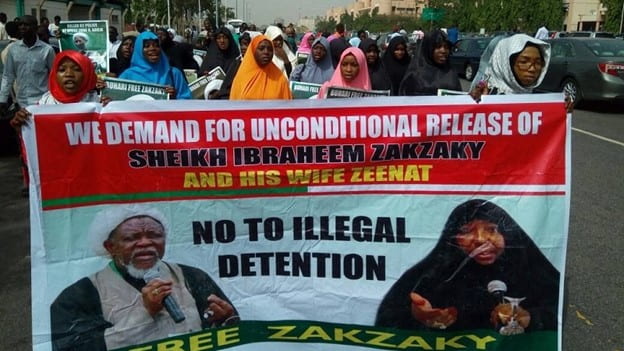

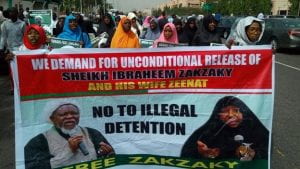

In Nigeria, the Shia Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) has been the victim of brutal police force at its ongoing peaceful protests that started in 2015. Recently, the religious group has been categorized as a terrorist group by the Nigerian government, which is an explicit violation of the Muslims’ human rights. On December 12, 2015, Sheikh Ibrahim el Zakzaky and his wife Zeenat, were arrested by the Nigerian Army and handed over to the Department of State services following a bloody clash between the soldiers lead by Lieutenant General Tukur Buratai and members of the IMN. The clash occurred in Zaria, Kaduna State, and since the arrest of the leader of the IMN, the followers of the movement have been protesting for the release of their leader. In light of the multiple protests, the Nigerian government issued a ban on the IMN on July 28, 2019, after a protest in the capital, Abuja. The ban was ordered by a Nigerian court which ruled the activities of the Shia IMN as “acts of terrorism and illegality.”

What is the Islamic Movement of Nigeria?

Introduced by Sheikh Zakzaky in the 1980s, the Islamic Movement of Nigeria (IMN) is a Shia minority sect with close ties to Iran. The sheikh visited Iran and was inspired by its revolutionary movement where the Iranian Pahlavi dynasty was replaced with an Islamic republic led by Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini. Zakzaky created his own sect in Nigeria known as the Islamic Movement of Nigeria and has approximately four million followers located in northern Nigeria. They are separate from Boko Haram, an group of Islamic Nigerians who use violent means to spread their influence, something that Zakzaky and IMN members profusely denounce. The Shia IMN, like Boko Haram, sees the secular state as evil and wants an Islamic state based on sharia, or Islamic law. Their movement calls for the rejection of the Nigerian Constitution and encourages a revolution that focuses on enlightenment.

The Abuja Protest

On July 22, 2019, the Human Rights Watch reported that the Nigerian police fired unlawfully at a peaceful protest led by the IMN in Abuja, the capital of Nigeria. At around 12:30 p.m., thousands of protestors marched toward the Federal Government Secretariat to register their grievances, particularly regarding the ailing health of their leader, Sheikh Ibrahim el Zakzaky and his wife. Mohammad Ibrahim Gamawa, a member of the Resource Forum of the IMN group, reported that as the protestors approached the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, the Nigerian Police Force opened fire and threw teargas at them. Eleven protestors, Channels Television journalist, Precious Owolabi, and Deputy Commander of Police, Usman Umar died. The government of Nigeria claimed the IMN was responsible for the deaths of the journalist and police officer, hence the ban being issued six days later by a Nigerian court.

This protest was not the first one that resulted in deaths though. Nigerian authorities have used excessive force against the minority group since 2015. On December 12, 2015, the police used brutal force on the IMN’s street procession in Kaduna to allegedly clear the way for the army chief’s convoy, resulting in 347 members dead and several arrested, including the leader and his wife. Rather than holding the police accountable, the Kaduna State prosecutors brought charges against 177 IMN members for the death of Corporal Yakuku Dankaduna – the only military casualty at Kaduna. Several more examples like this exist, but the Shia Muslims have not ceased their nonviolent protests for the release of their leader.

The Ban

Justice Nkeonye Maha issued the ban order on July 26, 2019, declaring the activities of the Shia IMN as “acts of terrorism and illegality.” The order was declared after an ex parte hearing, the application for which was filed barely 72 hours after the Abuja protest by the Attorney General. The Islamic Movement of Nigeria was the sole respondent to the application, but it was not represented by a lawyer since this type of hearing is issued without the responding party being made aware of it. In her ruling, Justice Maha ordered the Attorney General of the Federation to publish the order in the official gazette and two national dailies.

How is this a human rights violation?

Anietie Ewang, the Nigerian researcher at the Humans Right Watch, says that the court ruling “threatens the basic human rights of all Nigerians,” and the government should “reverse the ban, which prohibits the religious group’s members from exercising their right to meet and carry out peaceful protest.” Both the Nigerian Constitution and international human rights law prescribe the rights to freedom, association, and expression, which the proscription violates. Under international law, no restrictions can be placed on these rights unless it is provided by law, serves a legitimate government purpose within a democratic society, and is necessary for attaining that purpose. Allegations of criminality do not present legitimate grounds to proscribe the activities of a religious group, according to Ewang. She also suggests that the ban may foreshadow a worse security force crackdown on the IMN, having dire human rights implications throughout Nigeria.

Why has the IMN been protesting since 2015?

The obvious reason is the arrest of Sheikh Zakzaky and his wife, Zeenat. Upon their arrest, the couple was handed to the Department of State Services (DSS), and they remained in DSS custody for over two years without charge. In April 2018, the Kaduna State Government filed eight counts against the leader and his wife. The charges include killing Corporal Yakuku Dankanuda who died during the December 2015 bloody clash at Zaria. The protestors have not only been vocal about the allegations but also the health of the sheikh and his wife since they also sustained injuries in the Zaria clash.

What has happened since with the case?

As of September 29, 2020, the Kaduna State High Court dismissed a no case submission application submitted by Zakzaky and his spouse. Justice Gideon Kurada said it was premature to rule on the application to quash the charges against the defendants. The case has been adjourned till November 18 and 19, 2020, where the prosecuting counsel will present evidence and continue the trial. The charges are eight counts including culpable homicide, unlawful assembly, and disruption of public peace.

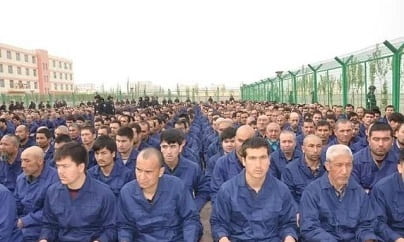

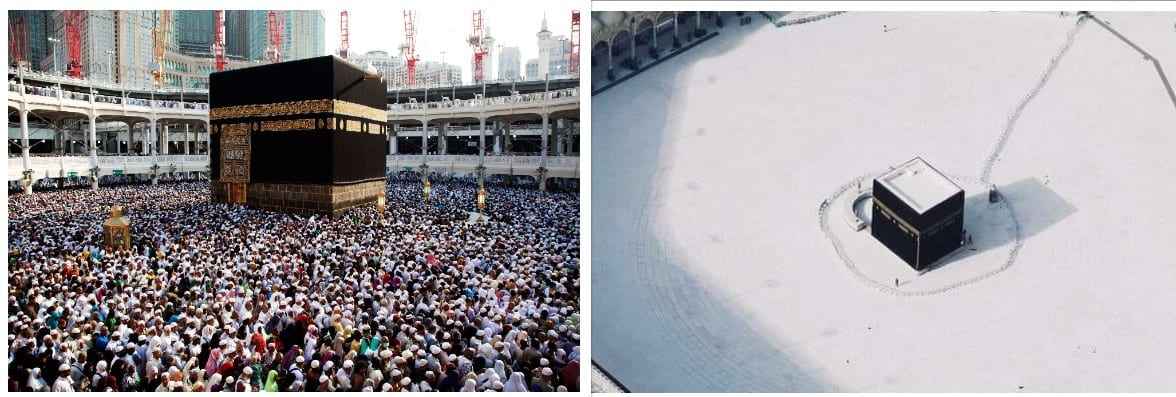

The frustration of the Shia Islamic Movement of Nigeria is understandable. They are simply asking to practice their religion in a peaceful manner. The clash between Shia and Sunni Muslims is prevalent in other parts of the world as well, but Islam preaches brotherhood and unity. All Muslims are considered a part of the global Ummah, or community. The unjust bloodshed of these people will not resolve any problems, nor will it bring peace to the ongoing conflict in Nigeria. It is time for the human rights of the Shia Islamic Movement of Nigeria be restored and their leader be acquitted.