On April 28, 2018, I graduated from the University of Alabama at Birmingham with a Bachelor’s of Science in Public Health with a concentration in Global and Environmental Health Sciences. As I reflect on my journey, I want to recognize and express how thankful and fortunate I am to receive an education, knowing so many other young adults just like me may never get the opportunity. Second, I want to thank my biggest support system of all, my parents, because I know this wouldn’t be possible without your sacrifices!

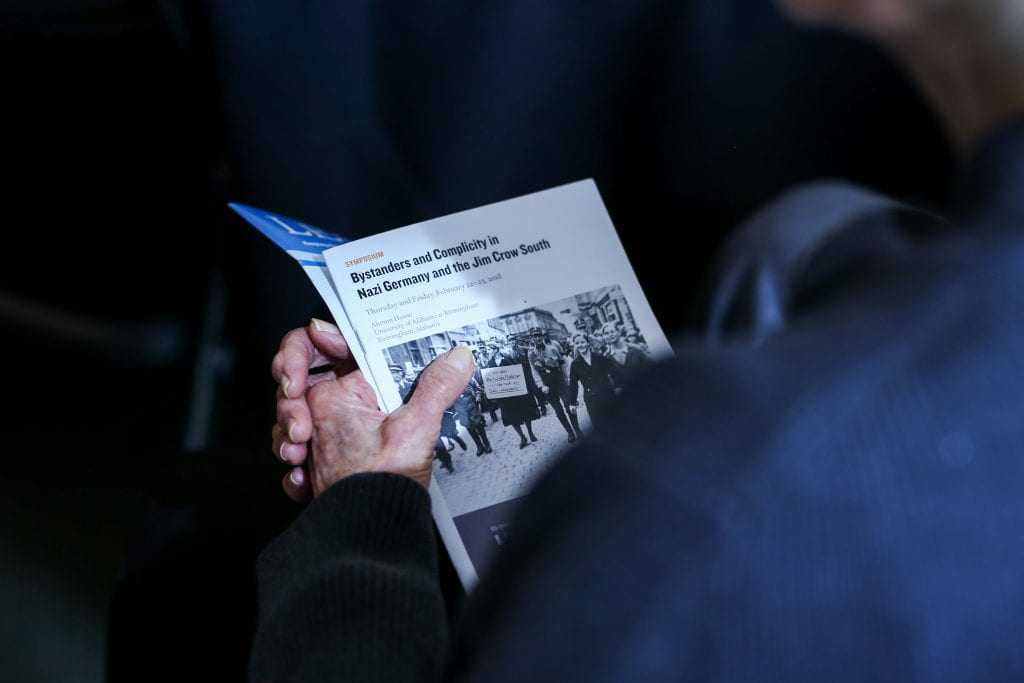

Before interning at the Institute for Human Rights at UAB (IHR), I did not have extensive knowledge about human rights issues nor human rights in general. However, during my sophomore year, I took Dr. Reuter’s Human Rights course. This class helped me realize my passion for human rights, specifically the intersections between public health and human rights, which sparked my current interest in this field. Fast-forward to my junior year, I find out the IHR has a blogging internship position open. I knew if I joined this Institution, it would be the perfect opportunity for me to explore and learn more about my personal interest and goals, but also about potential careers and academic fields of interest. I was right. Here’s why:

First, for students like me (interested in human rights and public health), the IHR has been one of my main opportunities for: 1) networking with guest speakers and organizations, 2) learning about open internship and academic opportunities, and 3) tackling current IHR research projects. The IHR is a very self-paced environment, and the student can really shape their own experience at the IHR.

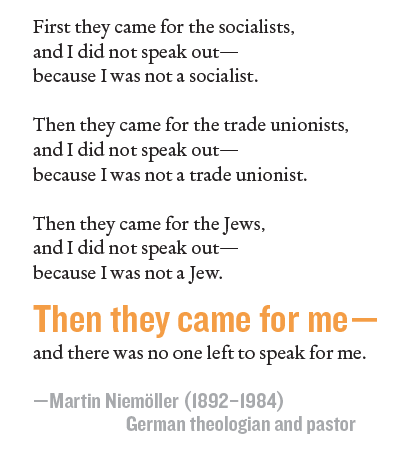

Second, working at the IHR has helped me grow as a student and professionally. Before joining the IHR, I never used to write, so writing two blogs a month was a challenge. As a student who originally did not enjoy writing, blogging pushed me as a researcher by forcing me to continuously practice my writing and communication skills. Comparing my first blog written a year and a half ago to my last one, I can see the improvement in my writing. It has been very rewarding noticing improvements in my writing because written communication is such an important life skill. As a recent graduate, I can honestly say I am more than thankful for the opportunity to practice my written communication skills. Although writing is a skill that can always improve, I now feel more confident and prepared to apply for jobs, graduate schools, and other career-furthering opportunities by knowing I am capable of effectively representing myself and my beliefs. Although I have graduated, writing for the blog is something I wish to continue to do because I know it will only keep helping me grow.

My favorite blog I wrote throughout my time at the IHR: Angelique Kidjo and the Importance of Education. This is because I have a passion for education and hope to focus parts of my career on promoting female education. I personally understand the power education has over breaking the cycle of poverty. My father was the first one in his family to receive a college education. In return, he was able to seek more advantageous economic and life opportunities, and eventually provide my siblings and me all the prospects he could never afford growing up. Education literally changed my life. Writing these blogs made me realize the importance of advocacy. As I write human rights blogs, I learn something new every time, and it is this new information I learned that inspires me to want to possibly educate and inspire other people. I am very proud to be part of this educational advocacy process because it allows me to contribute to a community and something bigger than myself. That being said, on March 23, 2018, Angelique Kidjo came to UAB and performed such a lively musical performance. After her performance, we got to meet Angelique Kidjo and take photos with her, which of course was very fun. Her energy was very inspiring, and moments like these help me remember why I want to have a career in human rights and public health.

My favorite memory with the IHR is when we went to the United Nations to volunteer at the 10th Session of the Conference of States Parties to the Conventions of the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (COSP10). This experience was amazing for two reasons:

- going to New York with the rest of the team was so much fun. I have personally never visited a megacity like New York, so it was definitely a new experience. The most fun part was absolutely riding the subway, occasionally getting lost, and kind of living the New York life style for a week.

- it exposed me to potential career fields. I have always wanted to work with the United Nations or an UN-related agency and being able to experience what a career at the UN entails was very important to me. It helped reaffirm my vision of building a career in these kinds of agencies and organizations. Working for the UN once, and knowing I want to go back one day, helps me stay motivated to continue striving for my goals.

Along with everything I have learned, the IHR also brought me such a special support system and friendships that have made my time at UAB so memorable. That being said, I would like to say thank you to my team, especially Dr. Reuter, for all the support and good memories! Graduating and leaving the IHR is a bittersweet moment. The IHR is such an exceptional platform, and I am confident it has prepared me to continue spreading my knowledge about human rights. Overall, I can’t wait to learn more about human rights, and the IHR is only the beginning!