The Problem

Indigenous women face overwhelming rates of violent crime, more than twice the amount of their non-Indigenous counterparts in the United States and 3.5 times in Canada. A 2016 study published by the National Institute of Justice revealed that approximately 84.3% of American Indigenous women have experienced violence against them in their lifetime and 56% of these women would become victims of sexual violence as well. In Canada, only 53% of Indigenous women’s homicides have been solved; drastically less than Canada’s national solve rate of 84%. That statistic becomes even more damning when we take into account that Indigenous females only make up 4% of Canada’s population, yet account for nearly one quarter of all homicide victims in Canada. For decades, Indigenous leaders, tribal governments and human rights organizations alike have called for national reviews in both Canada and the United States into the treatment of cases regarding Indigenous women. A publication from the US Department of Justice states that Indigenous female victims in the United States are far more likely to need services that aid survivors of such violence, but are the least likely group to have access to these services. The majority of Native American women will face physical or sexual violence in their lifetime, and more than a third will be unable to access necessary services after the event due to drastic disparities in access to healthcare and treatment by law enforcement. With each new set of data we have re-confirmed the existence of a plight sweeping through native communities, robbing women within them of their security, safety, and visibility.

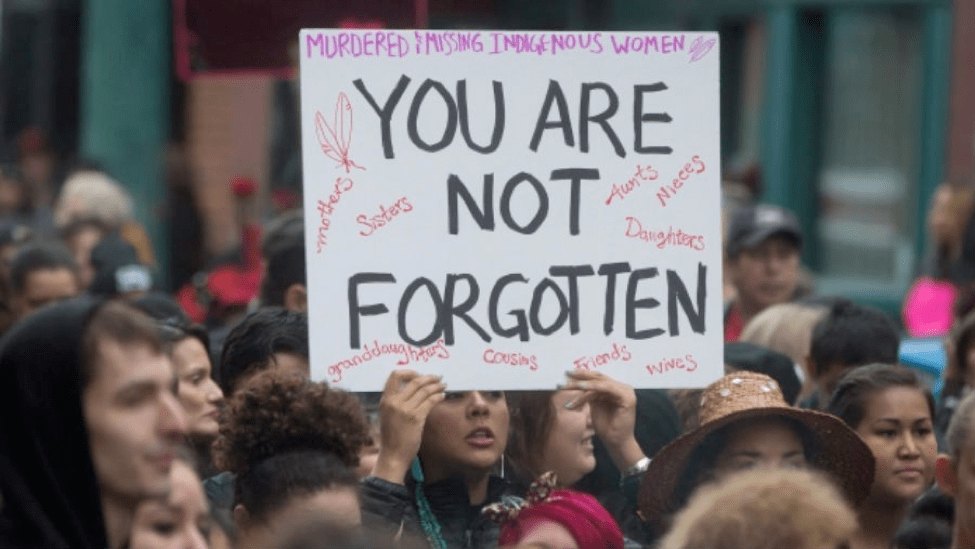

Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women (#MMIW)

In recent years, social media pushes have been made to raise attention for what is now known as “Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women”, a simple catchphrase encompassing decades of neglect from all channels that is now spearheading a movement for justice. This hashtag and social media campaign generates hundreds of thousands of interactions and impressions on social media every day, and brings attention to the individual stories of missing indigenous women or families of women lost to homicides that are still unsolved. However, indigenous women rarely get the national media attention that white women experience when they go missing; and when every minute and resource makes an empirical difference in the likelihood of that woman being found alive. A prior article from the Institute of Human Rights speaks specifically about the recent Gabby Petito case, and the disproportionate response of the American public for missing white women in comparison to women of color and indigenous women here. These drastically different responses only amplify the vulnerability of indigenous women.

It is horrific to think about a situation in which no one will come looking for you if you go missing. That nightmare has become an internalized reality in so many indigenous communities, where young women are being raised with impressive levels of advocacy for their missing sisters, but are witnessing first hand how much of a struggle that advocacy is. Social media is beginning to catch up to decades of research that has been waiting for a time like now, where the general public may be ready to listen and push for change. The Murder Accountability Project (MAP) has tirelessly collected data on unsolved homicides in the United States to apply pressure on law enforcement in communities with disproportionately high unsolved homicide rates, and put a spotlight on communities that fail to report important information to federal databases. The Indigenous community is heavily reflected in both of those categories.

A broken chain of command and lack of communication is often cited for why so few of these reported cases are ever investigated, as local, state and federal law enforcement agencies struggle to find a balance of working with native land and sovereign tribes through the reporting process. Many violent crimes against indigenous women occur on sovereign native land, however, 96% of the perpetrators are non-indigenous. This causes major confusion as tribal governments are unable to prosecute non-indigenous persons, and most standard law enforcement agencies have no jurisdiction over any crimes that occur on native land. This complicated mess of jurisdiction and authority confuses law enforcement, tribal governments, and victims alike.

Unfortunately, law enforcement has repeatedly made glaring errors that are impossible to ignore; tribal organizations have found that the United States National Crime Information Center recorded 5,712 reports of missing American Indian and Alaska Native women and girls in 2016, but the US Department of Justice’s federal missing persons database shows that only 116 of those 5,712 cases were never logged. Essentially, this information means that only 2% of all cases of missing indigenous women were properly reported. This cannot be ignored; many families, friends and loved ones are left wondering why our government has forgotten and neglected their sisters, mothers, wives and daughters. While the answer may not always be clear, movements like #MMIW are bringing this conversation to the forefront of politics and media. In order to provide justice for these women, we must demand increased preventative and investigative efforts to protect these women when they need it the most.

Truths of Targeting

The vast majority of homicides of indigenous females go unsolved for years, and even the solved cases display how this systemic neglect has been repeatedly exploited. As determined by the FBI, “vulnerability” is a key factor in a killer’s process of victim selection; a category most indigenous women have been forced into by countless factors beyond their control. Prolific serial killers like Robert Pickton (Canada) and Robert Hansen (United States) specifically targeted indigenous women and sex workers during their killing sprees, and doing so allowed them to murder dozens of women completely undetected by law enforcement for decades. More than half of Pickton’s victims were thought to be aboriginal women, though many were never identified, and Hansen’s victims were often young indigenous women who had turned to survival sex work out of financial desperation. While describing research confirming how killers have manipulated vulnerabilities to their benefit, Co-director of MAP and criminologist Michael Arntfield determined that “Serial killers prey on marginalized populations, and indigenous women make up a disproportionate number in the victim pool”.

How to Help

There are many exceptional campaigns, research organizations and nonprofits to get involved that are currently on the forefront of the fight to end violence against indigenous women. If you wish to learn more about the topic, you can explore other Institute of Human Rights articles promoting Indigenous rights here, or click here to find an excellent resource sheet with educational sources and ways to get involved with MMIW. There are countless petitions for reform in both the US and Canada as well; this petition calls for the passing of Savanna’s Act, which will require the Department of Justice to update their missing persons database to better help identify missing and murdered Indigenous women and prevent further discrepancies in reported cases. This petition is a plea to the US Senate, calling for the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) to be re-authorized and receive greater funding as VAWA increases abilities for tribal nations to prosecute non-native offenders as well as providing resources for responses from law enforcement on all levels when cases of violent crimes or missing women are reported. The Coalition to Stop Violence Against Native Women offers ways to donate, volunteer, attend community training, and other incredible opportunities to get involved in the movement. The Sovereign Bodies Institute utilizes donations to collect culturally-informed research on gender and sexual violence against indigenous peoples.

The only way to protect these women is to take drastic steps towards change. We can no longer ignore, deny or neglect the truths of everything both systemic and societal that has consistently failed the indigenous community, and the women within it. Please research, donate, volunteer, and find a way to become an advocate for the missing and murdered. We can have no more stolen sisters.