A LGBTQ+ youth today may look at the world around them and think all hope is lost. It is understandable because the possibility of an entire community losing their civil rights at any moment is creating a looming fear. As human beings, we all come to terms with ourselves in our own ways; whether it is simply growing into yourself in order to find out who you are, or growing into someone you never imagined. The process of coming to terms with identity is completely different when your sexuality is not the “social norm.” Growing up, I felt scared of myself, and fearful of what the future might hold for people like me. However in 2015, when marriage equality became law, I thought to myself, “We are finally getting to a place where children will not have to grow up like I did.”

My story is not the same as every LGBTQ+ individual around the country, and certainly not across the globe. Every day, I wake up hoping that I do not hear of another story about a Matthew Shepard or Pulse Nightclub tragedy. To live as an open member of the LGBTQ+ community is to live in a constant state of worry. You may not always feel it, but the hum of it, however quiet it may be, still echoes through the back of your mind. It is a worry for your brothers, sisters, others of your community, and for yourself. This infringes upon our right to security, as we are afraid to be ourselves in public spaces. This fear even extends to private places because for many, our families are the main aggressors. For youths who suffer through the pain of oppression at the hands their family, there is never a true sense of peace.

I have faced discrimination throughout the course of my life. Based on my rumored sexuality, I experienced exclusion from many of things. It is a pivotal moment in one’s life when they choose to come out. It is a time that you accept all the ridicule, the torment, and the imminent threat of attack. I have emotional scars from peers and family that still haunt me to this day. Yet, what hurts me most is the look in another person’s eyes when they become aware of my sexuality; it is that look—from people whom I have never met—which is devastating. How can someone who knows nothing about me, judge me?

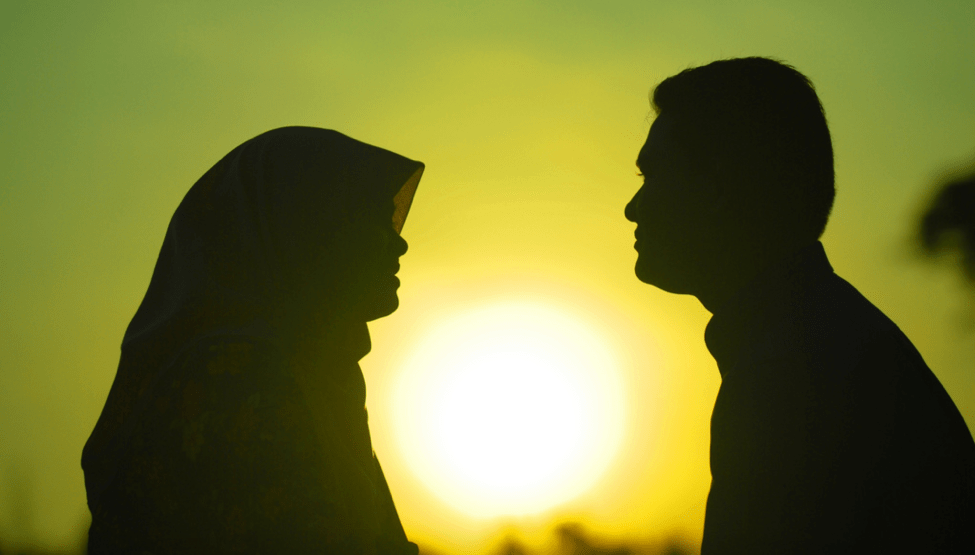

While the future for American LGBTQ+ youth seems frightening and uncertain, it is nothing compared to those of the LGBTQ+ community across the globe. A LGBTQ+ youth in the Middle East and Northern Africa has a different perspective based upon cultural experience and a belief that there is no hope and fear that there never will be–an upbringing filled with trials comparatively different to those I suffered as a youth. Living as an open member of the LGBTQ+ community in a Muslim country can potentially turn into a life threatening choice. Imagine that: telling your friends and family who you are, and then fearing that your life could end at that exact moment. That fear, no matter how far from home, affects us all.

Turkey is one of the few Middle Eastern countries where homosexuality is legal. Unfortunately, homophobia is still very prevalent so when a group of members from the community tried to initiate their own Pride festival, local authorities shot them with water cannons, rubber bullets, and sprayed them with tear gas. Across the Middle East, there are standing laws to persecute those of the LGBTQ+ community, including imprisonment for up to 10 years. In Ancient Egypt, being gay or lesbian was a godlike quality; however, in modern times, homosexuality is viewed as sin and punishable by death. When the White House went up in rainbow colored lights in 2015, the authorities in Saudi Arabia went on the hunt. Children face death around the country for “deviant” behavior by their own governments. A privately run school in Riyadh was fined $26,500 (in U.S. dollars) for painting the rooftop in rainbow stripes, and one of the administrators for the school was jailed for allowing such a “monstrosity”. Afghanistan banned the decorating of cars with rainbow stickers because it “may be misinterpreted.” In Iran, Yemen, and other Middle Eastern countries, many face execution for engaging in sodomy.

An assembly was called on in 2015 by the United States and Chile to bring light to the attacks on the LGBTQ+ community that are prominent in the Middle East, specifically by the Islamic State. Syrian refugees who fled their war-torn homeland spoke to the United Nations about what their life and the suffering they endured. One man admitted to hiding his sexuality his entire life, saying, “In my society, being gay means death.” Another man told of his witnessing of an al-Qaeda affiliated group taking control of his hometown and began torturing and murdering men that others thought to be gay. Cheering audiences attended the executions of gay men. Some men, tossed from building ledges, meet their death; however, for those who do not die upon impact, the hateful crowd stoned them to death.

Institutionalized discrimination is a prominent threat no matter where one may look across the globe.

In the south and in the US, we feel criminalized; in the Middle East, we are criminalized.

Being a part of a marginalized community has affected me in many negative ways, but also in positive ways. I feel a commonality with people I have never met and will likely never have the luxury of doing. As a part of the community, I am “branded in rainbow”, which is the most fulfilling feeling that I had experienced. I chose to take all of the negativity that surrounded me and channel it into positivity. This community and a shared experience has made me stronger, more confident, and allowed me to channel my anger by turning it into passion. As a member of this community, I implore you to become more accepting of the people around you, no matter where you may be from or what you may practice. It is powerful to feel human, and it is a feeling we all deserve.