As the COVID-19 outbreak crosses borders throughout the United States, the Center for Disease Control has released recommendations for maintaining public health, which includes working from home, hand washing, and staying six feet away from any person, if possible. For the past few weeks, I have noticed people in my own community adapt to this new way of life. Kroger and Home Depot put masking tape six feet apart in the checkout lines, and every company I’ve ever heard of has sent me a helpful email explaining their own “pandemic plan.” Amidst the anxieties associated with this global pandemic, focus understandably turns to our immediate family and community. I may get frustrated about the lack of toilet paper in my local grocery store, but millions are incapable of following any of the CDC’s guidelines. Areas with a lack of hand-washing stations, affordable healthcare, clean water, internet, housing, and infrastructure do not allow for proper social distancing. Even at the United States’s southern border, relief agencies are struggling to address the growing pandemic.

Thousands of migrants along the United States-Mexico border are stuck in limbo. Many have fled from Central America, fleeing domestic violence, gangs, and death threats, to seek shelter in the United States. However, due to the threat of COVID-19, “The U.S. closed its border to asylum-seekers, Mexico suspended refugee processing, and many migrants are afraid to go home to their native countries, even if it were safe to travel.” Therefore, people seeking asylum are left on their own to find shelter, food, water, and medical care in a place that lacks these things when there is not a global pandemic occurring. Volunteers that would usually come to help have been quarantined, basic supplies have become hard to find due to panic buying, and any assistance from medical staff has been stretched thin as case numbers continue to rise in both Mexico and the United States. Additionally, asylum-seekers have to be concerned for their own safety even after they have made it to the border and received a court date for immigration hearings. Human trafficking, sexual assault, and gang violence are all risks in the camps, and since immigration hearings have been put on hold indefinitely, asylum-seekers have to wait even longer in these dangerous areas. Aid efforts become increasingly complex with more restrictions put in place by Mexican and United States governments each day.

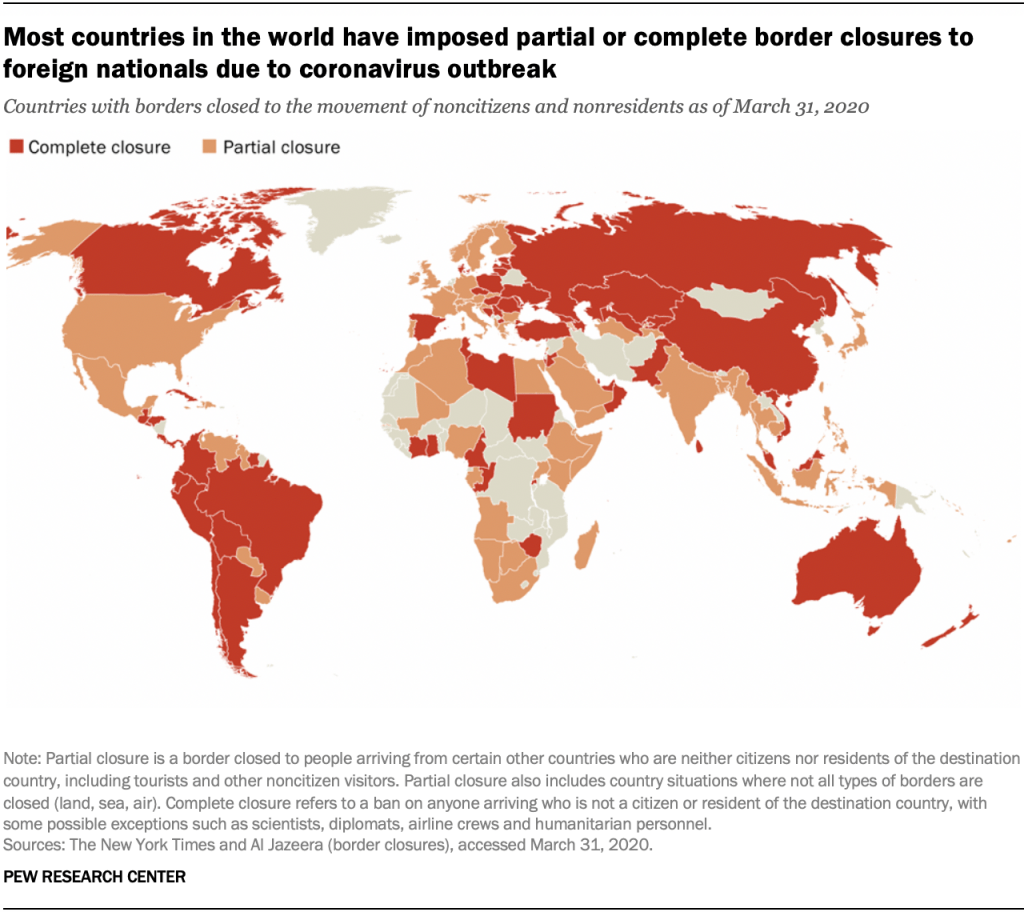

As economies are negatively impacted by the virus, countries are becoming increasingly isolationist. 90% of the world’s population currently live in countries with restricted travel, while almost 40% live in countries with closed borders. These countries include Canada, China, Japan, and Ecuador, with Greece suspending asylum claims at its border with Turkey, much like the United States’s current policy with asylum-seekers at its southern border. Millions of United States citizens have filed for unemployment, and businesses and individuals are struggling to stay financially afloat and pay rent. It makes sense that countries like the United States are turning their attention to the plight of their own citizens, but according to the United Nations (UN) Secretary-General Antonio Guterres, “If we let the virus spread like wildfires, especially in the most vulnerable regions of the world, it would kill millions.” For many relief agencies and nonprofits, grants and funding for the year have already been distributed. However, the funds are typically earmarked for certain programs. Unfortunately, many of these programs, like funding for computer education, community engagement, and language classes, cease to exist in a world with COVID-19. Now, funding is needed to help displaced persons combat the threat of COVID-19, but it would require authorization to transfer funds from one program to another. Jan Egeland, Secretary-General of the Norwegian Refugee Council, has said that banks have not financially supported relief agencies who would help UN sanctioned countries like Iran and North Korea because they fear being sued by the US government. Bureaucratic lag in providing humanitarian resources will likely mean death for thousands, particularly those with limited resources. With donor countries being overwhelmed with their own coronavirus crises, where would the funding come from?

War-torn countries and refugee camps in countries like Syria and Sudan receive assistance from the UN in the form of educational, medical, and financial resources. When we see pictures of a child fleeing violence and war in Syria, it is understandable why the UN would come in to help. However, rhetoric around the US-Mexico border paints a different picture. Often, this population is thought of as simply a group of people seeking the “American dream”. In truth, these asylum-seekers and refugees are fleeing for their lives, just like refugees on other continents. Regardless of opinions surrounding citizenship and legal status, the reality is that thousands of people have come to this region to escape deadly violence. Executive Director of Global Response Management (GRM), an organization that provides medical care to vulnerable populations worldwide, Helen Perry explains the unique situation, “There’s not a lot of great oversight. Normally in a displacement situation, the UN would come in at either the request of the country they’re fleeing from or the country that’s receiving them…but unfortunately at the border that’s not happening because both governments [Mexico and the US] are sort of unwilling to admit that there’s a problem.” As a former nurse in the US Army, Perry is especially adept at assessing the needs of struggling communities. When she came to the US-Mexico border for the first time in 2018, she was surprised to see people facing similar levels of violence to patients she had helped in Yemen who had fled the Civil War there. Fortunately, her organization continues to provide aid along the border, but COVID-19 adds an additional layer of complications. The dire situation described above was her take last year, and her organization has had to make adjustments due to the pandemic, including creating a makeshift hospital. They’re not the only organization building makeshift shelters. A government agency tasked with building the US-Mexico border wall is currently creating semi-permanent lodging for its construction workers so they can continue building, despite concerns at COVID-19. These workers, like asylum-seekers on the other side of the wall, are worried about their health and how a lack of resources could impact them and their families.

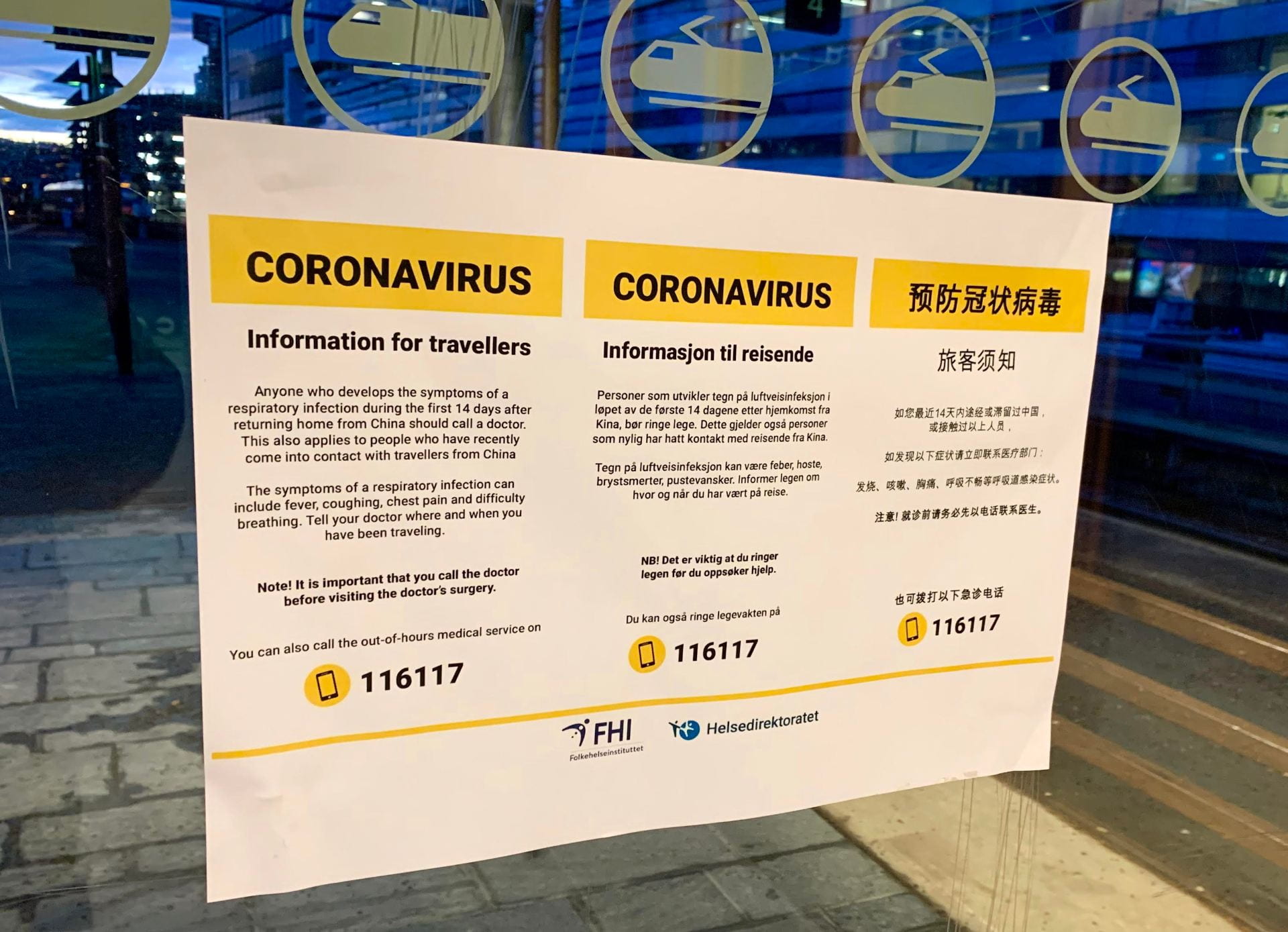

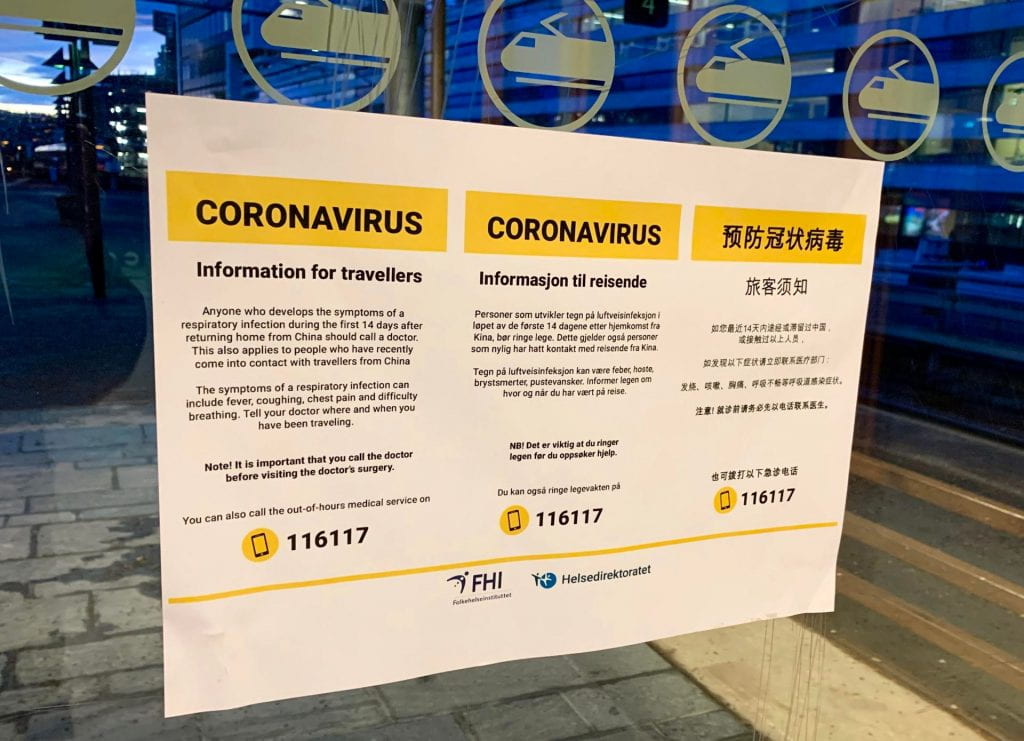

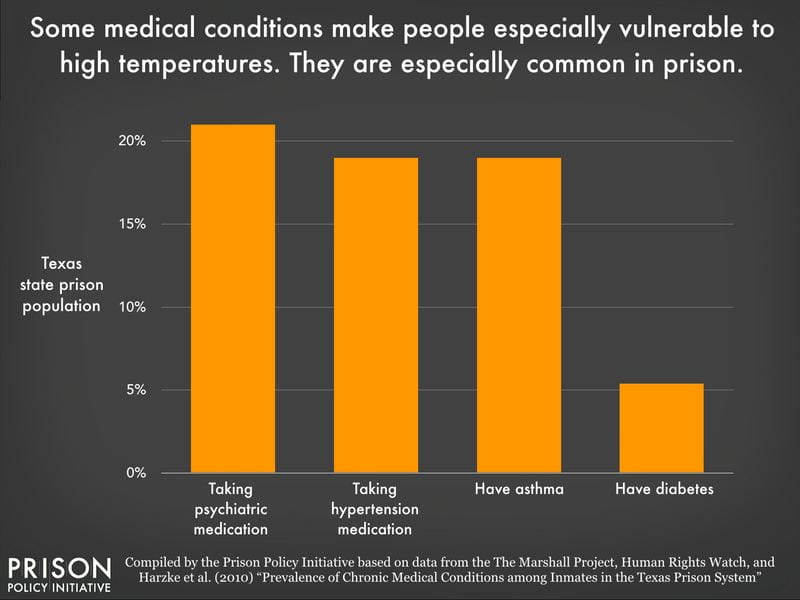

Asylum-seekers and refugees have limited access to news updates, so there is a lack of knowledge in the camps about COVID-19 and its impact. Border towns like Tijuana are already overwhelmed with patients who are US citizens, so it would be virtually impossible for a non-citizen to get accepted should the need arise. They have been instructed by relief agencies to attempt to follow the previously mentioned CDC guidelines about social distancing and handwashing, but this is incredibly difficult in the camps. Tents are small, and many people have to sleep next to each other. Water stations and bathrooms are few and far between. As coronavirus tests are barely accessible to US citizens, finding one would be challenging for someone in the camps.

Discussions of this contagious virus have created anxiety for any empathetic person. Despite the grim reality, there are some positive efforts taking place. GRM is currently working on a twenty-bed field hospital near the Matamoros camps, although they may face more challenges as United States volunteers may not be allowed to travel there. Al Otro Lado, a legal services organization, and the Refugee Health Alliance have distributed medication and additional hand washing stations to many asylum-seekers. While there are few suspected cases of COVID-19 at the camps as of yet, these actions could be crucial in containing the virus should an outbreak occur. It’s important to remember wise words by Richard Blewitt, UN representative for the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, “At this time we need global and local solidarity and compassion with all those affected by COVID-19, wherever they live.”