Now more than ever, people are fleeing their home countries because of war, persecution, or violence, hoping to find a better life in a different country. In fact, we haven’t seen a refugee crisis this large since World War II: there are 70.8 million refugees worldwide, and estimates show that around 37 thousand people are forcibly displaced every day. They risk their lives to escape a situation they feel they won’t survive, but when these refugees finally find a place they feel safer in, they face new challenges, including the education of their children.

Children, in every society and culture, are the future; they will grow up and have an impact on society. The significance of the impact and whether it’s positive or negative is greatly affected by the child’s education. If a child is refused an education, it will be hard for them to positively contribute to society. Additionally, a lack of education can prevent people from knowing their rights and being informed about their health.

For refugee children, education is even more important. In addition to the importance of education in general, education can give a child back their sense of identity and purpose after being stripped away from everything they know. Often, refugee children are taken to a country that is much different from their native country, especially with regards to culture and language. However, receiving an education can lessen the growing pains, especially if teachers are trained to help children from different cultures and speak different languages. Additionally, going to school can help children learn the intricacies of the new culture by being exposed to it for extended periods of time.

While it may seem obvious that education is important for every child, the education gap between refugee and nondisplaced children continues to grow. Worldwide, 91 percent of children attend primary school, but only 63 percent of refugee children attend primary school. While the number drops for secondary school across the board, the decline is much more dramatic for refugee children: only 24 percent of refugee children will attend secondary school. This is alarming because secondary school is typically the minimum level of education needed to attain a desirable job. The vast majority of these children, who are already put at a disadvantage, have even less of a chance of receiving the education they need.

Worldwide, there are many reasons refugee children are not receiving a quality education. First of all, the language in their new country may be different from any language they speak, which could cause them to fall behind in their studies. Second of all, there may be discrimination and bullying, which can make it much harder to focus on and excel at their studies. Additionally, in some areas, there may be limited spots in secondary schools for refugees, limiting the number of refugees that can receive an education. Finally, many refugees are denied the right to attend school, as many governments have policies in place that block their enrollment. These policies can include the requirement of residency documentation, which is nearly impossible to attain, essentially making their enrollment in school impossible.

In the US, there are two laws in place that are meant to protect children’s education: the Flores Settlement and Plyler v. Doe. The Flores Settlement outlines the regulations and restrictions regarding detaining minors, including refugees, at the border. It ensures proper treatment within detainment centers and includes a section specifically regarding education. Children are required to receive an individualized educational plan including basic education and lessons in English. However, in June, there were reports that the Trump administration decided to suspend many services in juvenile detainment camps, including education, because of a lack of resources. This act would’ve gone directly against the Flores Settlement.

Plyler v. Doe protects the rights of undocumented children to get a primary and secondary education, stating that they fall under the Equal Protection clause in the Fourteenth Amendment. Plyler v. Doe shows that in this country, every child has a right to an education. However, this right is not always granted. There are many schools that require birth certificates and ask about immigration statuses as a way to keep undocumented children out of school, even though it is illegal.

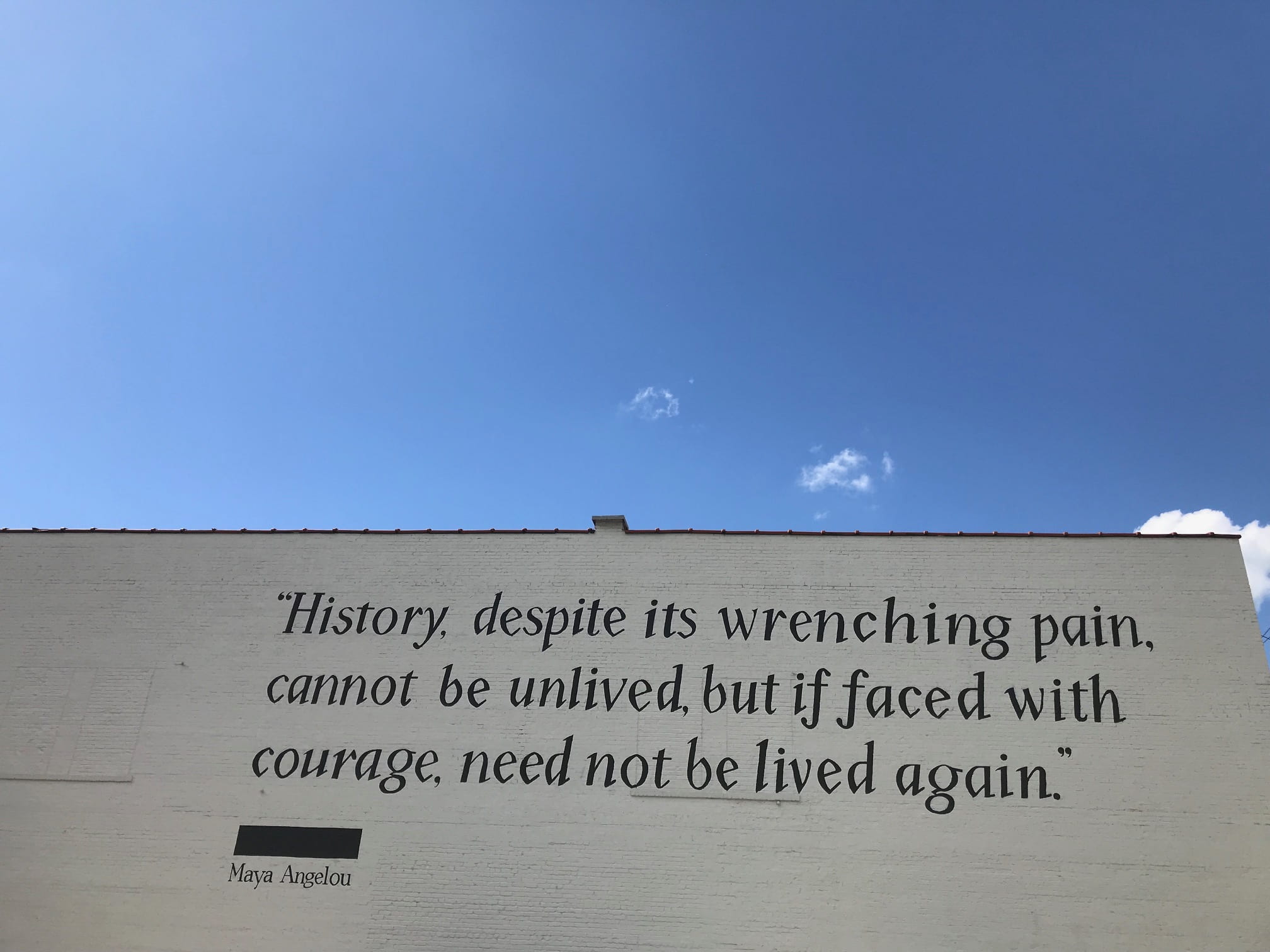

There are many benefits to the communities that accept refugees. Many of those against admitting refugees to Europe, the United States, or wherever they may live, cite the economic strain refugees put on the government as their reason for opposing the intake of refugees in their country. However, they are ignoring the fact that through taxes refugees generally boost the economy more than they strain it. This can only be improved by educating the children as well. The best way for someone to positively impact the economy is to be well educated; in a study done over 40 years comparing 50 countries’ economies and education levels, they found that the higher the average cognitive ability, the faster the gross domestic product (GDP) increased. If a country refuses to educate any of the children that live there—including refugees—it will not only negatively affect the children, but will also negatively affect the entire country. Additionally, schools that allow refugee children will have more diversity, which promotes higher levels of tolerance, not only among them, but also among parents and the community.

It is imperative for the development of the individual and the well-being of the host country that refugee children have the opportunity for an education. However, it is not enough to just give them access to an education. They must have the resources necessary for them to succeed, such as teachers that are willing to work with them through language barriers and accurate credit for courses taken in their native country, among others. They must be given the same opportunities that the other children in the country are given if they are to succeed and we are to close the gap in education between refugee and nondisplaced children. Many countries have already started making an effort to close the educational gap and take down barriers: Turkey has made significant efforts to prepare school-age refugee children for a transition to Turkish schools, and Ecuador has passed laws to give undocumented Venezuelan children easier access to school. There are many benefits to the education of refugee children and ignoring them will have grave consequences for refugees and the communities they are a part of.