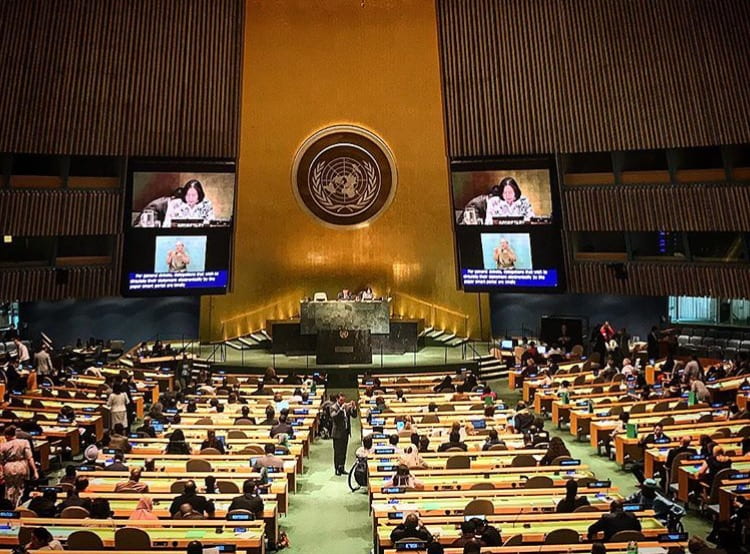

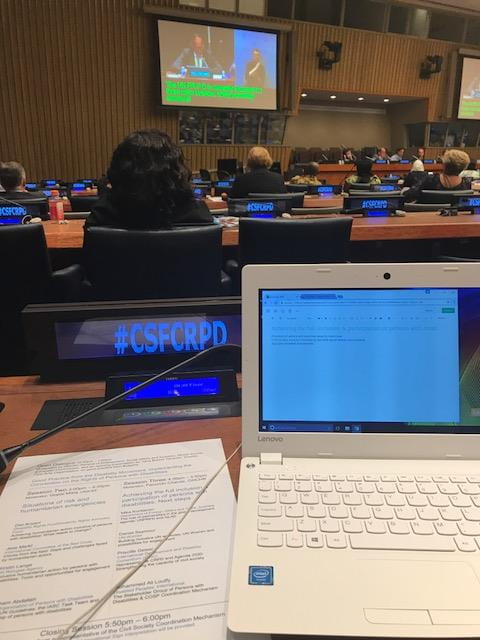

Recently, members from UAB’s Institute for Human Rights (IHR), including myself, had the opportunity to visit the United Nations (UN) in New York City for the 11th Conference of States Parties (COSP) on the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD). The CRPD is an agreement that details the rights of persons with disabilities (PWD) with a list of codes for implementation, where both states and disabled people’s organizations (DPOs) are suggested to coordinate to fulfill such rights. Currently, the CRPD has 177 ratifying parties, with the United States being one of the last to have not ratified it, although it was modeled after the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), the cornerstone for disability rights in the U.S.

I had the opportunity the serve as rapporteur for Round 3 of the General Debate, witnessing representatives address issues such as education and employment barriers for PWD in rural Afghanistan, India’s concern about the treatment of women and girls with disabilities, Malta’s 20 million Euro dedication to programs and organizations for PWD and Peace 3 Foundation describing how climate change disproportionately endangers PWD. Additionally, I attended many side events that covered topics such as the Voice of Specially Abled People (VOSAP) phone app, barriers to political participation in the Middle East and North Africa, and the first Regional Report of the Americas. The side events were less formal and engaging because the audience was welcomed to participate by sharing their thoughts and expertise, allowing coalition building to take place.

Amid this experience, there were a few important lessons learned. First, there is an enormous push for inclusive education, as opposed to special education, which values PWD’s contributions, equips them with essential skills and validates their societal presence. This approach would allow PWD, namely children, to learn and grow with their peers. Secondly, many nations are not responsibly addressing psychosocial disabilities which are clinical conditions/illnesses that affect one’s thoughts, judgments or emotions. Many countries have legislation that prevent people with an “unsound mind” from full participation in society, which doesn’t relate to one’s acts, but only their character. This stigmatizing approach effectively criminalizes their disability status, possibly resulting in forced institutionalization that separates them from loved ones and their community. Finally, there are countless people worldwide addressing disability rights. In the U.S., it seems disability rights are in the background, while other justice causes get most of the attention; however, I am confident that persistent coalition-building between justice organizations, especially in our impassioned political climate, will change this narrative, much like the collaborations built through the CRPD.

I want to use this blog as an opportunity to address an issue that has personal sentiments and speaks to my second point, stigma toward people with psychosocial disabilities (PWPD). Given my experience working in homeless shelters and having someone close to me who was institutionalized for their schizophrenia diagnosis, I believe there is a cultural disparity in how we talk about psychosocial disabilities because, on many occasions, they are addressed from a criminal and/or deviant lens, often devaluing the person(s) being addressed. According to the Mental Health and Human Rights Resolution of the Office of the United Nations High Commissioner for Human Rights, PWPD are defined as those, “…regardless of self-identification or diagnosis of a mental health condition, face restrictions in the exercise of their rights and barriers to participation on the basis of an actual or perceived impairment.” Psychosocial disabilities differ, meaning they are capable of being episodic, invisible and/or not clearly defined (e.g. depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and schizophrenia). Also, psychosocial disabilities are subjected to a medical narrative that arguably benefits mental health industries more than consumers.

Two years ago, during the 9th COSOP to the CRPD, Paul Deany (Disability Rights Fund Program Officer) claimed psychosocial disabilities are addressed in many countries through Western-influenced legislation that is separate from other disabilities, streamlining the establishment of psychiatric institutions that undermine fundamental issues for PWPD such as workforce participation, health care and political/rights. Therefore, we cannot view this concern as being exclusive to poor, underdeveloped nations because psychosocial disability stigma in rich, developed nations have fed this narrative and still have a prominent effect on PWPD. Although, to achieve collaborative global efforts that empower PWPD, supportive mental health policy must, first, be endorsed on the homefront. For example, political turmoil in the U.S. has contributed to recent events geared to strip health coverage from millions of vulnerable Americans. These efforts clearly demonstrate political incompetence of the mental health discussion at-large and confess to a larger narrative that admits power doesn’t always equate to knowledge and global leadership must be justified, not assumed.

Although many countries have enacted and enforced rights for PWPD, other countries are falling behind. For example, in Indonesia, roughly 18,000 people are forced into pasung, the practice of shackling or locking one in a confined space. Although pasung was banned by Indonesian authorities in 1977, families and healers continue to exercise this inhumane practice because they believe evil spirits or immoral behavior induce such disabilities. A similar practice in Ghana, at Nyakumasi Prayer Camp, was scrutinized last year, followed by the release of 16 people and the country’s Mental Health Authority claiming they would begin properly enforcing the shackling ban put into law in 2012. Such treatment of PWPD clearly impinges the Universal Declaration for Human Rights (UDHR), a watershed document for global peace, by violating commitments to end “cruel, inhuman or degrading treatment or punishment” (Article 5) and equal protection before the law without discrimination (Article 7).

To someone living in the modern U.S., such treatment seems unimaginable. However, past images of PWPD experiencing isolation and inhumane treatment inside the asylum walls are now echoed from a different, yet similar, perspective. During the mid-20th century, the U.S. underwent a period of deinstitutionalization which saw the closing of large state institutions that harbored PWPD. Largely due to the advent of the antipsychotic drug Thorazine, thousands of people were discharged from state mental hospitals and the shutting of such doors soon followed. However, the following decades have seen an influx of criminalizing PWPD, leading to their incarceration, where jails and prisons now serve as some of the nation’s largest de facto mental hospitals. This series of events, which moves PWPD from one total institution to another, undermines the liberation narrative of deinstitutionalization by continuing to segregate PWPD from their families and communities. As a result, this misfortune contributes to the current crisis that has seen the U.S. prison population increase by 408% between 1978 and 2014.

These appalling scenarios underscore a comment made by the representative of Kenya, during my visit to the UN, who insisted that policy cannot solely enforce human rights because programming must also be present to guide that path. Since 2007, Users and Survivors of Psychiatry in Kenya, a DPO, has not only influenced legislation that expands the rights of PWPD, but also organizes participatory public education programs through various media outlets, challenging stigma and misconceptions. On the other side of the Atlantic, in Connecticut, the Center for Prisoner Health and Human Rights works with local governments, universities and health systems to ensure recently incarcerated people access health care and insurance. Many of the individuals receiving such care access health-related goods and services to treat psychosocial disabilities that could’ve influenced or been a byproduct of their incarceration. Looking forward, this is the type of advocacy and programming that needs to be highlighted so it can be shown that good governance, particularly through the CRPD and ADA, is possible.