When I studied abroad in Spain, I had many discussions with my host family comparing the United States and Spain. These conversation topics ranged from politics, social expectations, and the weather. One topic that my host mother was especially interested in is the American health care system in comparison to the Spanish health care system. Spain has a universal health care system while still allowing private insurance whereas the United States has purely private insurance. Neither system is perfect. However, as the Covid-19 crisis continues to progress it is important to understand how the crisis brings to light the many issues with the American health care system.

It is a well-accepted fact that the United States was significantly less prepared for the impact of Covid-19 than most other developed countries. By any metric of pandemic preparedness, America is significantly behind the rest of the developed world in regard to medical supplies. The country has a severe lack of health care infrastructure within the system; even before the international pandemic, the United States had fewer doctors and hospital beds than the majority of other developed countries. The United States lacks in the number of doctors per capita with 2.6 doctors per 1,000 people. The comparable country average is 3.5 per 1,000 people, which shows just how behind America is. The United States also has fewer hospital beds per capita than the majority of other developed countries. To make matters worse, America has some of the highest rates of unnecessary hospitalizations. These are hospitalizations of patients with chronic conditions that have preventable treatment, making it unnecessary for the patient to be hospitalized. With a pandemic such as Covid-19, these unnecessary hospitalizations are diminishing. However, in the beginning of the crisis within the United States, unnecessary hospitalization significantly slowed down the efficiency of the health care system in caring for Covid-19 patients.

An important trend in the preparedness of the United States for Covid-19 is that the United States, with a private health care system, was noticeably less prepared than countries with universal health care systems. It is true that universal health care is not the perfect response to pandemic emergencies like Covid-19. This is shown by Italy, a country who has a federalized national health insurance program. Italy still needed to lock down and for a while had the highest case and death rate than any other country. However, countries like Italy with universal health care were able to begin recovery and slow the spread of the virus much quicker than those without.

As health providers have been working tirelessly to make the necessary changes to care for Covid-19 patients, private health insurance companies have been making very few changes to their processes. One system health care providers have been implementing is telemedicine, a program that allows patients to securely consult with their health care providers virtually therefore easing the burden on the infrastructure of the hospitals. Despite President Trump expanding provisions on telemedicine, private health companies are not required to pay health systems for telemedicine. At the same time, while some insurance companies have waived some Covid-19 related costs, out-of-pocket expenses are not waived resulting in patients needing to pay thousands of dollars. To put these costs in perspective, in 2018 the average amount for a patient covered by private insurance admitted to the hospital for a respiratory condition similar to coronavirus was $20,000. Additionally, as hospitals across the country prepared for an influx of Covid-19 patients, stable patients without the virus were forced to stay in the hospital beds. These patients, who should have been moved to a rehab facility or released, were taking up unnecessary space due to private insurance companies taking multiple days to authorize the next steps for each patient. This has been a known delay in hospitals before the pandemic but now it is a delay that has dire consequences.

Quite possibly the biggest problem in the American health care system is cost. This problem is unique to the United States. Citizens are required to pay higher out-of-pocket costs than those in most other countries, leading Americans to forgo their health care in order to save money. Reports have shown that 33 percent of Americans reported a cost-related barrier to receiving care. This is in comparison to the 7 percent who reported the same in Germany. In 2019, a study showed that 33 percent of Americans also reported postponing medical care due to the cost of that care. It is only in the United States that citizens are risking thousands of dollars in order to seek help in a medical crisis like the one posed by Covid-19. A major concern across the world is that Americans will not seek care for corona symptoms due to the high costs of healthcare in the United States and the high amount of people without insurance in the country. This will spread the disease significantly faster than officials within the country would like to believe.

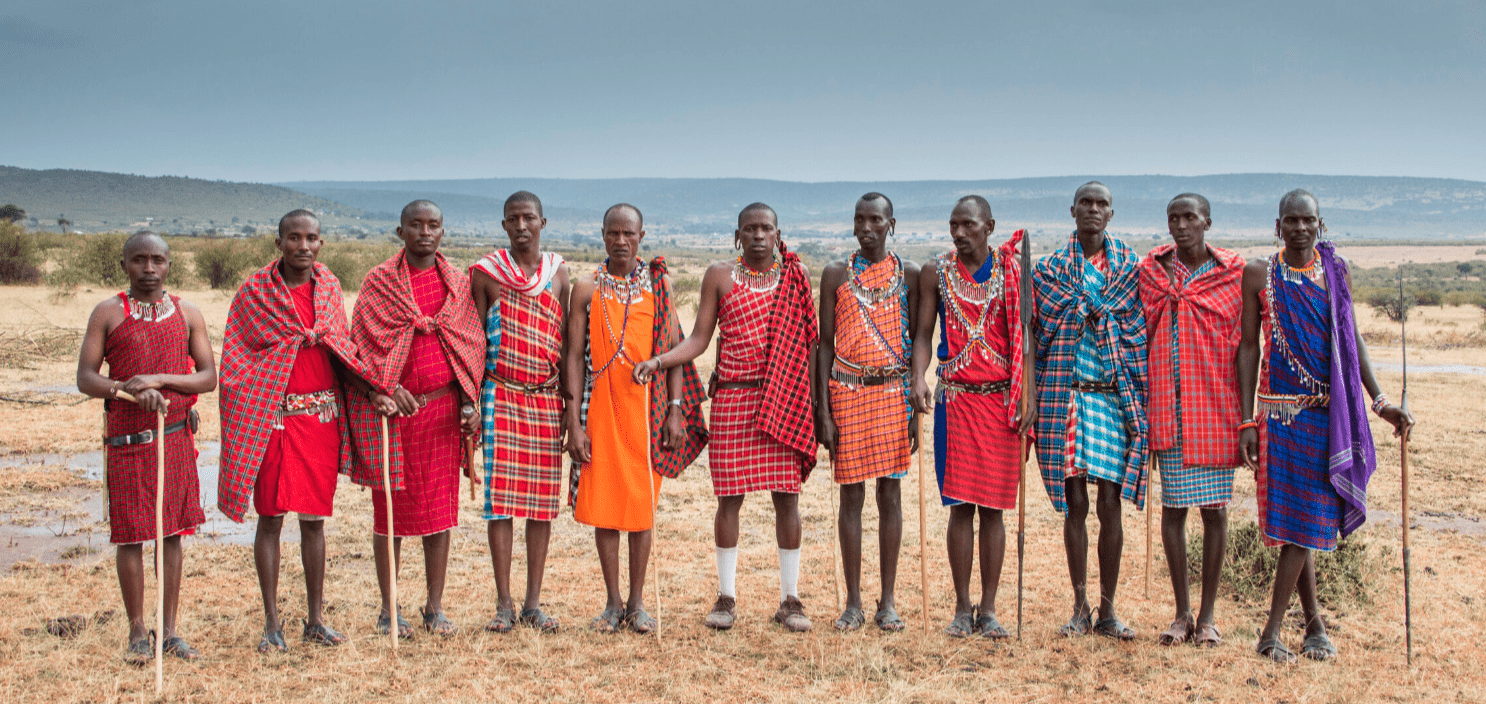

As the Covid-19 cases rise in number across the country, an unusually high number of African Americans in the United States have been infected with Covid-19. This news, while terrible, is unfortunately not shocking and highlights the many racial inequalities in the health care systems. Coronavirus does not have a racial factor but the structural racism within the American health care system is evident. African Americans are over-represented in many essential workplaces making the population more at-risk than other populations. At the same time, African American populations are less likely to have health insurance coverage leading to a disproportionate number to not receive the necessary help from the health care system. There also exists a racial empathy gap that disproportionately affects African Americans and Hispanics within the United States. A racial empathy gap is when medical professionals show less empathy and sympathy to African American patients who are experiencing pain. Human rights workers have been working on mandatory reviews to ensure that health workers are providing an equitable form of treatment for minority patients. However, due to a bias developed and enforced by societal constructs of different races, there exists a higher risk for minority populations within the American health care system.

A few examples of problems within the American health care system that have been exacerbated by Covid-19 are highlighted above. While officials within this system and within the government must work to make necessary changes, it is also important to recognize the lifesaving and tireless health care workers who work within the imperfect system. Covid-19 has shown the country how necessary health care workers are. Nurses, doctors, surgeons, and so many other health care providers have dedicated an immense number of hours to fighting Covid-19. These individuals who are working to save lives within the corrupt health care system are extremely important and we must recognize their hard work while we work to make the system fairer and more equitable.