Note from the Author: This blog was written to accompany the Social Justice Café Transitional Justice: Here & Now hosted by the Institute for Human Rights at UAB on Wednesday, November 30th at 4:00pm CST. At this event we will discuss a brief history of Transitional Justice in the United States and hold an open discussion about what it could look like in the home city of the Institute, Birmingham Alabama. You can find out more information and join the virtual event here. In this post, we will explore transitional justice in the United States. We will have another post on the international context of transitional justice.

Transitional justice is a field of international justice that “aims to provide recognition to victims, enhance the trust of individuals in State institutions, reinforce respect for human rights and promote the rule of law, as a step towards reconciliation and the prevention of new violations” (OHCHR). Often referred to as TJ, transitional justice is a system of multiple mechanisms and processes that attempt to create stability and ensure justice and remedies for victims of oppression and human rights transgressions. Some of the most commonly used mechanisms of TJ are truth commissions (TCs), reparations, and trials of perpetrators.

In practice, transitional justice has often been restricted to nations following active conflict or repressive authoritarian regimes, otherwise known as transitional time periods. This traditional understanding of transitional justice is beginning to evolve as stable, established democracies like Canada and South Korea implement TJ mechanisms such as truth commissions and reparations to address and amend state-sponsored abuses of certain groups. As it evolves the international gaze has once again turned to the United States and the uncomfortable discussion about the historical and ongoing oppressions. This article intends to establish the historical basis of transitional justice in the United States and recent developments to encourage a conversation about acknowledgement, fact-finding, reparations, and justice in the land of the free.

Section 1: Historical Examples of Transitional Justice in the United States

With an international spotlight on the Black Lives Matter movement in the United States in 2020 came an increase in conversations about reparations to African Americans for the abuses of slavery, segregation, police brutality, prison labor, exclusion from housing and education and other forms of state-sponsored oppression that have proliferated for centuries. The discussion about the harms the American government has caused to Indigenous tribes, Alaskan Natives and people of Hawai’i, and other marginalized groups has been a matter of public discourse for decades. While the word reparations saturated international media, little attention was given to what reparations would truly look like, could look like, and examples of when the United States have provided reparations before.

While the spotlight of this discussion about reparations is often on monetary forms, such as property, cash or pensions, transitional justice recognizes that reparations can and should come in many different guises in order to provide a more holistic and healing process for victims. Reparations are deeply context-specific, and should be tailored to the needs of the victim, nation, and individual circumstance. However, examples of other forms of reparations and TJ include official acknowledgements and apologies, funding of research to uncover facts and educate the public on the truth, providing education and/or healthcare to victims and their families, and preserving historical sights and monuments. Ultimately, they should be determined by and catered to the people involved.

I have included both a brief infographic timeline and a more detailed look at a few examples of government-led transitional justice mechanisms in the United States below. It is important to note that, as many of these instances occurred prior to our modern definitions of transitional justice and reparations, this timeline encompasses cases of compensation which, under similar circumstances today, would likely be considered reparations, but were not explicitly intended as such at the time. The same goes for fact finding commissions that are analogous modern Truth and Reconciliation Commissions, though they lack that title. I have excluded instances of payments or acknowledgements being issued following a lawsuit through our judicial system, as well as instances of TJ being led by non-governmental entities like community organizations, charities or other non-governmental institutions.

- President Lyndon B. Johnson established the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders, otherwise known as the Kerner Commission, in 1967. It was established to serve the purpose of a fact-finding mechanism akin to a Truth Commission today. The goal of the commission was to identify the causes of the violent race riots of 1967. While widely ignored, the Kerner Commission found that the root of the unrest were unequal economic opportunities, racism, and police brutality against minority racial groups in America.

- Following concentrated efforts from interest groups and international attention, the United States federal government committed to two massive examples of explicit transitional justice mechanisms in the 1980s for Japanese Americans that were interned by Executive Order 9066 during World War II. In 1980 President Jimmy Carter signed the Commission on Wartime Relocation and Internment of Civilians (CWRIC) into law, establishing a clear transitional justice mechanism (truth commission) at the national level. The CWRIC published the full report of their findings in February of 1983, and momentum from the commission persisted with the recommendations which were published in June 1983. The recommendations included an official apology, pardons for those convicted of violations of the executive order or during detainment, and the establishment of a federally funded foundation for research and education on the incident.

- Shortly after the results of the CWRIC circulated across the nation, the United States Congress passed the Civil Liberties Act of 1988 which provided all eligible interned individuals with a one time payment of $20,000 in reparations as well as official acknowledgement and apology from the United States. In addition, all individuals who were convicted of disobeying the executive order or violating rules while interned were officially pardoned.

- In response to the massive Black Lives Matter protests in 2020, many subnational level truth commissions and reparations programs were initiated, including those in the State of California, Evanston, Illinois, and Asheville, North Carolina. As the national conversation continues, we may see an increase of examples of transitional justice at work in United States communities.

Section 2: You, us, and the future of transitional justice in the United States

Whether in Europe, Africa, the Asia-Pacific, the Middle East, or the Americas, civil society plays a key role in the transitional justice sphere. Civil society actors are civilian organizations which can be activist groups, media, charities, non-profit organizations, educational groups and schools, or just citizens interacting with policy. Most recent transitional justice measures that have been implemented in the past few years in the United States have been on the subnational level. They are occurring as a result of citizens’ calls for action, constant attention on the need for transitional justice, and the everyday acts of discussing transitional justice.

Birmingham, Alabama is a historic city for human rights, civil rights and civic action. Civil society here, in this city, has influenced national change through the Civil Rights Movement as well as citywide changes like the removal of confederate statues in public parks and the preservation of historic sites from the Civil Rights Movement like the Greyhound Bus Station and 16th Street Baptist Church.

The Institute of Human Rights at UAB fosters an educational environment where you can see civil society at work, and hosts Social Justice Cafes on the second Wednesday of every month during the school year at 4:00pm CST. We will be hosting our last Social Justice Café of the semester, Transitional Justice: Here & Now on Wednesday, November 30th to discuss what transitional justice should look like in American cities like Birmingham. You can find out how to join these open discussions, and become a civil society actor yourself, and attend more free educational events from the Institute of Human Rights here.

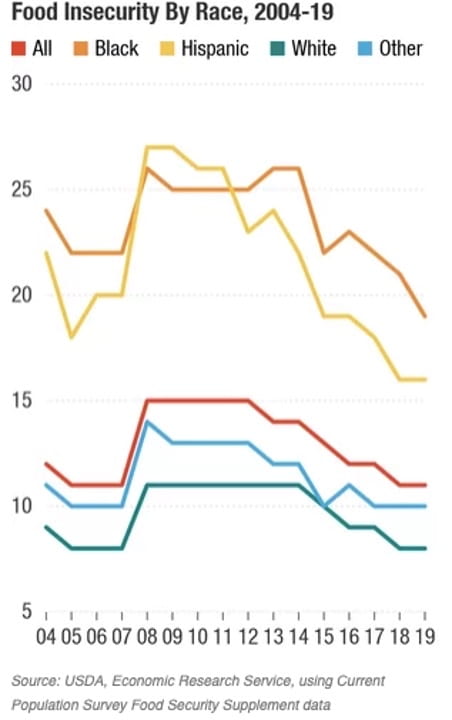

This chart goes on to show the differences between food insecurity rates based on race. Although each demographic has seen a decrease in their food insecurity rate over the last several years, there is still a very large gap between the races, with the biggest difference being between Black and white Americans, who have a difference of roughly 10% between the groups. Even worse, there are countless combined consequences that can hurt already marginalized communities from living in a food apartheid, including an increase in obesity and physical conditions like diabetes due to the lack of access to affordable and healthy food options.

This chart goes on to show the differences between food insecurity rates based on race. Although each demographic has seen a decrease in their food insecurity rate over the last several years, there is still a very large gap between the races, with the biggest difference being between Black and white Americans, who have a difference of roughly 10% between the groups. Even worse, there are countless combined consequences that can hurt already marginalized communities from living in a food apartheid, including an increase in obesity and physical conditions like diabetes due to the lack of access to affordable and healthy food options.