations, and as a result, atrocities against those vulnerable communities, (including children), continue to occur. How can we as human beings, ensure that all children are protected from harm, not just those able-bodied, living in wealthier nations? This is something that needs to be addressed, and it requires the cooperation of many different nations willing to put their differences aside and work together to find a solution.

On the Domestic Level

As we explored in the human rights model of disability rights, it is the responsibility of society to provide equal access to all its citizens. This includes its citizens who have disabilities, and not doing so would discriminate against those who have disabilities and violate the Americans with Disabilities Act. This means that both on a national and local level, our infrastructure needs to be updated with an inclusive mindset that makes the roads safer and more accessible to all the citizens using them. As a state, Alabama could not only fix the infrastructure, but also pass bills to ensure that people with disabilities receive the care they need, including employment opportunities, medical assistance, food assistance, and any financial help they may require. Furthermore, on a national level, the police (or another department focused on social work) can be better trained to recognize the various disabilities, both visible and invisible, so people with disabilities are not wrongfully imprisoned for “behavioral” issues. This training would help erode the school-to-prison pipeline that has replaced disciplinary standards in American schools and make way for a brighter future for children with disabilities. Finally, the United States can, at the bare minimum, ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child, signed into existence in 1990 by member states of the United Nation. As we mentioned earlier, the United States is the only nation in the world that has yet to ratify this treaty.

On the Individual Level

We can all be more mindful of our actions and our ableist mindsets. Next time you walk down the street, pay attention to the roads and sidewalks. Are there any sidewalks for people with disabilities to use safely? Are there curb cuts, and are those curb cuts freely accessible or are they blocked? How accessible are public buildings such as restaurants, storefronts, or even the DMV? Are there enough parking spots allotted to people with disabilities, and are those spots easily accessible, or blocked off by other vehicles? Thinking outside of an ableist mind frame is the first step toward being more inclusive of people with disabilities. It might seem like a powerless and pointless step to take, but the more you start to notice the ableist structures within society, the more you will want to speak up about these issues the next time you have the opportunity. You will also be more mindful of your own ableist actions and how they may have unintended consequences. If you are a parent, you have the ability to question your school’s practices concerning children with disabilities and offer support to the children and their parents. As an individual, you can also contact your representatives to pass legislation that would empower people with disabilities to live independently. As a society, we need to get past the stigmatization of this group and normalize disability being an innate part of being human.