For years the United States (US) has been employing extraterritorial jurisdiction to impose oppressive sanctions on foreigners. Often, these sanctions violate due process rights because they are imposed without providing individuals with adequate notice, a fair hearing, or an opportunity to challenge the designation. The US has the authority to freeze assets, ban travel, and place other restrictions on financial transactions. This significantly impacts an individual’s human rights as the freedom to travel, freedom to work, and freedom to have privacy. Targeting individuals abroad for alleged activities that occurred outside of the US makes it evident that these restrictions are over-complying out of fear, a fear which is rooted in ethnophobia. Many Americans fear immigrants are taking their jobs, and sanctions like this only bolster this. Arbitrarily depriving someone of their property based on where they are from is an inherent violation of human rights. Unilateral coercive measures like the Global Magnitsky Act, Specially Designated Nationals and Blocked Person List, and Office of Foreign Assets Control sanctions have a disproportionately negative effect on international people.

The Global Magnitsky Human Rights Accountability Act authorizes the president to block or revoke the visas of certain “foreign persons” (both individuals and entities) or to impose property sanctions on them. People can be sanctioned (a) if they are responsible for or acted as an agent for someone responsible for “extrajudicial killings, torture, or other gross violations of internationally recognized human rights,” or (b) if they are government officials or senior associates of government officials complicit in “acts of significant corruption.” It was enacted as a deterrent for foreign political corruption but instead was a catalyst for arbitrary detention and arrests without due process. There is a lack of transparency and little to no evidence provided to justify designating individuals under the Act. UN Special Rapporteur Alena Douhan concerned about human rights violations states, “This is a clear violation of due process rights, including the presumption of innocence and fair trial.” The Act allows the US government to impose sanctions on individuals accused of human rights violations and corruption but does not provide them with a fair opportunity to challenge these allegations. Though it serves the purpose of preventing acts of terrorism and maintaining foreign accountability, the language is not concise enough to prevent arbitrary detentions or sanctions.

The SDN list is updated regularly with the names of individuals, entities, and organizations deemed to be involved in a range of criminal activities such as terrorism, narcotics, or arms. Therefore, US nationals are prohibited from engaging in any form of transaction with SDNs. Based on similar provisions under the Patriot Act, the government can block all of an individual’s or entity’s assets in the US. Similar to Magnitsky, there are concerns over transparency and due process violations. There have been inconsistencies in the way that individuals and entities are designated on the list, including cases where some individuals or entities are designated while others engaged in similar activities are not. Since the process behind the designation is not made public, it begs the question what is the real intention behind this decision and are there any underlying motives? Also, the list is public which subjects the individuals on the list to political abuse by targeting people that are seen as political opponents or rivals, rather than based on evidence of wrongdoing. “This is a clear violation of due process rights, including the presumption of innocence and fair trial, “ The Special Rapporteur observed.

OFAC is an office of the U.S. Treasury that administers and enforces economic and trade sanctions based on U.S. foreign policy and national security goals against targeted individuals and entities from foreign countries. OFAC sanctions can have unintended consequences and harm innocent parties, such as businesses or individuals that have no connection to the sanctioned entities or countries. The exterritorial reach the US has over foreign businesses is overt and unnecessary. Similar to the other legislation, there is a significant gap in knowledge between the government and the individuals affected. They do not know what they have done that has caused them to be targeted. The affected parties have no way to challenge these accusations if they are not aware of what they have done wrong, thus hindering the due process. The UN expert mentioned how human rights are infringed upon when US trade sanctions against specific countries penalize foreign companies for doing business.

While these laws are in the interest of national security, we need to reevaluate if their ability to reach their intended goals or if have they just enforced discriminatory, biased legislation. There are concerns about their impact on innocent parties, lack of transparency and due process, extraterritorial reach, and potential for abuse. These are important factors to consider when evaluating the country’s presence in foreign entities. It is important to incorporate human rights protections in the sanctions the government passes because they affect international relations, global human rights, and the preservation of American ideals of democracy and equality.

This blog is part three of the conversation around disability rights, especially as it applies to children within the American school system. If you have not read the first two blogs in this series, I suggest you do so. The first blog focused on the historical view of disability and the American school system’s approach to children with disabilities. The second part mainly focused on the struggles that children with disabilities face within the school system, and how these struggles have been exacerbated due to the recent pandemic. This final part will focus on some of the approaches that have been taken in the past to address people with disabilities, and how they differ from a human rights approach. We will also examine how we can help on various levels, whether we want to focus on our personal abilities or advocate for a larger movement.

Much of what we have established in modern society in terms of children’s rights comes from decades of struggles, from implementing child labor laws to fighting for the right to an education. Similarly, the fight to pass the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) was one sure way to protect individuals with disabilities from discrimination. These rights and more are protected under the United Nations, both in terms of people with disabilities, (Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities, CRPD), and with children’s rights (Convention on the Rights of the Child, CRC). Yet, these developments have only occurred in recent years; the ADA and the CRC were passed in America and the UN respectively, in 1990, and the CRPD was not adopted internationally until 2006.

The ADA, passed in the United States, protected the rights of people with disabilities from being discriminated against in all aspects of society. This was the first major legislation that protected people with disabilities from being denied employment, discriminated against in places of business, or even denied housing. In addition to these protections, the ADA required industries to be inclusive of those with disabilities through (among other things) taking measures such as building ramps and elevators for easy access to upper-level floors and building housing units with people with disabilities in mind. While America had passed the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act or IDEA (originally passed in 1975, and renamed in 1990) by this time, the initial form of this legislation allowed schools to place certain students with disabilities in special programs for no more than 45 days at a time. It was not until its improved form was passed in 2004 that provided the necessary financial and social infrastructure for its successful implementation.

The passage of the CRC, which applies to all individuals under the age of 18, focuses on non-discrimination, the right to life, survival and development, the State’s responsibility to ensure that the child’s best interests are being pursued, including ensuring that the child has adequate parental guidance. Additionally, it focuses on the child’s right to free expression, free thought, freedom to preserve their identity, protection from being abused or neglected, adequate healthcare and education, and includes certain protections the State is required to offer the children, including protection from trafficking, child labor, and torture. Article 23 of this Convention specifically focuses on the rights of children with disabilities, adding that these children have the right to the care, education, and training they need to lead a life of fulfillment and dignity. It also stresses the responsibility of the State to ensure that children with disabilities can live a life of independence and protect them from being socially isolated. Even though the UN passed this Convention in 2004, America is the only nation that has yet to ratify this treaty. This is why certain realities continue to exist, such as what is happening in Illinois.

Finally, we have the CRPD, which entered into force in 2008, only 15 years ago. Influenced by the ADA, the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities was passed to ensure that people with disabilities were fully protected under the law, including from discrimination, with the ability to function as fully pontificating citizens of their societies, with equal opportunities and the right to accessibility in order for them to lead a life with the dignity and respect afforded to their able-bodied counterparts. This convention had massive support and draws from both a human rights focus and an international development focus. What makes this convention unique is the implementation and monitoring abilities embedded within the treaty itself, and it includes non-traditional actors from communities (usually those with disabilities) with specific roles in charge of monitoring the implementation of this treaty. Unfortunately, the United States, while Obama signed the treaty and passed it to the Senate for their approval in 2009, has yet to fully ratify the CRPD treaty as well.

Upon understanding the various nuances of this conversation, we can now explore the three different approaches to defining disability in society. These approaches examine the issues that people with disabilities face and provide models influenced by differing fields of expertise. Many within society view disability as a medical issue and their solutions to the struggles faced by people with disabilities are medically focused. Similarly, others believe that disability is an issue of how society is structured, and their proposals for solving these issues lie within the realms of reshaping society to be more accessible to people with disabilities. Still, another approach built upon the foundations of human rights, focuses on the individual first, and the disability as an extension of their individuality. We will explore these three approaches and their pros and cons.

As mentioned above, some people view disability as a medical issue, and this approach can be categorized as the medical model of disability. This means that they believe that the “problem” of disability belongs to the individual experiencing it and that disability comes from the direct impairment of the person. The focus of this approach is to look for medical “cures” for disability, which can only be provided by medical “experts” based on the specific diagnosis. While it may be true that individuals with disabilities require medical help from time to time, their entire existence does not revolve around this notion of viewing disability as an illness. The focus here is to “fix” the person with disabilities, so they can become “normal” again. This approach also makes use of the “special needs” rhetoric, which can result in the isolation and marginalization of people with disabilities. Media plays a big part in portraying people with disabilities as weak or ashamed of their disability, which can invoke fear or pity for people with disabilities within the larger society.

Another approach that has been proposed is what is known as the Social Model of Disability. In this approach, the “problem” of disability is seen as a result of the physical and social barriers within society that exclude people with disabilities from fully participating in their society. Disability is seen as a political and social issue, and the goal of this model is to be more inclusive and recognize the prevalence of disability within our societies. This means looking closely at the ableist social institutions and infrastructures present within society and attempting to address these manmade challenges posed by people with disabilities. This model recognizes the social stigma around disabilities and recognizes people with disabilities as differently abled rather than viewing them as incapable of living an independent lifestyle. This approach places individuals with disabilities on a spectrum rather than the two categories of disabled and able-bodied. The goal of this approach is to be socially inclusive of all individuals, regardless of their disabilities.

Finally, there is the Human Rights Model of Disability, which builds upon the foundations laid out by the Social Model of Disability and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR). In this approach, the focus is on viewing the individual with a disability as a human first, recognizing that disability is a natural part of humanity that has existed as long as humans have been around. While it shares a lot of similarities with the social model, the human rights approach emphasizes not only the right of every individual to be treated equally before the law but also stresses that a person’s impairment should not be used as an excuse for denying them rights. This is essentially what the CRPD centers around, and the main goal of this approach is to ensure that people with disabilities have equal opportunities and protect their right to fully participate in society, politically, civilly, socially, culturally, and economically.

While the United Nations has a convention that focuses on protecting children’s rights, it is highly debated whether these treaties are being enforced around the world. Child labor is still common in various places around the world, including right here in Alabama. While it can be argued that the US has not ratified the treaty and that is why the UN cannot do anything about this issue, there are other places that have ratified the treaty that still places children in dangerous working conditions and face no real repercussions from these decisions from the UN. In 2019, many tech companies were sued for their use of child labor in other countries to mine the precious minerals they require to produce their devices. Many textile companies within the fashion industry use child labor in nations that have ratified the children’s rights treaty. While the United Nations is trying its best to protect and promote the rights of vulnerable communities, it has not been able to enforce these treaties and regulations, and as a result, atrocities against those vulnerable communities, (including children), continue to occur. How can we as human beings, ensure that all children are protected from harm, not just those able-bodied, living in wealthier nations? This is something that needs to be addressed, and it requires the cooperation of many different nations willing to put their differences aside and work together to find a solution.

As we explored in the human rights model of disability rights, it is the responsibility of society to provide equal access to all its citizens. This includes its citizens who have disabilities, and not doing so would discriminate against those who have disabilities and violate the Americans with Disabilities Act. This means that both on a national and local level, our infrastructure needs to be updated with an inclusive mindset that makes the roads safer and more accessible to all the citizens using them. As a state, Alabama could not only fix the infrastructure, but also pass bills to ensure that people with disabilities receive the care they need, including employment opportunities, medical assistance, food assistance, and any financial help they may require. Furthermore, on a national level, the police (or another department focused on social work) can be better trained to recognize the various disabilities, both visible and invisible, so people with disabilities are not wrongfully imprisoned for “behavioral” issues. This training would help erode the school-to-prison pipeline that has replaced disciplinary standards in American schools and make way for a brighter future for children with disabilities. Finally, the United States can, at the bare minimum, ratify the Convention on the Rights of the Child, signed into existence in 1990 by member states of the United Nation. As we mentioned earlier, the United States is the only nation in the world that has yet to ratify this treaty.

We can all be more mindful of our actions and our ableist mindsets. Next time you walk down the street, pay attention to the roads and sidewalks. Are there any sidewalks for people with disabilities to use safely? Are there curb cuts, and are those curb cuts freely accessible or are they blocked? How accessible are public buildings such as restaurants, storefronts, or even the DMV? Are there enough parking spots allotted to people with disabilities, and are those spots easily accessible, or blocked off by other vehicles? Thinking outside of an ableist mind frame is the first step toward being more inclusive of people with disabilities. It might seem like a powerless and pointless step to take, but the more you start to notice the ableist structures within society, the more you will want to speak up about these issues the next time you have the opportunity. You will also be more mindful of your own ableist actions and how they may have unintended consequences. If you are a parent, you have the ability to question your school’s practices concerning children with disabilities and offer support to the children and their parents. As an individual, you can also contact your representatives to pass legislation that would empower people with disabilities to live independently. As a society, we need to get past the stigmatization of this group and normalize disability being an innate part of being human.

By Caileigh Moose

Source: Yahoo Images

On Wednesday, January 18, 2023, the UAB Institute for Human Rights facilitated a discussion on the issues of juvenile justice and children’s rights. This conversation was led by Dr. Stacy Moak, a member of the UAB Political Science and Public Administration department, who also has a decade of previous experience as a member of the Department of Criminal Justice at the University of Arkansas Little Rock.

The focal point of this discussion concerned the recent incident of gun violence in Newport News, VA, where a local first grader, just six years old, shot his teacher at Richneck Elementary School. After outlining the basic information on the situation, Dr. Moak brought up two broader questions that would become the basis for most of the discussion: how did this happen, and who can be blamed for this incident?

The conversation initially turned towards the issue of how a gun could have ended up in a six-year-old’s hands in the first place. Several participants questioned how a child this young was allowed out of their family home, into their car seat, and stepped into a classroom with a gun in their backpack. In response, Dr. Moak answered that current gun regulation, or the lack thereof, has played a large role. The conversation referenced how the United States has more guns than any other nation in the world, which has been a result of their being ingrained in the American cultural identity. Dr. Moak outlined for the group how the United States lacks major federal safe handling requirements and simple purchase restrictions surrounding firearms, and how those missing safeguards too often mean guns in the hands of minors.

Source: Yahoo Images

Later, when asked by a participant how we need to specifically change or reconsider gun policies in order to prevent these types of events in the future, Dr. Moak referenced a group called Moms Demand Action, a “grassroots movement fighting for public safety measures that can protect people from gun violence.” Circling back to the tragedy at Richneck Elementary, Dr. Moak discussed the existence of several security measures, like backpack checks, at the time of the shooting, and how the district’s current policies failed to prevent the violence. Even when the school was on alert that a gun might have been in the child’s possession, a gun search was conducted, and nothing was found. One participant mentioned how policies and processes designed to stop these tragedies aren’t working effectively, as seen in the Virginia incident, where the safety inspection of a backpack proved ineffective when it failed to catch a hidden weapon. Another discussion contributor argued that the government’s efforts thus far to protect our children haven’t been enough. Referencing the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, a policy centered around the protection of children around the globe, as an example, they pointed out that the U.S. is the only country that hasn’t ratified the convention, even now, 33 years since its introduction.

In first examining the legal culpability of the child, Dr. Moak reasoned that “if we don’t expect rational decisions from them in other aspects of life, we can’t put the weight of their decisions on them when it comes to the justice system.” Although at 6, the defendant in question is not old enough to face detention in Virginia, Dr. Moak reminded the group that numerous other children would fall victim to this system. Depending on the state, children as young as 8 can not only be sent to juvenile prison but be detained in an adult prison or even sentenced as adults themselves. The fact that a child is 11 instead of 6, she argued, shouldn’t make such a drastic difference. In fact, the brain doesn’t finish developing until the mid to late 20s, so trying to judge the character and motive of a human being who is still learning to tie their shoes is questionable. Though, when it comes to minors in general, the question of intent and the capacity to comprehend the severity and the consequences of their actions in a trial setting remains difficult to judge. Unfortunately, Dr. Moak revealed that the current juvenile justice system does little to acknowledge this. Despite her point that “the main right that children are entitled to is our protection,” constitutionally, the only protection they’ve received is an exemption from the death penalty and life without parole. Dr. Moak brought up that Alabama, for example, has only granted parole to a minuscule number of potential parolees, so most life sentences, at least locally, will remain permanent. In fact, the Alabama Parole Review Board has this year, as of February 14th, only granted parole to less than 3% of total parole applicants. Such policy and behavior are by no means unique, and this favoritism of punishment over rehabilitation, especially for children, Dr. Moak worried, will lead to troubling consequences.

Source: Yahoo Images

However, in this case, the only potential avenues of intervention Dr. Moak outlined were Social Services and the child welfare system, as in situations like these, “we’re not treating the six-year-old, we are treating the entire family.” This prompted a discussion of the accountability of parents, with several contributors asking about their potential consequences. One participant asked whether the parents could be obligated to attend some sort of parental or gun safety training as a result of the shooting. On the subject of legal parental responsibility, though, Dr. Moak said there was little to be done, as “juvenile court has no jurisdiction over parents or other adults” as a body designed to strictly deal with youth justice. To mandate any parental action, an adult court would need to be involved.

Finally, Dr. Moak mentioned that a child’s moral compass and rationalization for their actions stem from what they observe around them, whether that be from their parents or their society. One contributor added that American cultural traditions of violence and outright brutality in the face of disagreement seem to have fostered children who aren’t well-versed in conflict resolution. Hollywood was used as an example of this cultural upbringing, producing action movie after action movie that places force as the primary solution behind the dispute, showing them a world where revered heroes act first and talk later. Another participant captured this idea of normalized societal brutality by reminding the group that “we control the storytelling,” and the messages of the stories that will influence the future.

Gun regulation and juvenile justice reforms are notoriously difficult to implement, but some steps can be taken to address some of the more specific issues. For one, we can enact and enforce a moderate national gun regulation policy with a targeted focus on the safe storage and possession of firearms. As a member of society, you can contact your local representatives and elected officials to convey your support for such regulation or donate to causes, like Moms Demand Action, to support their missions. In the realm of youth rights, we can urge our lawmakers to ratify the long overdue UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, while more broadly changing the standard medium of conflict resolution from violence to peace.

Thank you to Dr. Stacy Moak and to everyone who joined or participated in this important and thoughtful discussion! To see more upcoming events like this hosted by the Institute for Human Rights at UAB, please visit our events page here.

Over 60 years ago, the United Kingdom (UK) government secretly planned with the United States (US) government to forcibly remove an entire Indigenous people, the Chagossians, from their homes in the Chagos Archipelago. The Chagos Islands are a group of islands in the Indian Ocean. The UK has a long-standing dispute with Mauritius over the islands’ sovereignty. The UK separated the Chagos Islands from Mauritius in the 1960s, establishing a British Indian Ocean Territory (BIOT) on the islands. The original inhabitants of the islands, the Chagossians, were forcibly removed and relocated to other countries, including Mauritius and Seychelles. The eviction of the Chagossians has been a contentious issue, with many claiming that the UK’s actions were both illegal and unjust. The International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruled in 2019 that the UK’s separation of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius was illegal, and that the UK should cease administration of the islands.

Diego Garcia, the largest of the inhabited Chagos islands, would be turned into a US military base, and the island’s inhabitants would be relocated. This is an ongoing colonial crime because according to article 9 of the Human Rights Act, “ No one shall be subjected to arbitrary arrest, detention or exile.” The UK government forcibly removed the indigenous people from their native, ancestral lands. This removal was carried out without their knowledge or consent, and they were given no say in the matter. This action infringed on their right to self-determination, a fundamental principle of international human rights law.

The reality was the indigenous people had been there for centuries developing their distinct culture, language, and customs. From 1965 to 1973, the UK and US forced the entire Chagossian population from all the inhabited Chagos islands to be displaced from their homeland. Both governments treated the people as if they had no human rights. The islanders were a fishing and coconut plantation community, and their forced removal from the islands cost them their livelihoods. When they were exiled, they were unable to take any of their possessions or belongings with them, and they were not compensated for their loss. This had a significant financial and social impact on their lives.

“My mother cried and said to us, ‘Now we will live a very different life’” quote from Louis Marcel Humbert, born in Chagos 1955. This was in response to leaving four brothers and a sister back on the island. Unable to bring their families with them, many families were broken and left in a similar situation. The strict restrictions imposed by the UK government on access to the islands made it impossible for families to even visit those they have left behind. The governments’ merciless persecution on the grounds of race and ethnicity have resulted in thousands of families being isolated from each other. This is a continuation of the colonization and exploitation of the inhabitators of Chagos. In 1814, the Chagos Islands were ceded to Great Britain as part of the Treaty of Paris, which ended the Napoleonic Wars. The islanders have been subject to forced removal for years.

Despite the International Court of Justice ruling that the UK’s separation of the Chagos Islands from Mauritius was illegal and that the UK should end its administration of the islands as soon as possible, the UK government has retained control of the islands and denied Chagossians the right to return. Full reparations are in order and that starts by granting passage to return back to Chagos. The US and the UK need to provide restitution by immediately lifting the ban on Chagossians permanently returning to the Chagos Islands. This is a human rights violation from over 650 years ago that has yet to be corrected. By acknowledging the islanders were removed unlawfully, both governments can work towards rectifying the situation.

In the last blog, we covered the contextual history of the American Education System, primarily, who was allowed education, who was not, and even the differences in the quality of education that children in America received. We also explored the historical treatment of people with disabilities, both in the larger society, as well as in children with disabilities within the school system. Understanding the past is crucial to analyzing why certain events occur as they do in the future. That is what we set out to do in this continuation of the conversation about disabilities and the American education system. In this second part, we will focus on the realities children with disabilities witness within the education system, including the challenges they face, the school-to-prison pipeline that exists, and how this impacts their development (both mentally and physically). We will then explore how the recent pandemic exacerbated these conditions, and what sort of rights the children possess in this post-pandemic world.

Children with disabilities today face many challenges within the classroom even without taking the pandemic into account. These challenges vary from physical barriers to socio-emotional ones. One thing that needs to be recognized is that not all disabilities are alike, and with various disabilities come various challenges. I don’t want to appear to be generalizing the struggles that children with disabilities face in the school system, because each individual’s experiences vary, even between different places. Some states within the United States may be very inclusive, while others may place the responsibility of accessibility on the people with disabilities themselves. Regardless of which state you live in, my goal here is to spread awareness of the various challenges that children with one or multiple disabilities face as they maneuver through their primary academic journey.

With that being said, one of the most common barriers that children with disabilities face is on the social level. Throughout history, children with disabilities have been separated from the rest of the able-bodied society, and this is also true within the school system. Many schools, when they began to accept children with disabilities into the school system, would educate them separately (in the basement or another room) from the other children. Even today, many children with learning and speech disabilities require additional help from trained professionals, which requires these children to spend extra time on their academics, and less time socializing with their peers. This naturally distances them from able-bodied children their age and can lead children with disabilities to become victims of many instances of bullying and harassment. A crucial element to consider is that while many children their age are dealing with the various emotions that come from development, children with disabilities have to deal with additional fears and insecurities surrounding their disabilities, as they learn to accept and adapt to life with disabilities. This can be challenging in and of itself, without having to deal with the social pressures from peers.

Additionally, while schools receive federal funding to meet the required measures for the children with disabilities within their institutions, this funding is limited, covering less than a quarter of the expenses needed to fulfill the required services for each student. The Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) we covered in the previous blog allows Congress to allocate up to 40% of the average funding per student, but unfortunately, this has never been exercised by Congress, and funding for special education programs continues to be miserly. Schools receive 15% of the funding they are allocated, but they are still required to fulfill all the mandated regulations simply for receiving federal funding. This means that they have to come up with the remaining 85% of the expenditures on their own, in place of the 55% they would be responsible for covering if Congress secured the full 40%. This can place additional strains on these schools that are already struggling for funds.

Furthermore, children with learning disabilities require trained professionals to provide them with additional support throughout their academic journey. Someone who is hearing impaired may require additional resources to combat the auditory issues they face, or someone who is visually impaired may require additional lessons on how to read in Braille. Others with learning disabilities such as dyslexia (which is a disorder in which someone has difficulty reading and processing language), may need additional patience and support to process the information they are learning. Public schools, by law, are required to provide assistance to children with disabilities and those who have been through traumatic experiences. Licensed professionals that focus on educational needs for children with learning disabilities can be hard to find, and this has only worsened due to the pandemic. As many as 44 states experienced this shortage even before the pandemic, and this number continues to grow due to the issues of limited funding discussed earlier. Without the necessary help that students with learning disabilities require, they continue to fall behind their peers academically.

Many of these challenges can be addressed with more funding allotted to the education system as a whole, and professions within the field of special education can be incentivized by the government (by for example, making the training programs free and accessible to those who are interested) to address the shortage of licensed professionals. The education being taught in the schools can be more inclusive of children with disabilities, with opportunities for the children to share their experiences with their peers and help remove the stigma associated with disabilities by normalizing helpful conversations around disabilities. While these challenges can have a great impact on the learning abilities of children with disabilities, there are some challenges that can have drastic impacts on their futures as a whole.

Unfortunately, along with an increase in school shootings within the educational system, another phenomenon that has become all too common is the use of law enforcement to discipline children. More and more stories have been reported regarding children with disabilities and children of color being subjected to drastic disciplinary measures by school systems. When a child “acts out” or showcases any behavior not supported by the schools, the educators have resorted to involving the law instead of following disciplinary protocols within the schools (such as contacting parents, placing students in detention, or for more serious issues, using suspensions). Police are called on these students, and educators watch as young children are punished for their misdeeds by being harassed by the police. In many instances, these incidents have turned deadly, as police officers have used full force on young children, to force them into complying, at times jeopardizing the children’s well-being. Children as young as 7 years of age have been placed in handcuffs and threatened jail time, for childish behavior such as spitting or throwing tantrums. This can be especially dangerous when children with disabilities are involved because they are accused of “misbehaving” when they are simply reacting differently to situations than their able-bodied peers. The police, with little to no training on the different ways to approach people with disabilities, only escalate the already tense situations.

According to a CBS News analysis of data from the Education Department in 2017-2018, children with disabilities are four times more likely to be arrested than their able-bodied counterparts. Another research conducted by Cornell University reports that 55% of Black men with disabilities have been detained before they reach the age of 28. Young African American children with disabilities, therefore, are the most at-risk demographic to face legal repercussions for “behavioral” issues common among most children their age. This phenomenon, known as the school-to-prison pipeline, which disproportionately targets students of color, (and children with disabilities), involves the use of the criminal and justice systems as a tool to discipline children. Unfortunately, these disciplinary attempts remain on the permanent records of the targeted children and can have lifelong implications that determine their future.

An example of this school-to-prison pipeline is clear when looking into some of the instances where law enforcement is used to discipline children. Jacksonville, Illinois is home to a particular school that makes use of its law enforcement officers for behavioral issues. Garrison School, a public school where children with disabilities in that region attend, has been in the news recently for the staggering number of arrests made within a single school year. Although the population of this school is an average of 60-70 children, the police, who are located less than 5 miles from the school, have been called over 100 times for “behavioral” issues, such as throwing tantrums and spraying water. An investigation into this school found that in the school year 2017-2018 alone, more than half of the entire student body was arrested. As the only public school for children with disabilities in that region of Illinois, caregivers are limited in choices of schools for their children. In addition to having disabilities, the children at this particular school have also experienced immense trauma and violence in their past. Arresting these children for their “behaviors” continues to place these children in traumatic situations, further impacting their development.

Using the criminal and justice systems to punish or “discipline” children with disabilities can have lasting impressions on the children’s futures. For one, especially children such as those from Garrison School, who deal with personal trauma and violence from their past, experiences with law enforcement can deteriorate their mental health even further. Even those without previous trauma can have lasting impressions on their academic success, meaning that children who have been disciplined with the use of law enforcement are even more isolated from their peers and can experience breaks in their educational journeys. Studies have shown that children who have their needs met are more likely to outperform those students who do not have their needs met. Linking back to the school-to-prison pipeline, those students who have been arrested and imprisoned as young adults are more likely to continue down this path of criminality. Additionally, students with disabilities that have been imprisoned have to face the added struggles of maneuvering the prison system with disabilities, and these struggles are increased with multiple disabilities, especially with invisible disabilities, in which case, many people may not even believe the existence of these disabilities. Studies have shown how incarceration can worsen issues of mental illness within the prison population, and when translated to the impact imprisonment has on people with disabilities, these conditions are exponentially worse.

In addition to the harm this causes to the development of children with disabilities, the practice of using law enforcement to discipline school children has far-reaching consequences. For one, the children who are constantly “othered,” bullied, or harassed by both students and teachers can internalize their experiences and react to them, increasing their chances of being disciplined again for behavioral issues. In addition to that, being imprisoned, even for a few days, can be a traumatic experience that can shape your worldview, and as a result, your future. For young, developing children, these experiences can be impressionable, and coupled with the isolation that many children with disabilities experience, this can be a devastating combination, resulting in the deterioration of the children’s physical and mental well-being. Furthermore, many of these zero-tolerance policies that end in the arrests of children happen due to the faculty members pressing charges against the children. These charges, though they can be sealed for juvenile offenses, can lead to more charges in these children’s future into their adulthood. A criminal history into your adulthood can result in slim educational and employment options. Research conducted more broadly on this subject has been reported by the Prison Policy, and it showcases how increasingly difficult it is to find decent employment upon exiting the prison system. The report adds that even when formerly incarcerated people do find employment, they are often paid fewer wages than their co-workers.

Applying this research to children with disabilities who are disciplined through the legal system, can be an even bigger challenge for their futures. People with disabilities experience many barriers to obtaining employment even without imprisonment on their records. Studies have shown how incarcerating children does not deter them from engaging in criminal behavior in the future; it might actually have the opposite impact. Finally, children who are incarcerated experience large gaps in their education, and this can impact their ability to successfully enter the job market. This issue is exponentially worse among children with disabilities because they are more likely to be imprisoned for “behavioral issues”, and expands the academic gap felt by so many children with learning disabilities who are already facing many social and learning barriers.

The pandemic was a time of uncertainty, and many of us were scrambling around not knowing what to do. Even as more and more information came out about the virus itself and how to safeguard it, there was a lot of anxiety and misinformation being spread around. Children with disabilities had to navigate not only their personal lives with their unique experiences but also the larger society that was falling apart around them in the face of a virus. Many businesses and schools shut down in the beginning, which meant that children had to adjust to different learning styles, something that may have been easier for some, but widened the academic gap for others. Children with disabilities as a whole had to be mindful of the threat that the virus posed on their lives. This virus was especially deadly to those with pre-existing conditions and for those who were immunocompromised, both of which apply to many children and adults with disabilities. So, constantly having to live with the anxiety of whether or not they might contract the virus would have been stressful enough without the masking and vaccine debates that have politicized this medical crisis. What is worse, COVID-19 vaccines for children were not available for over a year after the pandemic first began, leaving this population vulnerable to infections with no way to protect themselves against them.

Additionally, along with their children, parents, and caregivers of children with disabilities faced new challenges as everyone attempted to adapt to the “new normal”. While the mandated quarantine helped with transportation issues for some, it opened up a whole new set of issues for many. Children with learning disabilities who received additional help from professionals either had to go without it or transition to seeking their help through zoom. For some, accessing help through Zoom and Telehealth was extremely helpful in addressing the medical needs of people, and this had a positive impact on people with disabilities as a whole. However, accessing Zoom and Telehealth was a challenge on its own for many who lived in rural areas or marginalized areas where internet services were very minimal or nonexistent, or simply unaffordable. The pandemic was a time when many people also lost jobs, so children faced additional financial repercussions from the pandemic. These instances further widened the academic gap among children with disabilities.

This blog mainly focused on the struggles that children face within the American school system. Part three of this series will focus on some of the approaches that have been taken historically when addressing disabilities, and some ways in which we can take action, on a personal level, on a local or national level, and even on an international level.

Content Warnings: imprisonment, religious persecution, torture, trafficking, rape, brainwashing

Falun Gong, officially known as Falun Dafa, is a form of qigong, which roughly translates to ‘cultivation.’ Qigong is similar to yoga or tai chi and focuses on the perfection and refinement of mind and body. Falun Gong takes this a step further and incorporates the cultivation of morality and virtue. In 1992, Li Hongzhi introduced the practice to China. As the practice grew in popularity, excitement about the health and wellness benefits associated with the tradition have flourished. Not only this, but the culture of Falun Gong experienced a rediscovery of ancient Chinese philosophies combining elements of Daoism, Buddhism, and Confucianism.

The Chinese government largely celebrated the practice throughout the 1990s, but on April 25th, 1999, the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), led by Jiang Zemin, launched a violent campaign against Falun Gong by issuing a letter expressing their wish to see Falun Gong destroyed. The atheist communist regime, which notoriously rules by the threat of force, was itself threatened by the emphasis on morality and traditional Chinese culture found in practitioners.

Since 1999, an organization called Friends of Falun Gong has reported cases of torture, disappearance, brainwashing, rape, and death of Falun Gong practitioners by the CCP. When a person dies while imprisoned, families are told that their loved one committed suicide or died of a disease, but the bodies are cremated before evidence can be gathered. Notably, a relatively new development alleges that many of these detainees are victims of organ trafficking.

Through propaganda campaigns, the CCP has classified Falun Gong as a xiejiao, which in some contexts has similar implications to the word ‘cult.’ Personally, as someone who actively studies religion and cults, I would not qualify the practice as a cult, as it does not pass any widely accepted tests qualifying organizations as cults.

In my research about Falun Gong, I found very conflicting information about the moral beliefs of practitioners. Officially, they have three significant tenets: Zhen, Shan, and Ren, which translate to truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, respectively. They emphasize ancient Chinese values and, by my evaluation, hold a form of virtue ethics. As far as I can tell, the version being practiced in China is unharmful and beneficial to its practitioners. The relationship between Chinese practitioners of Falun Gong and the Americanized version based in New York is unclear. The following are productions of the official organization of Falun Dafa.

Shen Yun is a dance-based performance/production sponsored and organized by Falun Dafa. They are based in New York City and perform internationally but do not perform in China for fear of persecution. The performance has themes of anti-Marxism, anti-atheism, and a passing instance of homophobia. Jio Tolentino, a writer for the New Yorker, saw the show twice in New York and calls the production uncanny and unsettling. Throughout my research, I have not found any instances of China-based practitioners personally expressing the themes seen in Shen Yun.

![]()

The Epoch Times is a newspaper sponsored by and associated with Falun Dafa. While claiming to be “unbiased,” they post far-right opinion pieces and side with Trump in many of their political articles. To anyone with an ear tuned to the sound of right-wing dog whistles, the Epoch Times website is loud, high-pitched, and painful. Again, I have not found any instances of China-based practitioners expressing the harmful themes found in the Epoch Times. It seems to me that the Americanized version of Falun Gong is a harmful version of what is being practiced and persecuted in China.

Human rights, with respect to a person’s religion, is a complicated subject. Too often, we see people using the excuse of religious freedom to act in a bigoted way toward certain communities. Religion is a personal practice meant, consciously or otherwise, to help a person cope with and understand the trials and tribulations of existing as a human in this world. Sometimes, that religion will come with a set of morals that each practitioner decides to follow. People have a natural right to practice their own religion and to determine their own moral codes without persecution or intervention. But, as with every right, this only extends insofar as it does not impede the rights of others.

The CCP must be held accountable for imprisoning, torturing, and trafficking the organs of Falun Gong practitioners in China. These people are not impeding on the rights of others. They peacefully practice truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance while aligning their body and mind through qigong. In accordance with my working definition of religion, nobody deserves to face religious persecution. Everyone has a right to decide how they will come to terms with and cope with their own existence. It is important that, as humans, we keep certain spaces safe for people to cultivate their spirituality. By taking away every space that may be safe for these people to practice, the CCP is violating their rights.

Even though 1 in 6 people around the world experience disabilities, they are often among the forgotten groups within our society. While people with disabilities today are living under better conditions than their ancestors, there is still a lot of progress needed to be had to ensure that people with disabilities can lead a life of dignity and independence, free from the stigma and failures of society’s ableist mindset. In this two-part blog, we will focus specifically on children with disabilities within the American education system, but before that, it is necessary to frame the historical context surrounding the American education system, and how disability in America has been treated as a whole. As a result, part one of this series will focus on setting the historical context, exploring the American Education System as well as the treatment of people with disabilities throughout American history. The second part of this series will focus on exploring the contemporary issues faced by children with disabilities and their families within the American Education System and learn about a human rights framework for disability rights.

Since the founding of this country is rooted in capitalism, patriarchy, and white supremacy, many groups of people have been historically denied access to education. Traditionally, children from poor backgrounds were expected to help their families on the farm or work in their family businesses to make ends meet. As the industrial revolution took hold, child labor transferred from the farms to the factories, and many industries, such as the textile industry preferred to employ children to exploit their minuscule features. The petite features of the children came into use when they were needed to get into tight spots, or when operating machinery that required smaller extremities. Child labor in America was not outlawed until 1938, meaning that many children from poor families were illiterate and disadvantaged in comparison with children from wealthier families, who could afford to educate their children instead.

In addition to the absence of child labor laws, the patriarchal structure of American society deemed it more important for boys and men to be educated than their female counterparts. While poor families were denied access to education on the whole, even among wealthier families, the education of boys was prioritized over educating women. Women were expected to be homemakers and child-bearers in the private sphere, and the public sphere was reserved for their male counterparts. Many women were denied access to education, were not permitted to participate in politics and were limited to feminine jobs (such as teaching, nursing, and domestic work) when they did participate economically in the larger society. It was not until the 19th century that women were given more flexibility in their pursuit of higher education. Of course, not all women shared the same experiences, and white women were better able to receive education than women from other races, and as expressed earlier, wealthier women had more opportunities to educate themselves than did women living in poverty.

Furthermore, the foundations of white supremacy upon which America was built denied people of color access to education. Education provides the key to empowerment, and the status quo did not want to empower those they deemed to be inferior. Due to the hierarchical nature of this supremacist mindset, people from different groups were “dealt with” in different manners. For immigrants, access to education depended on their country of origin. Some immigrants, such as those from Asian countries, were barred from receiving education in America until the 1880s and were instead used for hard labor, like constructing railroads. European immigrants, on the other hand, were well-received by many in America, (with the exception of the Irish), and were granted many of the rights shared by American citizens at the time. There was however, a difference in treatment between the Old immigrants, (which were members from wealthier backgrounds with skills and education levels from the Southern and Eastern parts of Europe that came to America in the early 1800s), and the New immigrants (who were mostly impoverished, unskilled laborers from Western and Northern Europe who migrated to America in the late 1800s).

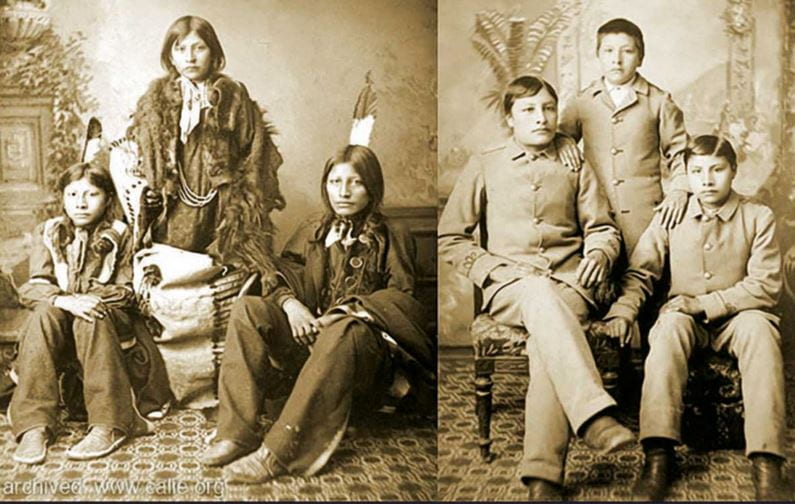

In addition to immigrants, the indigenous population of America also received access to education with a different approach. In an attempt to force them to forget their rich cultural histories and erase the cultural differences between the indigenous population and the larger (White) American society, children from different tribes were kidnapped and forced into boarding schools where they would learn to be assimilated into the American culture. Indigenous children were punished for speaking their language, engaging in their cultural practices, or even wearing cultural clothing (whether it was casually or for cultural practices). This is one of the reasons that today when people appropriate Native American culture (and attire), it can be very insulting, as they were punished for practicing their culture and wearing their traditional clothing.

Furthermore, during the enslavement of African Americans, who were deemed to be on the lowest level on this racial hierarchy, access to literacy was denied to them and outlawed, making it punishable by law for African Americans to be literate. This law was another way in which racist leaders of the time maintained control over the enslaved population. Following this period, there were many racist laws and social barriers to education for African Americans over time, and it was not until the famous passage of the ruling in Brown v. Board of Education that African Americans were given the right to equal education. With all that being said, there is still an ongoing struggle to bring equity, inclusion, and diversity into the American education system.

There can be a whole blog dedicated to the housing market, its impacts on funding for the local schools, and how this influences the level of education the children within those districts experience. As mentioned in previous blogs on similar topics, this funding practice tied to the housing market is, yet another way racism has seeped into American institutions. Transforming the American Education system into a more inclusive one will be a difficult fight ahead, as cries against teachings with an anti-racist approach are molding the current curriculum within the education system today.

This exclusive approach to education also historically denied access to disabled individuals as well. American society has been structured with an ableist mindset, and people with disabilities have been stigmatized and marginalized by the larger society. In the past, many states prevented children with disabilities from attending school, choosing to place them in state institutions instead. Some wealthier families with disabled children could afford to home-school them, but the rest of the children with disabilities within society were not given that opportunity.

Even after education was required for all children, many states refused to provide accommodations for their students with disabilities, and the responsibility of securing access and mobility was placed on the children and their families, rather than the state. Judith Heumann, a well-known disability rights activist, was denied entry to her elementary school during the 1950s because the school district deemed her a “fire hazard” for being mobility impaired and having to use a wheelchair. It was not until the passage of the Education for All Handicapped Children Act (EHC; later known as the Individuals with Disabilities Act or IDEA) in 1975 that educational rights were protected for groups in need, including children with disabilities. While education access was protected under this law, the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) in 1990 was needed to ensure that people with disabilities are protected from discrimination in all aspects of society.

Understanding the historical context behind the American education system is only one part of this conversation. Outlining the lens through which disability is viewed today, and in the past, is necessary to comprehend the treatment of children with disabilities within the American education system. Today, people with disabilities are viewed in four ways. For one, following the traditional views of disability, most people with disabilities are simply ignored by society, both as a population, as well as systemically. You can see this is the case by simply looking at some of the ableist framings of our infrastructure. Needless to say, being an invisible group within society comes with its own challenges.

Another common way society approaches people with disabilities is to view them as the “super-crip” (which is extremely insulting) and look at their achievements as “inspirational.” People who believe this highlight people with disabilities in a supernatural sense, similar to how many African Americans were portrayed as supernatural beings with superhuman strength and abilities. This troupe was not helpful to the African American community then, and it is not helpful to people with disabilities today. Some may argue that this troupe seems to be a positive outlook of the group, but upon closer inspection, it is important to recognize the stress and burden of success this places on people with disabilities to feel accepted by society. It also encourages the mindset that these people who achieve extraordinary things are superhuman and that their achievements are highlighted because there is a general conception that this is abnormal for the group. Additionally, for a person with disabilities, it can be insulting and demeaning to hear the phrase, “if a person with a disability can achieve this, so can you!”

Another tactless way in which people with disabilities are regarded, as inferior to the rest of the population. Many able-bodied individuals either view them as a burden to society or simply objects to be pitied. This can have the impact of treating people with disabilities as second-class citizens and making them feel as if they are lacking in some way or another. Those who show pity toward people with disabilities may have good intentions, but their actions treat people with disabilities as victims of fate, rather than with dignity and humanity.

Finally, some people within society treat people with disabilities as if they have undergone a tragic event (whatever led to their disability), and people require “saving” or “treatment” to be “cured” of their ailments. This too is not the case. People with disabilities adapt to living their lives with their disabilities, and they don’t require anyone to “save” them from their disabilities. This is extremely insulting and rude to even think that, and it has the same connotations as would a “white-savior complex” within the context of race. The underlying belief in both of these situations is that the person doing the “saving” believes that the person that needs to be “saved” cannot do this for themselves and that they require the help of the “savior”.

While it is important to understand the contemporary views of people with disabilities, it is equally relevant to familiarize ourselves with the ways in which people with disabilities have been treated in America in the past. Until the 19th century, people with disabilities were separated from participating with the rest of the larger society. During colonial times in America, people with disabilities were treated in a similar light as the Salem witches, either burned or hanged. Others viewed disability as a sign of God’s disapproval of the colonists, and people with disabilities were treated as though they were possessed. Still, others felt that people with disabilities were a disgrace to their family and their community, and many were shunned from their homes. The larger society lumped criminals, poor people, mentally ill people, and people with disabilities under the same roof, labeling them as outsiders. This practice evolved into the many horror stories that we may be familiar with today regarding asylums and their treatment of their patients. An important note: as it is with other American institutions, racism, and sexism disproportionately impact the lives of people of color and women within these institutions, and this translates into how they are perceived and treated by the larger society as well. This remains true for people with disabilities with identities that are not aligned with the patriarchal, white society.

People with disabilities, along with other vulnerable groups that were stigmatized by society, were pushed into asylums. These were large “hospitals” stocked with medical equipment and personnel in which the goal was to provide care and treatment for the patients that resided within these asylums. The reason I placed hospitals in quotations is that many of these asylums were simply places to house all the people society did not want. These patients were experimented on, abused, neglected, and had almost no rights to defend themselves. Some patients that were from wealthy families were able to be treated at home, but others that came from meager backgrounds were not as fortunate. Many of the staff working within these institutions were unsympathetic towards their patients, feeling burdened by their very existence. Many people (within the institution and outside in the larger society) believed that people with mental illness and people with disabilities were “acting out” on purpose, to make life harder for those “upstanding” citizens of society. Many of the patients were misdiagnosed, and the institutions went from trying to care for the patients to “cure” the patients of their disabilities. The stigmatization of these groups within the asylums meant that their needs and wants were ignored. In addition to that, because it did not require a professional recommendation from a medical practitioner to admit patients into the asylums, many people were wrongly admitted to these institutions (because of personal grudges or disapproval of their behavior) for years without the right to defend and protect themselves.

Of course, it is not wise to lump every institution together and generalize about their treatment of their patients. While some were genuinely trying to take care of their wards and research ways to help “cure” them, others were less sympathetic to the plights of people with disabilities, both visible and invisible. For one, similar to the issues that American prisons face today, asylums were overcrowded, understaffed, and underfunded. This meant that each individual residing within the institutions was not given the personal care they required, and instead, they were all lumped into groups to receive generalized treatments. This was problematic in so many ways, but the most obvious is that disability takes many shapes and forms, and each individual had different needs that had to be met. Approaching a group of people with disabilities with generalized treatments meant that the doctors and nurses never took time to understand the details of each person’s disability, much less how best to approach them. As a matter of fact, because many believed disabilities to be a spiritual problem (a person being possessed by the devil), early “treatments” for mental illnesses and disabilities came in the form of exorcisms. When medical professionals finally were able to understand that this was a bodily illness, not a spiritual one, they then proceeded to conduct various experiments on the patients without having any knowledge of how to treat their patients. This is where the tortures began.

Medical personnel proposed many treatments to “cure” people with disabilities, including inhumane procedures that involved drilling holes into the patient’s skull in an attempt to bleed out the disease in question. While it is easy to judge in retrospect, in the beginning, many of the doctors truly believed that they were “curing” their patients with the various treatments they provided them, even as many recognized the inhumane nature of their treatments.

Other various treatments were administered to the patients, which can be defined as abusive and torturous today. Many women with disabilities were abused sexually, both by other patients and their caregivers. In addition to these incidents, many states (through the support of the law) practiced forced sterilization of disabled individuals in these institutions. The justification for this practice was expressed as cleansing humanity of these various illnesses and disabilities. Inspired by the American practice of eugenics, Nazi Germany expanded upon this practice to include everyone that did not fit their description of the “Aryan” race. To this day, America has not acknowledged this practice, and forced sterilization continues to be legal in the United States because of a Supreme Court ruling in 1927. The case in question, Buck v. Bell maintained that the sterilization of Carrie Buck (a woman who was raped and accused of “feeblemindedness”) was not in violation of the Constitution. This ruling permitted the forced sterilization of thousands of people with disabilities and other traits deemed “unwanted” by the general public. While the Supreme Court has outlawed forced sterilization as a form of punishment, it has never overturned its ruling made in Buck v. Bell. As a result, this practice is technically still supported within the legal framework.

With very little funding, the living conditions within the institutions also proved to be dangerous. The asylum itself was built to be uncomfortable because there was a belief that comfortable living would encourage patients to stay there forever. This meant that there was poor insulation, keeping the buildings cold. Due to the shortage of staff, many patients were restrained or locked up, while others were neglected altogether. These conditions, along with the “treatments” they received, exacerbated the patients’ conditions and were detrimental to their mental and physical health. Finally, as a result of society’s exclusion of this vulnerable population, many people outside of the institutions were not aware of what was taking place within. The patients inside these asylums were all but forgotten, invisible to the rest of society.

In an attempt to expose these terrible conditions to the larger society, journalists and activists spread accounts about the conditions within the asylums. Many were able to do this by investigating these institutions firsthand, and images (and videos) of the ill-treatment of the patients began circulating. As people started learning about the horrific conditions in which their loved ones were being kept in, the asylums faced a lot of backlashes. Amid all the backlash, in 1946, President Truman passed the National Mental Health Act to begin research on neurological issues. It would not be until 1955, however, that things changed drastically for those suffering from mental illnesses. Thorazine, a psychoactive medication that was introduced as a way to treat mental illness, and the population within the institutions peaked around this time. In the 1960s, there was an attempt to take a community-based approach to treat mental health, but it lacked the funding to progress in any substantial way. In 1981, Ronald Reagan takes a drastic step to stop government funding to help with mental health, forcing institutions to close their doors and leaving the patients on the streets.

This dramatic change provided no cushion for the patients to fall on, and much experienced homelessness as a result. With nowhere to go and no help from the government, many people with disabilities lost their lives because of this policy shift. These individuals never received any compensation for their ill-treatment, nor were they given any transitional housing or aid to help restart their lives. Of those that did not end up dead, many people with disabilities were imprisoned for causing “public disturbances.” Unfortunately, this practice continues to exist today, especially impacting people of color, and people living in poverty disproportionately. Of course, the imprisonment of people suffering from physical and mental disabilities exacerbated their conditions, and the lack of care and treatment resulted in many deaths. With nowhere to go, and no rights to protect this vulnerable population, people with disabilities continued to suffer due to systemic failures.

Eventually, following the lead set by the Civil Rights Movement and many other movements such as the Women’s Rights movement, and the sexual revolution that fought for the rights of the LGBTQ+ community, people with disabilities came together to stand against discrimination toward them from the larger society, and fight for their rights to exist and prosper like any other groups. People with disabilities wanted to challenge the practice of institutionalization and employed many of the tactics that were used during the Civil Rights Movement. They staged sit-ins in governmental buildings like the FBI building, challenged the mobility norms of society by blocking busses (that denied accessibility to people with disabilities) from moving, and they protested on the streets, able-bodied allies and people with disabilities alike, fighting for their rights.

People with disabilities were also exhausted with the ableist society they lived in and began to challenge the many barriers within society that kept them from living as independent individuals. They did not need someone to hold the doors for them; they wanted the doors to remain open automatically long enough for them to pass through. They wanted accessible sidewalks on which they could move their wheelchairs, walkers, and other walking devices (if applied) safely, and independently, without having to depend on others to take care of them. People with disabilities and their caregivers began to challenge the largely held view by society that people with disabilities were a burden to society. They argued that societal barriers made them dependent on others and implementing disability-friendly solutions can provide the community with the independence to live their lives freely.

In 1973, with the passage of the Rehabilitation Act, specifically, Section 504, people with disabilities, for the first time, were protected by law from being discriminated against. This act recognized that the many issues faced by people with disabilities, such as unemployment, transportation, and accessibility issues, were not the fault of the person with the disability, but rather, a result of society’s shortcomings in failing to provide accessible services to the group. While this was a major win for this community, this law only applied to those who accepted federal funding, meaning that the private sector, and even many of the public sector, could still discriminate against people with disabilities. Following the passage of this act, many people with disabilities were instrumental in ensuring its enforcement. Many of the sit-ins referred to above happened at this time, as an attempt to keep governmental offices accountable. Protestors would block the entrances into the government buildings, or stay in the buildings past close time, refusing to leave until the necessary changes were agreed to be made to the buildings (such as including ramps to the building or elevators inside the buildings) to meet the Section 504 requirements. This continued until Ronald Reagan issued a task force to stop the regulatory attempts made by supporters of Section 504, and the protections secured by the IDEA, an act that protected the educational rights of children with disabilities. Over the following years, his decision resulted in hundreds of frustrated parents and people with disabilities alike questioning the justification for stopping the regulatory actions of Section 504. This backlash, accompanied by the tireless leaders of the community meeting with White House officials, ended in Reagan reversing his crackdown on Section 504, allowing regulations to continue on businesses that refused to incorporate practices outlined in Section 504.

Additionally, following the passage of the Fair Housing Act in 1968, people with disabilities, along with other protected groups such as race, gender (and sex), and religion, were protected from discrimination in housing. The first passage of the act initially only included race, religion, national origin, and color, as the protected groups. It was not until 1974 when sex (and gender) were added to this list, and not until 1988 when the disability community was added. Still, this act was especially important for people with disabilities because it required home builders to provide reasonable accommodations necessary for the inhabitants to live comfortably and move around the housing unit.

Following these many small victories came the biggest one of them all, the passage of the Americans with Disabilities Act in 1990 (ADA). This law was the first general law protecting people with disabilities from discrimination in all aspects of society, including in housing, employment, healthcare, transportation, and many other social services that impacted the lives of this protected group. The passage of the ADA focused on four main themes: full participation, equal opportunity, independent living, and economic self-sufficiency. Full participation focuses on the ability of people with disabilities to participate in all aspects of their lives, including having access to transportation, entering and exit buildings without issues, being able to vote on inaccessible sites, and enjoying life without social barriers that prevent them from being able to do so. Equal opportunity centers on being able to be employed without facing discrimination due to their disability and being able to take advantage of other such opportunities free of discrimination. Independent living brings attention to the ableist framework that society is structured in and recognizes the need for a more disability-friendly society, with access to handrails, ramps, curb cuts, and other options such as disability-friendly online sites (that for example, speak the menu out for you if you are a person with visual imparities) to raise the living standards for people with disabilities. The basis of this pillar is to empower people with disabilities with tools they can use for themselves in order to live independent life. Finally, the economic self-sufficiency piece mainly concentrates on the economic security of people with disabilities. This includes access and accommodations to receive higher education, better employment opportunities (including training, transportation access, and mobility within the workspace), and other such necessities to promote economic self-sufficiency within the disability community.