by Delisha Valacheril

A jubilant celebration of color erupted as several indigenous leaders and activists gathered outside the courthouse adorned in tribal wear and brilliant headdresses to rejoice in the top court’s decision to rule in favor of their land rights. Dubbed the “trial of the century,” Brazil’s Supreme Court decided against a so-called cutoff date restricting Indigenous people’s claims to their traditional lands. Demarcation of ancestral lands is essential in preserving Indigenous human rights. By protecting these lands, indigenous communities can aid in conservation and preserve their cultural integrity. It is reported that 29% of the territory around indigenous lands in Brazil has been deforested, according to the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (Ipam). Now that the native people can access their roots, they can help preserve what is left. This decision also provides legal ramifications against land poaching or exploitation, which applies to several indigenous areas throughout the Amazon. Addressing historical injustices is a crucial step to ensuring that these communities can enjoy a more equitable and sustainable future.

Context

On September 21st, the Federal Supreme Court had to decide whether or not the native people’s right to their territories predated the Constitution of Brazil formulated in 1988. The Justices followed the precedent set up by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, which states that the right continues as long as their “material, cultural, or spiritual connection” with the land persists. This case has been brewing in the nation for quite some time. The dispute stems from Santa Catarina’s legal battle against the Ibirama-La Klãnõ Indigenous Land. The Xokleng tribe sought to regain their ancestral land from the state of Santa Catarina. The state used the “Marco Temporal” legal argument, which prohibited Indigenous Peoples who were not living on the land when Brazil’s current constitution was enacted in 1988 to apply for land demarcation. This is gravely prejudicial, given a significant part of the indigenous population was expelled and displaced during Brazil’s two decades of military dictatorship. Numerous tribal communities were killed and displaced due to that repressive system, which included the invasion of land, forced labor, displacement, and other human rights violations.

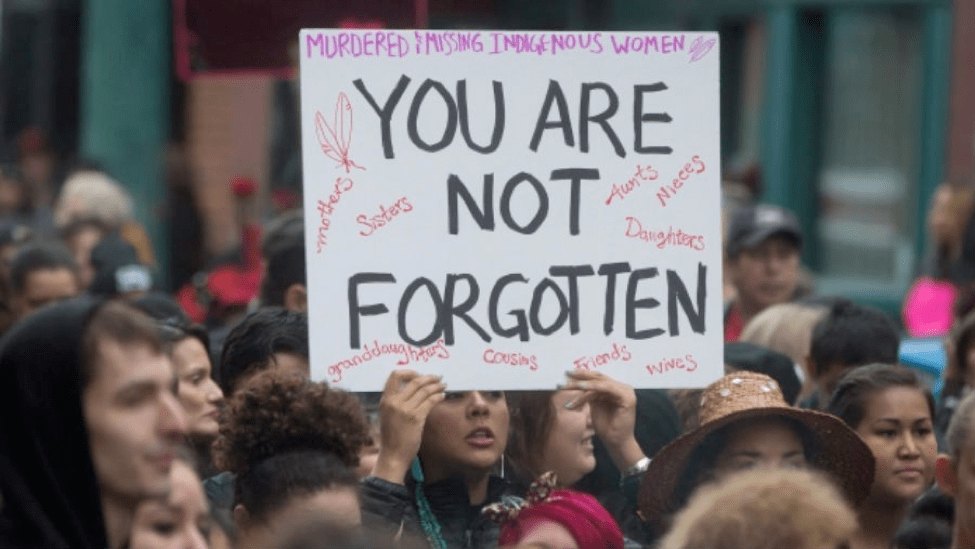

With this in mind, hundreds of activists have flocked to the capital, demanding respect for the rights that were stolen from them. These activists advocate for land traditionally occupied by indigenous people to be reserved for their perpetual possession. They are the natural owners of the land, so it should belong to them. They also argue that the natives can conserve the land much better than the local government. Traditional habits and customs of the indigenous are the most significant deterrent to deforestation. However, there are some critical opponents to this viewpoint. Individuals involved in the agribusiness sector and those on the far right are stronger than ever in National Congress, upholding the time limit principle. This decision opposes their farming interests because they want that land to grow their business. Currently, Indigenous reservations cover 11.6% of Brazil’s territory, notably in the Amazon. This area is rich in biodiversity, making it ideal for agricultural commodities. However, ruling against business interests could exacerbate violence against Indigenous peoples and escalate conflicts in the rainforest.

Historical Significance

The Xokleng, the tribe responsible for taking this case to the highest court in the country, was nearly wiped out by Italian settlers who were granted “uninhabited” land in the State of Santa Catarina by the Brazilian government during the 20th century. They were pursued by “bugreiros,” or hired hunters, who were sent into the forest to hunt down and exterminate the Amazon’s native inhabitants. After that mass extermination, how can the government uphold such a discriminatory precedent? The Xokleng are the rightful owners of the land because the Brazilian government forcibly removed them. Marco Temporal is a complete infringement on human rights. The tribe was almost decimated in the 1900s, and the law stated indigenous people living on the land past 1988 had a right to the land. Examining this from a historical viewpoint further illuminates the egregiousness of the situation. The Supreme Court of Brazil found this law inherently unfair because the same government that invaded indigenous lands could not decide on the legality of their land rights.

Conclusion

While this is a historic milestone for indigenous communities, the work is not over. Though land demarcation is critical in the pursuit to secure the rights of Indigenous Peoples, it does not, by itself, sufficiently protect ancestral land. We must hold the government accountable to implement an active, systemic policy that enshrines Indigenous rights from violence, especially violence committed by anyone who illegally trespasses into their territory. Additionally, they must have unhindered access to their territories. From a human rights standpoint, defending indigenous rights is critical because it resolves past wrongs, assures access to necessities, fights discrimination, and upholds justice, equality, and respect for the dignity of all people and communities.