Sex Education in the United States

In the United States sex education has historically been underfunded and often used as a tool to shame people for their sexuality. Currently, only 29 states in the United States mandate sex education; however, this still does not ensure that children are taught medical sex education in school. In fact, 37 states within the United States require abstinence to be taught as the only way to prevent sexually transmitted diseases and unwanted pregnancy. Even worse, up until April 2021, seven states in the South prohibited educators from discussing LGBTQ+ identities and relationships, which further stigmatizes youth and puts them at a higher risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases. Currently, now that Alabama has passed a new bill which removed homophobic language forbidding schools from teaching LGBTQ+ sex education, teachers are able to create sex education curriculum as they please, as long as parents are sent an overview of the curriculum and agree to let their children learn said material.

How U.S. Sex Education Policies Measure Up to the ICPD

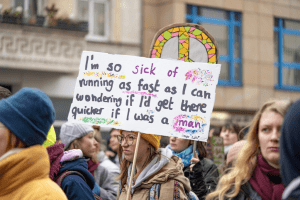

According to the 1994 Cairo International Conference on Population and Development (ICPD), “ the objective to achieve universal access to quality education, underlines that gender-sensitive education about population issues, including reproductive choices and responsibilities and sexually transmitted diseases, must begin in primary school and continue through all levels of formal and non-formal education to be effective.” The ICPD further notes that “full attention should be given to the promotion of mutually respectful and equitable gender relations and particularly to meeting the educational and service needs of adolescents to enable them to deal in a positive and responsible way with their sexuality.” When looking at the rights set forth by the ICPD, it becomes clear that the United States is failing their youth populations and exposes them to unnecessary risk by refusing to inform them of the dangers that come with unprotected sex. By not requiring sex education, the United States also fails to inform youth of preventative measures they can take to ensure the utmost safety and consensual enjoyment between parties. This lack of education has not only resulted in a multitude of unwanted pregnancies and an overflooded foster care system; but has led to thousands of people, especially in the South, contracting chronic disease and illness that will impair them for the rest of their lives as well.

Women’s Healthcare in Alabama: The Dangers of Improper Sex Education

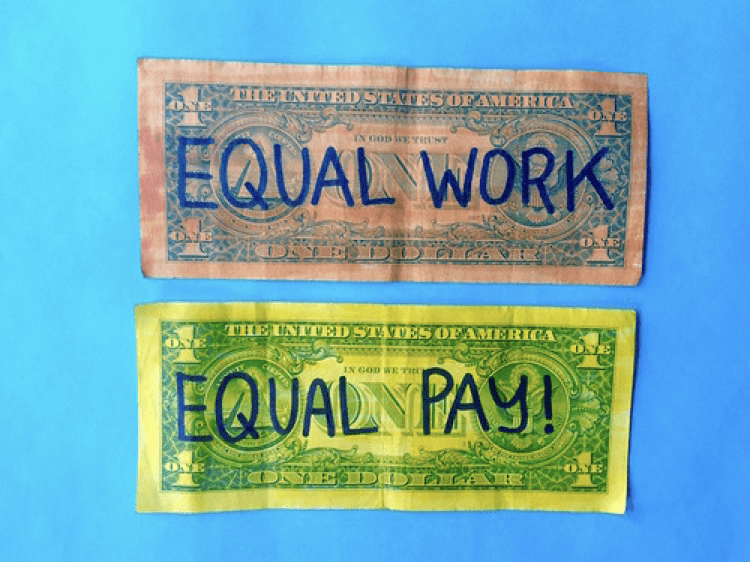

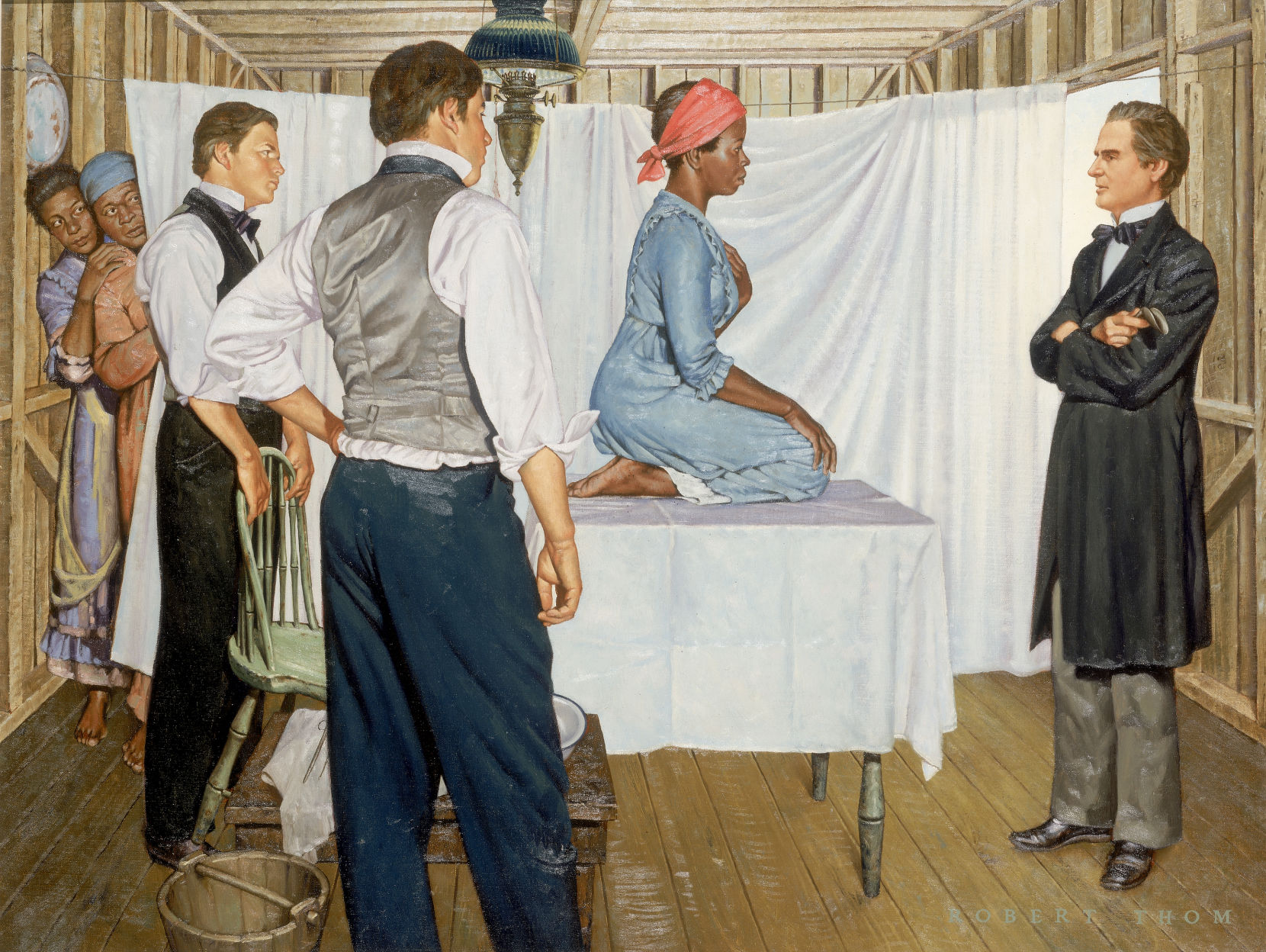

While the United States as a whole has failed its constituency by refusing to mandate sexual education to be taught in schools, the state of Alabama stands as a paradigm for just how dangerous a lack of healthy and inclusive sex education can be. According to Human Rights Watch, the lack of sex education in Alabama has led to relatively high mortality rates. These “mortality rates are higher for Black women, poor women, and those who lack access to health insurance.” In fact, according to the CDC, in 2017, Alabama was among the top five states in the country in terms of the highest rate of cervical cancer cases and deaths, and “Black women in Alabama are nearly twice as likely to die of the disease as white women.” While multiple factors are contributing to this alarming statistic, Human Rights Watch found the following issues to be catalysts for these poor outcomes in Alabama: “shortage of gynecologists in rural areas, prohibitive transportation costs often required to travel to see a doctor for follow-up testing and treatment, and Alabama’s failure to expand Medicaid to increase healthcare coverage for poor and low-income individuals in the state”. By refusing to provide access to healthy sex education, Alabama has left thousands of women without the proper knowledge that is necessary to lower the risk of cervical cancer.

The Current State of Sex Education in Alabama

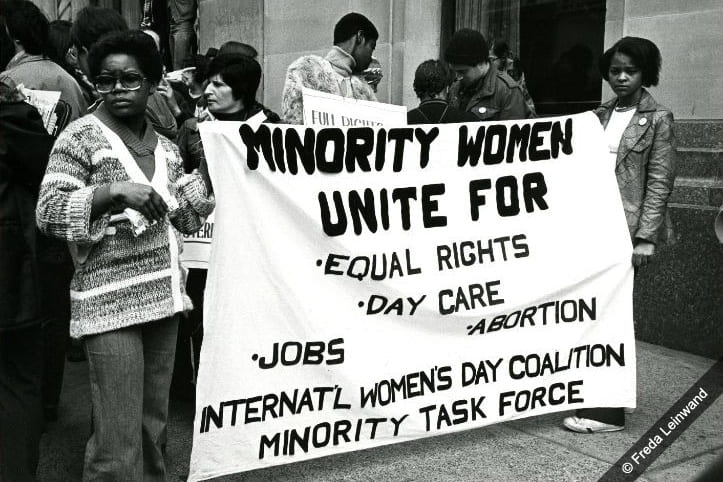

In Alabama, the current state code claims that abstinence outside of marriage is the “social norm”. By making non-marital sex an abnormality, the legislatures have shown that they have no interest in providing education to youth who may break the “social norm”. Moreover, in the past, Alabama code emphasized that sexual curriculum had to be presented in a “factual manner and from a public health perspective, that homosexuality is not a lifestyle acceptable to the general public and that homosexual conduct is a criminal offense under the laws of the state”. By painting non-heteronormative orientation as “criminal” Alabama consciously stigmatized members of the LGBTQ community for decades, which put them at a higher risk of contracting a chronic disease. In fact, according to SIECUS, Alabama ranked fourth in the nation for reported cases of chlamydia, gonorrhea, and syphilis in youth aged 15-19. Yet, thanks to activists and constituents voicing their concerns, the Alabama legislature has now removed said discriminatory language from their sex education bill. However, there is still a large amount of work that must be done to further advocate for proper, medical sex education to be provided to students.

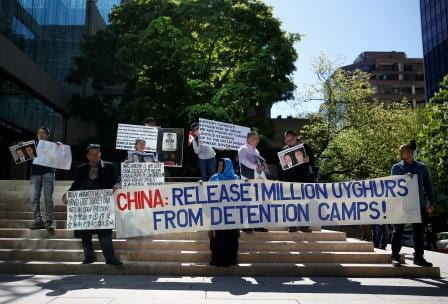

Ways to Get Involved

Thanks to the work of activists, legislatures, and constituents alike, Alabama’s laws have been updated so that they no longer criminalize LGBTQ+ individuals within the states schools’ sex education curriculum. Yet, the work is not over, and schools are still able to refuse to educate students on safe sex practices for non-heteronormative relationships, as long as parents of students consent to the curriculum proposed by staff. This continuation of the lack of medical sex education in our school systems is still leaving children vulnerable to ignorance, and exacerbating the current health issues which are prevalent amongst marginalized groups, especially within the South. Certain organizations, such as the Alabama Campaign for Adolescent Sexual Health and Advocates for Youth Sex Education, are currently advocating for proper sex education. If you are interested in getting involved, sign up to be an advocate for proper seed education through AMAZE, or with WISE (Working to Institutionalize Sex Education), to help aid in the fight for proper sexual education for our youth. Furthermore, if you would like to learn more about the rights of LGBTQ+ individuals and current issues within the LGBTQ+ community, then click this link.