Just like many who grew up in the Southern United States, I spent much of my childhood outside. I was born in a suburb of Birmingham, and as a child, I would play in the Cahaba River and bask in the beauty of the short leaf pines and oak trees that towered high in magnificent forests.

I may not have known it then, but my ability to enjoy the natural beauty of my home in an unaltered way was not being protected in a concrete way. As our environment continues to degrade from the ongoing climate change disaster, human rights activists have begun championing environmental rights. Eloquently defined by the Pachamama Alliance, environmental rights can be understood as “an extension of the basic human rights that mankind requires and deserves. In addition to having the right to food, clean water, suitable shelter, and education, having a safe and sustainable environment is paramount as all other rights are dependent upon it.”

2021 brought lots of bad news for the environment. Despite much more attention from activists and the general public alike, promises from the United Nations Climate Change Conference 2021 (also known as COP26) seem to ring empty, as nations who pledged to cut emissions continue to approve new fossil-fuel based plants for power generation.

Despite this, it is important for activists to celebrate victories, however small their size or infrequently they occur. In the United States, this week marked a huge victory for the restoration of the Everglades

The Everglades, a History

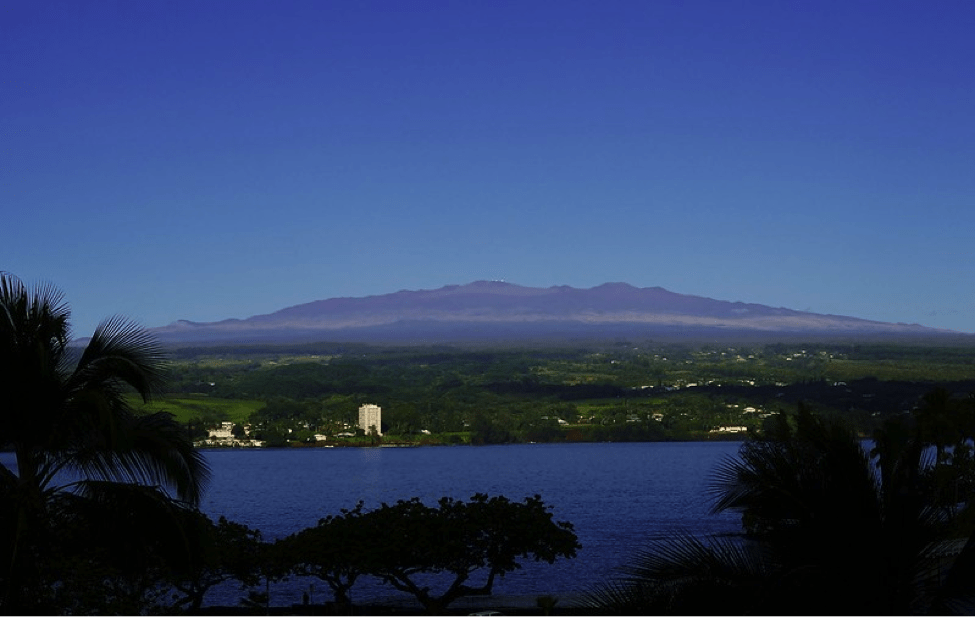

The Everglades, an ecosystem in southern Florida, has been called “one of the world’s most unique and fragile ecosystems”. Many people believe that the Florida Everglades is a swamp ecosystem, though this is just a popular misconception. In reality, the Everglades is actually a slow-moving river flowing over an area 40 miles wide by 100 miles long.

The Florida Everglades was formed over many thousands of years, creating a delicate balance of ponds, marshes, and forests. The Everglades have been inhabited for at least 14,000 years by human beings with the arrival of the first indigenous peoples to the area. When European settlers first arrived to the area in the early 1800s, the Everglades were considered little more than a “worthless swamp”, and work to drain the wetlands of the Everglades quickly began. By the early 20th century, much of the Everglades was in the process of being converted to farmland, and this stimulated the first “land boom” in Southern Florida.

As the Everglades began to shrink, Florida’s population began to boom as cities like Miami and Fort Lauderdale grew, increasing the demand for housing and fueling further destruction of the Florida Everglades.

As the American environmental movement began in response to extreme environmental degradation across America and the extremely important work of early climate activists such as Rachel Carson (whose 1962 publication of Silent Spring is to this day considered to be a milestone of modern environmentalism), activists began to realize the extreme importance of the Florida Everglades. According to the Naples, Florida Travel Guide, “People like author and activist Marjory Stoneman Douglas who organized the Friends of the Everglades in the 1960s to battle the federal government’s plan to build an airport in the Everglades”, which thankfully worked. Activists like Douglas helped preserve the Everglades the best they could, allowing us to begin restoration work on the Everglades.

It is also worth noting that the Everglades have been classified as a national since 1947, entitling the wetlands to federal protection and further bolstering the Everglades as one of America’s most sacred national treasures.

The Everglades Today

Once sitting at over 4,000 square miles in size, deforestation and environmental degradation have reduced the Florida Everglades to about half of their original size. The number of endangered species in the Everglades, both flora and fauna, continues to increase at an alarming rate. Among these endangered species is the Florida Panther, which now occupy less than five percent of their historic range, which once included the entirety of the Southeastern United States. It is thought that less than one hundred Florida panthers exist in the United States today.

One of the largest threats to wildlife species in the Everglades is the introduction of invasive species to the area. These non-native species are often accidentally introduced by human beings, and they can quickly destroy the balance of a delicate ecosystem, such as the Everglades. One of the most famous invasive species in the Florida Everglades is the Burmese Python, which was believed to be introduced into the area by Hurricane Andrew, a category five storm which struck Florida in 1992, destroying a python breeding facility and releasing dozens of snakes into the surrounding Everglades.

A Historic Investment into the Everglades

On January 19, 2022, the Biden Administration announced a historic $1.1 billion allocation of funds towards the restoration of the Everglades. The funding will come from the Bipartisan Infrastructure Bill, which was signed into law by President Biden on November 15 of last year. An announcement by the White House declared that this allocation was “The largest single investment ever to restore and revitalize the Everglades in Florida”.

The announcement was seen as a huge political victory for the bipartisan Everglades Caucus, which is currently co-chaired by U.S. Representative Debbie Wasserman Schultz (D-FL) and U.S. Representative Mario Diaz-Ballard (R-FL). Representative Schultz released a statement following the historic announcement highlighting the importance of the restoration of the Everglades :

“The Everglades is the lifeblood of South Florida, and this historic funding commitment by the Biden Administration will ensure we can much more aggressively move to restore and protect the natural sheet flow of water that is the largest environmental restoration project in American history. The Florida Everglades is a vital source of drinking water and essential to combat climate change and this massive infusion of funding will have the added benefit of creating more jobs,” showing the real human opportunities that will be created by this new investment.

Restoration of the Everglades will also help ensure continued access to clean drinking water for Florida’s population. The Everglades currently provides water to over eight million people across the state. Activists across the state remain cautiously optimistic as the plan will begin to come into effect later this year. The future for one of the world’s most fascinating ecosystems appears to be finally be headed in the right direction, ensure access and protection for our descendants.