During the 2016 election, I was 17 years old, meaning that I was too young to vote and just old enough to be very frustrated by this barrier. Now, for the 2020 election, I am excited to cast my vote in my first presidential election and have thrown myself into learning as much as I can about domestic and international politics. Through this process, I have begun to recognize political trends and waves. Idealism has shifted and flowed along the political spectrum throughout history. Recently, many countries across the world have taken a conservative shift in their political maneuvers and with their elected officials. What makes this shift slightly different is the large rise of nationalism across many countries.

What is Nationalism?

For a definition, people with nationalist leanings dislike the rise of globalization in social structures and political institutions. There is a rather large emphasis on putting national interests and needs before global ones, hence the name “nationalism.” Nationalism is understood to be focused on the ‘cultural unit of the nation.’ However, for a significant portion of history, one’s political leanings were not reliant on national boundaries. This changed in Europe after the Protestant Reformation. The state became more reliant on the people who resided within the nation instead of outside forces like the Catholic Church. Soon, nationalism and self-determination became integral parts of the view of democracy.

Nationalism is the strong support of a country, akin to patriotism. Self-determining nationalism refers to a desire for a state rooted in a self-identity. This is the basis of white nationalism, the desire for a white state. Some people may believe that nationalism is rooted in the American story and that without it the Constitution might not even exist. However, realistically, racism and racists in general feel represented and validated by Donald Trump’s form of nationalism. The campaign of “America First” and “Make America Great Again” are set in a very distinctively nationalist direction. The primary issue with this stance is that Donald Trump’s definition of “American” excludes quite a few groups of people who live in the United States. This is called ethnonationalism. A few examples of the ethnonationalist tactics employed by Donald Trump and his party include the creation and fascination with the border wall between the United States and Mexico, the Muslim ban, and the active separation of families along the Mexican border, among many others. Similarly, a rise in white nationalism has occurred, encouraged by the Donald Trump base.

Nationalism Throughout History

During the Industrial Revolution, it became apparent that aspects of a shared identity, such as shared literacy in a single language, would be important to a nation’s success. Thus, the assimilation of groups outside of the collective norm of the country became perceived as a top priority. This assimilation happened through civic institutions but also through ethnic cleansing, war, and other violent methods in order to completely wipe out any cultures or traditions considered to be “different” from the nation’s own. In the 1900s, there was a separation created between the ideas of ‘liberal capitalism’ and ‘nationalist democracy.’ This history lesson is to depict the ebbs and flows of nationalism throughout history. It is not uncommon to witness a resurgence of nationalism; however it is important to understand the negative consequences in order to navigate the resurgence in the most effective way for all groups.

Benefits and Dangers of Nationalism

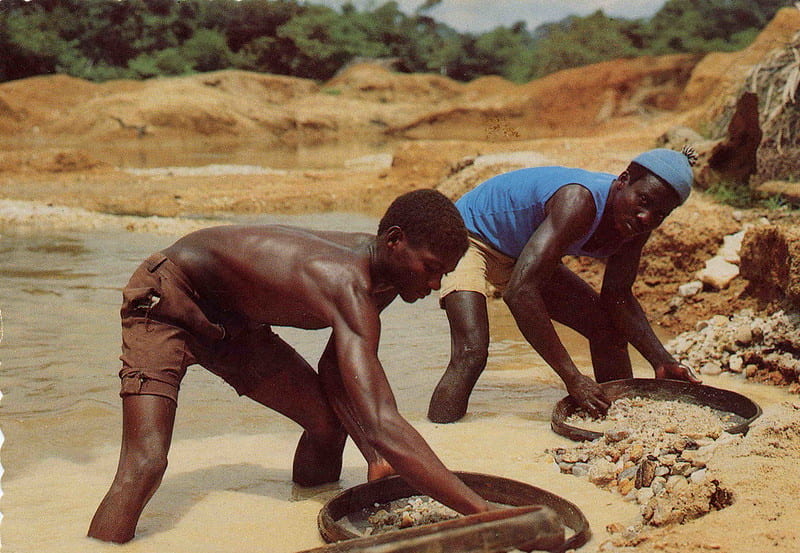

Nationalism can be utilized for development. Throughout history, nationalism can be attributed to a rise in the buying and selling of domestic products, recruitment in the military, and general patriotism. The idea of a shared identity connected to a country is a motivator among citizens. In Korea and Taiwan officials were able to implement the Japanese inspired top-down nationalist model that greatly encouraged growth. However, nationalism can also encourage exclusion and competition. In Europe, imperialism and colonization were often justified by nationalism. These were two techniques employed by western countries to overtake and completely control countries in Africa and in the Asia, the extremely negative consequences of which are still being seen today. During World War II, Adolf Hitler employed nationalist techniques in order to secure his base and rationalize his tactics as in the best interest for Germany. Nationalist sentiment, seen as establishing one group to be the rightful citizens of a country, is dangerous in an increasingly globalized world.

Nationalism Across the Globe

After 2016, there was a large rise in nationalist sentiment across the world. Perhaps the most popular stage for this phenomenon was the United States with the election of Donald Trump, who ran on a nationalist platform with the slogan, “America First.” In Germany, the nationalist AfD party has become a major opposition party, and in Spain right-wing Vox has become prominent within the Spanish Parliament. Similarly, nationalist leaders have ascended onto the political stage in China, the Philippines, and Turkey. Nations are no longer made up of a single ethnic, religious, or language group. This increase in exclusionary nationalism that we are seeing could prove to be potentially very dangerous for the groups considered to be “outsiders.” It is important to understand the many different facets of nationalism in order to protect against the negative consequences it brings as these political leaders rise in popularity.