Introduction

My sister is in middle school.

She is in VIRTUAL middle school, spending almost all her time in her room physically and mentally connected to her computer for more than five hours a day, Monday to Friday.

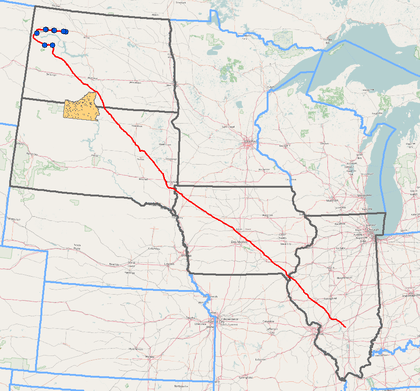

Two weeks ago, our family received a voucher in the mail giving us the chance to receive internet service for free until December 30th, 2020. The vouchers come from a program known as the Alabama Broadband Connectivity (ABC) for Students. The goal for this program is to provide “Broadband for Every K-12 Student.” ABC uses money from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act directed to Alabama ($100 million) in order to cover the costs of “installation, equipment, and monthly service” to all students “who receive free or reduced-price lunches at school.” Families who earn less than 185% of the federal poverty level ($48,470) are those considered eligible for the vouchers, including 450,000 children enrolled in the National School Lunch Program.

Which brings me to the topic of this blog post: Internet Access, and why it is so important given this day and age.

Now, I know what you might be thinking, “Yes, the coronavirus is still a major issue among governments today, and since people cannot really gather outside in large groups, the internet is the next best option. That’s why it is so important to have access to it.” Great, at least you understood that part, but what if I told you that there are governments around the world shutting down the internet, from India to Russia and even countries like Indonesia, in the attempt to resolve their problems?

Shocking right? I would personally think so.

But before we talk about Internet Access as a potential human right, let us talk about some of the things that we take for granted when we have internet access.

How do we benefit from being online?

Instant Communication

-

- We often tend to talk to others by text, rather than face-to-face. Texting allows people to communicate in speeds never thought possible in the past, which leads to an eventual disconnect in establishing a fully personal connection that people would have if they interacted in person.

Homework

-

- Especially during these times, we need the internet in order to complete our homework, and not having that access most definitely leads to an inability to do work as efficiently as if we had access to the World Wide Web.

Yes, even the Weather

-

- How many people check the weather before leaving their homes? Checking the weather resides among the most popular search terms, which makes sense, as people need it to avoid downpours and be prepared to any eventual changes in plans.

Opinions against Internet Access being a Human Rights

Reflecting on the above benefits really does help broaden one’s vision in understanding how connecting to google.com or other web sites is essential to the daily happenings of our lives. It makes sense to simply call access to the internet a human right because of the way most of us use the internet to live our lives more efficiently.

Well, before we explore the arguments why Internet Access should be a human right, let us look at two perspectives to the contrary, an NYT op-ed by Vinton Cerf, an “Internet pioneer and [who] is recognized as one of ‘the fathers of the Internet,'” and a statement by Commissioner Michael O’Rielly of the Federal Communications Commission.

According to Cerf, for something to be considered a human right, it “must be among the things we as humans need in order to lead healthy, meaningful lives,” In that end, he argues that access to the Internet should be an enabler of rights, but not a right itself.

“It is a mistake to place any particular technology in this exalted category (of human rights), since over time we will end up valuing the wrong things.” — Vinton Cerf

He then attempts to clarify the lines at which human rights and civil rights should be drawn, concluding his op-ed with an understanding that access is simply a means “to improve the human condition.” Granting and ensuring human rights should utilize the internet, not make access the human right itself.

While Cerf seems to believe that the internet is a necessity for people but not a human right, O’Rielly believes otherwise, making it neither a necessity nor a human right.

In a speech before the Internet Innovation Alliance in 2015, Michael O’Rielly introduces his guiding principles with a personal anecdote about his life, emphasizing the impact that technology has given him, even going so far as to claim it as “one of the greatest loves of [his] life, besides [his] wife.” Despite this personal love for technology, one of his governing principles is to clarify what he believes the term ‘necessity’ truly means. He claims that it is unreasonable to even consider access to the internet as a human right or a necessity, as people can live and function without the presence of technology.

“Instead, the term ‘necessity’ should be reserved to those items that humans cannot live without, such as food, shelter, and water.” — Michael O’Rielly

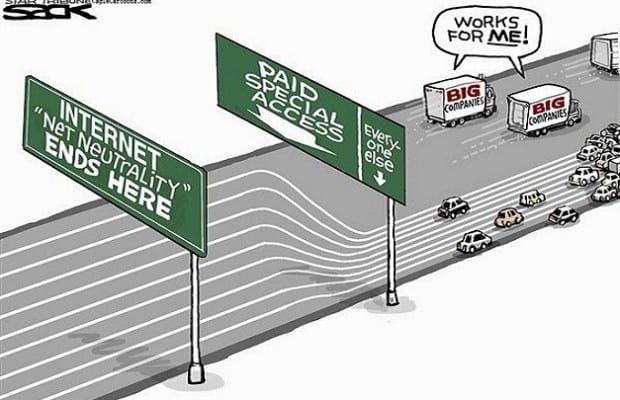

O’Rielly attempts to make the distinction between the true sense of the word ‘necessity’ and ‘human rights,’ trying to defend against “rhetorical traps” created by movements towards making Internet Access a human right. These definitions are the basis of his governing principles and how he attempts to create Internet policies with the government and ISPs (Internet Service Providers).

Opinions for Internet Access being a Human Right

One of the interesting things to note above is the distinction made between one’s need for Internet Access and its categorization into a human right. Today, many if not all businesses require the usage of the Internet, going so far as to purely rely on its presence for regular business transactions and practices to occur. This understanding of the importance of the internet is prevalent now more than ever. The onset of COVID-19 has forced businesses to shut their physical door, allowed for increased traffic of online e-commerce sites like Amazon, and pushed kids towards utilizing platforms like Zoom, Microsoft Teams, and Google Meet as substitutes for attending school. As such, these next few paragraphs will discuss why Internet Access is, in fact, a human right.

Violations to internet access are prevalent around the world, ranging from countries like India and Sri Lanka to others like Iran and Russia, aiming to either curb resistance or reduce potential sparks of violence. In India, for example, the government had shut down access to the Internet for Indian-administered Kashmir, an action that brought the condemnation of UN special rapporteurs, where the regions of Jammu and Kashmir experienced a “near total communications blackout, with internet access, mobile phone networks, and cable cut off.” In Sri Lanka, only specific applications are blocked by the authorities, while Iran works to slow “internet speeds to a crawl.” The internet system in Russia allows for it to seem like it functions while no data is sent to servers. These systems aim to restrict journalists from spreading news about violations of human rights while also limiting people’s ability to freely express themselves.

This attempt to curb the spread of information also violates Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, of which India and Iran voted in favor, the Soviet Union abstained, and Sri Lanka was nonexistent during its passage (accepted by the General Assembly in 1948).

“Everyone has the right to freedom of opinion and expression; this right includes freedom to hold opinions without interference and to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media regardless of frontiers.” — Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights

Conclusion

There seems to be a fundamental agreement from many experts ranging from the United Nations to organizations like Internet.org that aim to connect people with others around the world, that Internet Access should become, or already is, a basic human right. Although arguments are made that the internet allows for freedom of speech and enable other rights to exist, accessibility to that medium of communication and connection should be guaranteed as food or water. Although the internet is not needed for physical survival, the internet is a requirement for advancement and productivity in life.

Which brings me back to the first point made. I am thankful to have a family and live in a home where I can access information and write blog posts about human rights all around the world. What about those living within my city, my state, the United States, or even Planet Earth who do not have that access to the Internet? What about people that cannot connect with people miles away from them, or people who cannot receive an education due to the environmental factors that affect us now.

Access to the internet is a critically important task that governments, local, state, and federal, all need to act upon in order for a successful and growing economy, not just for current businesses and enterprises, but for the future leaders of our country. It is during these trying times that disparities and inequities are revealed, and those in power must be held accountable for a connected and thriving population to exist.

If you would like to learn more about Internet Equality and the case for Net Neutrality, I encourage you to read my previous blog post “Internet Equality: A Human Rights Issue?”