In the aftermath of Charlottesville, there has been national attention on hate and the fight against it. One must wonder where the line—if there is one—between free speech and hate speech; it does exist but it is a very fine line. The First Amendment protects citizens against government infringement upon speech but it does not explicitly protect against retaliation from private companies and universities. Since the protection of hate speech does not exist wholly under the First Amendment, employers fired several of the Neo-Nazis present at the Charlottesville rally.

I interned for SPLC on Campus this summer. It is the Southern Poverty Law Center’s campus outreach program. It aims to promote LGBTQ+ rights and racial, economic, and immigrant justice on college campuses and within local communities. It also advocates against hate crimes and bigotry. Charlottesville happened during my last week at the center. The live streams flooded social media and the positive collective response blew me away. Although the amount of hate disheartened me, I had hope because people were just as shocked as I was, and everyone I knew was condemning the hate while sending love and support to victims. There were solidarity rallies and protests promoting unity. There was also an increase in SPLC on Campus club registration.

SPLC on Campus began two years ago. Lecia Brooks, director of Outreach at the Southern Poverty Law Center as well as the Civil Rights Memorial Center, launched the program into full throttle. There are around forty-five active clubs in the States now with the staff for the program standing at only three people. These three people, including Lecia Brooks, Daniel Davis (the SPLC on Campus Coordinator), and Shay DeGolier (Outreach and Organizing Specialist) have been the foundation for these clubs. They fight hate relentlessly and push for more college students to do the same. College students have historically been a source of advocacy and activism; we still are. Here at UAB, the fight for equity, inclusion, and unity continue with student organizations like SPLC on Campus club, and Gender and Sexuality Alliance among others.

The Southern Poverty Law Center (SPLC), founded in 1971, tracks hate groups across the United States. As of today, there are 917 active groups. It is important to note that these groups are not just comprised of those on the far Right. What defines a hate group? The SPLC defines one as a group “[having] beliefs or practices that attack or malign an entire class of people, typically for their immutable characteristics.” (Hate Map, n.d.). Therefore, any organization that speaks out negatively about another about things they cannot or should not have to change–the color of their skin, their gender or sexuality, their religion, etc.

I have always heard the expressions, “If you can’t say something nice, don’t say anything at all” and “If they can’t fix/change it in a minute, don’t tell them.” The embedding of the first saying—along with the Golden Rule—took place in both the private and public spheres for me. Teachers, parents, and random posters with cats reminded me to treat others as I wanted to be treated. Everyone has heard at least some version of these clichés. Yet, when did we stop living by the childhood mantras we learned in kindergarten? So many people try to change things about others, and many do not do this kindly. If your friend notices something wrong with you, they might lean over and whisper, “Hey, you have some spinach in your teeth” but they would never say to you, “Hey, your skin is too dark.” It is interesting that hateful rhetoric is no longer taboo; it is mainstream.

A recent study reveals the very fine line between free speech and hate speech when employing the First Amendment. Supporters are quick to jump to the defense of someone saying something racist, often using free speech as a justification. However, with the removal of the targeted group identifier occurs, people rarely use the same defense. How far does the defense for free speech go? On a recent NPR Hidden Brain podcast, researcher Chris Crandall discusses a study he performed on this same question post-election, which revealed that people thought it was much more acceptable to speak out against groups that Trump had targeted in his speeches. The research proved some believe that if someone in a position of authority can use such speech with little to no retaliation, then it must be okay. Prior to the election, many withheld their bias for fear of punishment, look no further than the vilification of Mel Gibson or Michael Richards. Following the election, these barriers seemingly no longer exist, allowing a flood of prejudices to permeate our culture.

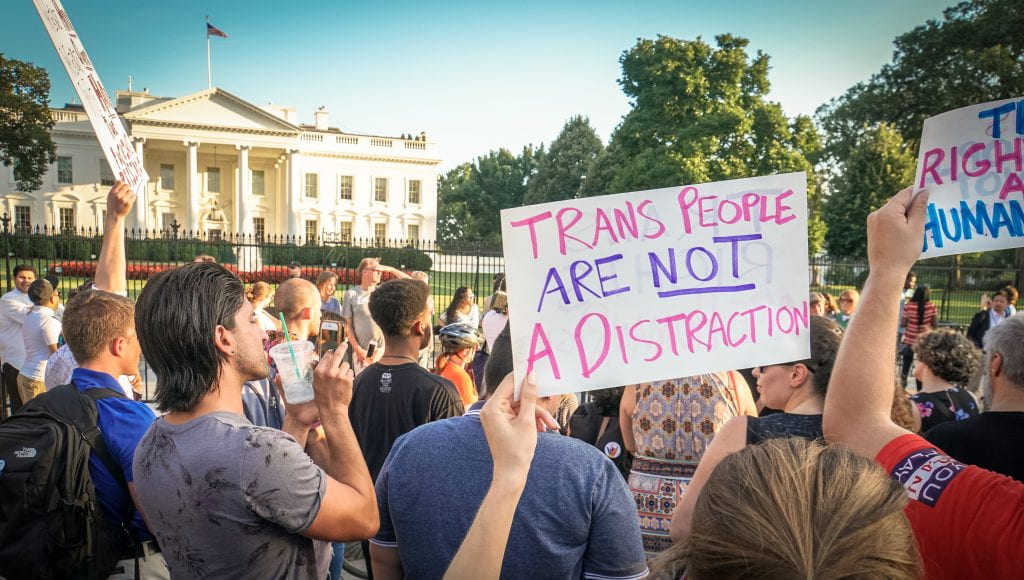

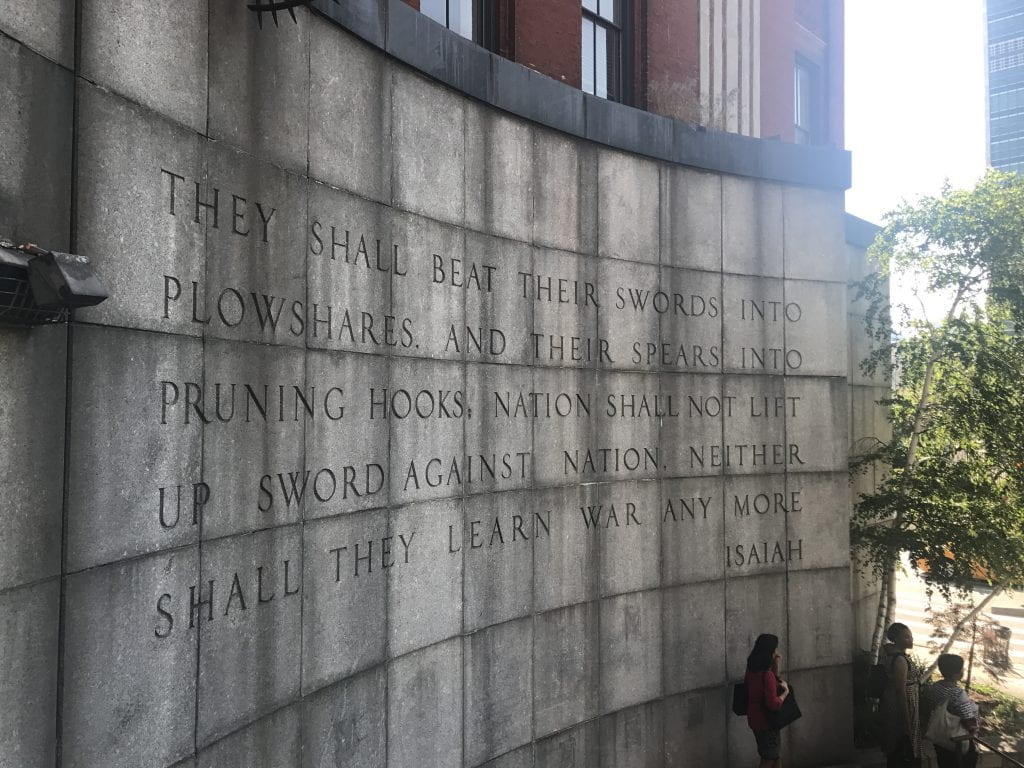

Remaining nonviolent in the face of such hatred is essential in overcoming it. Fighting fire with fire cannot solve this problem. In fact, there is evidence by counter protests that have ignited with violence. The entire fight for social justice is a figurative fight, fueled by protests, solidarity, unity, and participation. We cannot counter hate speech with more of the same rhetoric. You may wonder: What can I do to fight hate speech? My suggestions is get involved in groups that advocate against it. Reach out and get involved with human rights/social justice groups like SPLC on Campus, HRC, IHR, Amnesty International, and others. Hold protests and react nonviolently to such charged commentary. The most important thing to do is act. As I learned at SPLC, apathy is not an option.

The UAB Office of Diversity, Equity, and Inclusion will host a panel “From Protest to Academic Freedom: Free Speech, Hate Speech, and the First Amendment on College Campuses” tonight, Wednesday, September 20 at 6pm, Heritage Hall, room 102.

Here’s a more in-depth look at some steps you can take to prevent and fight against hate: https://www.splcenter.org/20170814/ten-ways-fight-hate-community-response-guide.

Caitlin Beard is a first-year graduate student from Hartselle, Alabama. She is pursuing a Masters of Arts in the Anthropology of Peace and Human Rights. Deaf culture courses and interaction with the Deaf World for her ASL minor ignited an interest in the field of human rights—specifically how it pertains to the Deaf and other oppressed groups.