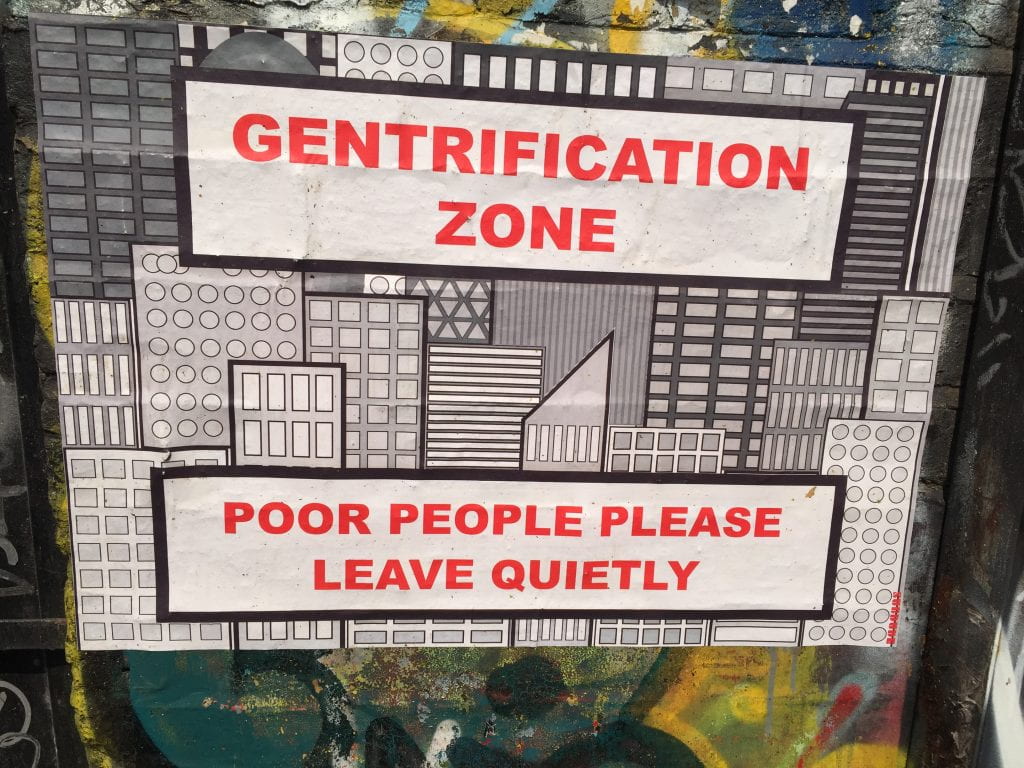

The Merriam-Webster definition of gentrification is – the process of renovating deteriorated urban neighborhoods through the influx of more middle class residents into that area. The process of gentrification is now a global phenomenon and is no longer confined to cities. Communities all over the world are experiencing mass societal development, often accompanied by restored housing, business investments, the formation of new infrastructure and public services such as coffee shops and park. “In most countries, evictions and expropriations are justified on the basis of some form of general interest of society – the so-called “public interest” and this concept has often been abused to justify illegal or badly planned mass expulsions of people. The purpose of business investment in neighborhood revitalization is the production of social capital. Social capital is defined as “the interpersonal relationships, institutions, and other social assets of a society or group that can be used to gain advantage.” Successful social capital and economic opportunities strongly attract and dictate where families choose to reside. In terms of gentrification, social capital is an advertising tool to attract white and more affluent families into revitalized areas.

Various positive aspects of gentrification, such as community development and increased job opportunities, certainly exist. However, negative implications to gentrification, most notably displacement, complicate and in many cases outweigh the benefits. Gentrification-induced displacement (GID) describes how residents may be forced to leave their homes as a result of increased housing costs, housing demolition, evictions, and ownership conversion of rental units. During the progression of GID, increased housing opportunities in gentrifying neighborhoods are more likely to be rented by middle income households, thus gradually decreasing the quantity of low-income renters. Eventually, these neighborhoods become unaffordable to low income residents, and force these lower-income residents to secure living in a less expensive neighborhood; these neighbors likely suffer from issues such as underdevelopment and poverty.

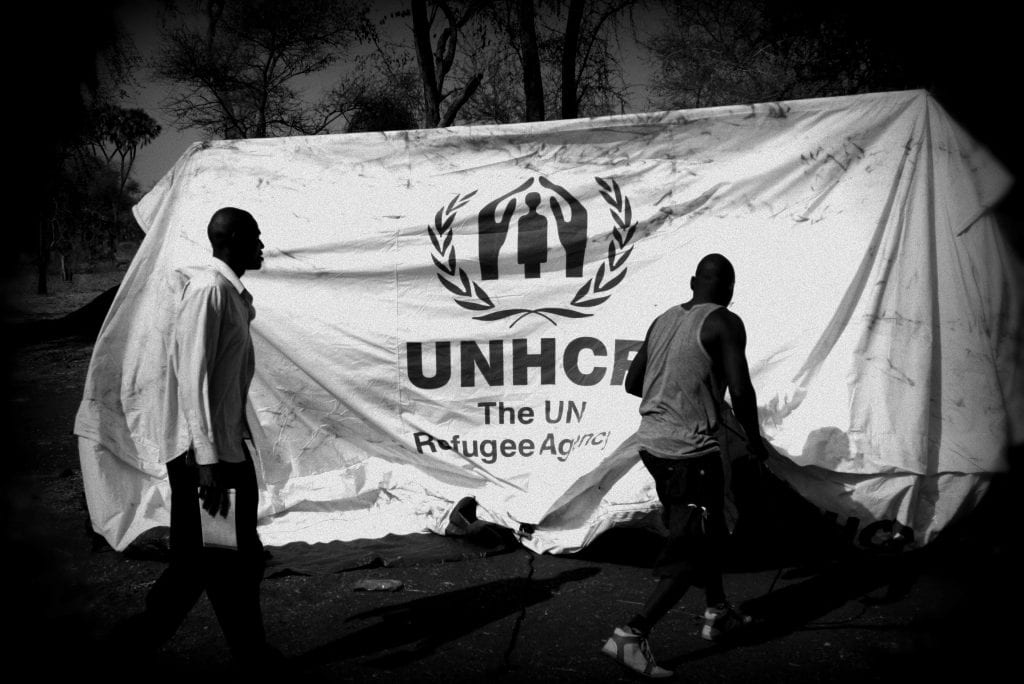

Displacement impedes on the human rights of those forced from their home neighborhoods. The right to adequate housing is addressed in both the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights, specifically stating: “everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, [and] housing…” GID is both a human rights violation and an environmental justice issue. From a global context, the process of gentrification discriminates and targets minorities and low-income populations society. Marginalized populations do not have the political and economic influence to defend their families and communities from displacement. GID compounds these issues of marginalization, thereby multiplying the effects of structural violence on these vulnerable populations. This post will explore the policy prompting GID in two locations: Harlem in New York City, USA and Prabhadevi in Mumbai, India.

Harlem, New York

Harlem has been at the forefront of American black culture. After World War I, factors such as poor economic opportunities and harsh Jim Crow segregations laws in the American South, and the rise of industrial work opportunities in the North promoted the – the relocation of more than 6 million African-Americans from the rural South to the cities of the North, Midwest, and West from 1916 through 1970. In the 1900’s, African-Americans constantly battled the oppression of discriminatory housing policies due to blatant racism. In 1937, under the Housing Act, the US federal government developed the Home Owners Loan Corporation; this and other similar agencies were determined unfit and presented a ‘financial risk’ for investment by insurance companies, loan associations, banks, and other financial services companies. In reality, these agencies were deliberately racialized and designed to benefit more white and affluent populations. As a result, neighborhoods were ranked and color-coded based off race, with the color red representing African American communities. This process, known as redlining, is a method utilized by banks, insurance companies, and other financial companies to deny loans to homeowners who lived in these neighborhoods. As a consequence, neighborhoods deemed unfit for loans were left undeveloped compared to ‘white’ neighborhoods.

After the great migration, racial tension and rising rents in segregated areas in the North, resulted in African-Americans forming their own communities within big cities, thereby fostering the progression of African-American culture. Harlem in New York City, a formerly all-white neighborhood that by the 1920s housed some 200,000 African Americans, is the perfect example of the great migration. The relocation of low income African Americans into Harlem is known as the Harlem Renaissance, and during this period African American writers, musicians, and artists expressed their civil and human rights through their respective artistic media. However, towards the early 1980s, African-American culture and identity in Harlem began to and continues to face the threat of gentrification and subsequent displacement. In 1979, the areas in Harlem lying between 110th and 112th street and Fifth Avenue and Manhattan Avenue, located on the edge of Central Park, were designated for redevelopment by the Harlem Urban Development Corporation. By 1982, 450 housing units displaced by the infrastructural development in that area were relocated into five different units of Section 8 federal housing for low income families. This is just one example of the displacement of low-income minority groups in Harlem. Since the 1900’s, New York City as a whole continues to experience the effects of GID. The effects of gentrification in Harlem are highlighted by the demographic shift happening in the city since the beginning of the 1900’s. In the 1950’s, African-Americans accounted for 98% of Harlem’s population; however in 2015 (just 67 years later), this percentage decreased to 65%. The effect of white “return” to Harlem expedites the process of the displacement of low-income African Americans.

Policies Contributing to GID in Harlem

In Harlem, the disproportionate escalation of housing rental prices, influenced by state housing policies, contributes to displacement. In 1969, New York City established and designated a Rent Stabilization Law (RSL), a form of rent control, to all six or more unit buildings built before 1947. Rent stabilization sets maximum rates for annual rent increases during lease renewal. Every year, the NYC rent guideline board meets to determine the annual rent increase landlords can charge tenants. Currently almost half of the rental apartments in NYC, about 1 million units with 2.6 million people living in them, are stabilized. Still, “rent-stabilized apartments are disappearing at an alarming rate: since 2007, at least 172,000 apartments have been deregulated. To give an example of how quickly affordable housing can vanish, between 2007 and 2014, 25% of the rent-stabilized apartments on the Upper West Side of Manhattan were deregulated.” The intention of this law is to protect tenants from unreasonable rent spikes, however, amendments to the RSL legislation in 2003 created a loophole allowing renters to subvert stabilization. The amendment to RSL legalized preferential rate – “a rent which an owner agrees to charge that is lower than the legal regulated rent that the owner could lawfully collect.” In theory, this amendment is supposed relieve the pressure of rent on tenants, but on the contrary, it provides landlords an opportunity to exploit lower income tenants. Under preferential rent, Owners have the choice to terminate preferential rent and charge the tenant higher legal regulated rent upon renewal of the lease, forcing tenants to either pay more rent or relocate to cheaper housing.

Prabhadevi, Mumbai

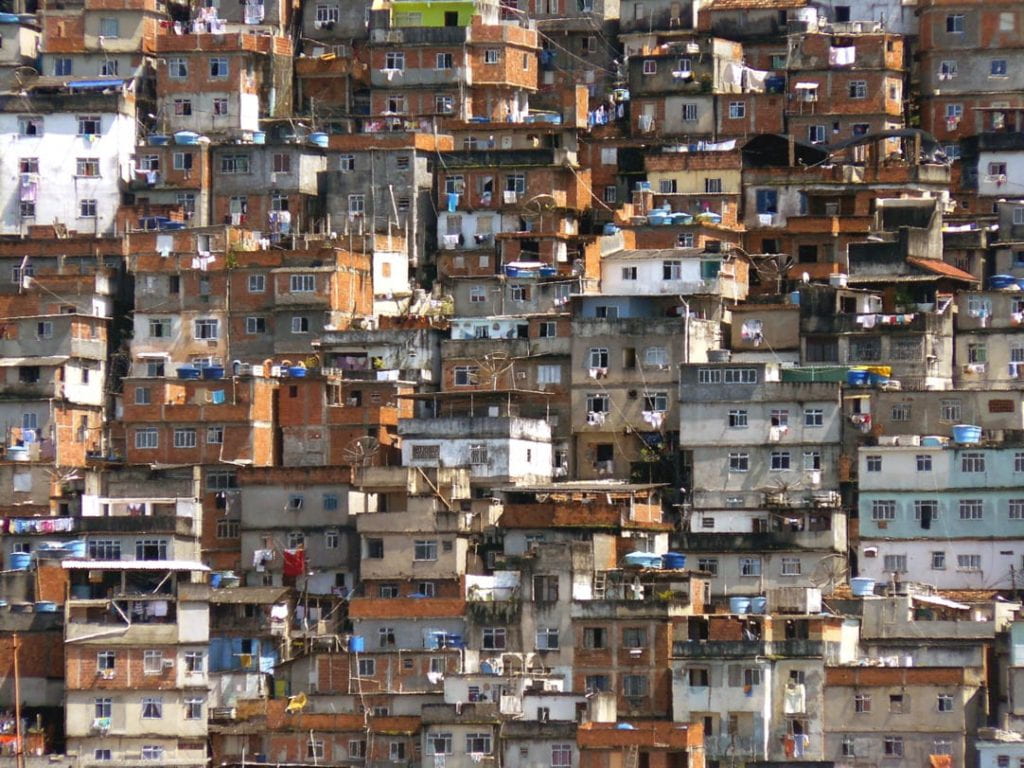

In Prabhadevi, Mumbai, gentrification gained prominence after the decline of textile mills. Post-industrial / neoliberal policies resulted in the sale of mill lands for large amounts of money to private developers. Gradually, huge mill landmass in the main part of the city became a central region for gentrification as land transformed from mills, to malls, and eventually towers. From 2000 to 2001, the area around standard mills was surrounded by 4 slums in which thousands of families resided. After the mills closed, some of the population left the area in search of employment in the suburbs while other families stayed in the area. From 2004 to 2005, the mill lands in Prabhadevi, Mumbai were sold to private corporate builders and remaining agricultural land was redeveloped into high end commercial or residential buildings. Land value and infrastructure continue to develop in this area, and consequently by the end of year 2015, 3 out of 4 slums were converted into Slum rehabilitation (SRA) buildings. The revitalization of these slums into high-rise towers attracted more affluent populations. In 20 years, Prabhadevi underwent a revolution from a rural slum to the down-town and cosmopolitan landmark of the city. The rapid development of the city also contributed to the rent gap between residents. The high-rise towers developing in this area are leased exclusively to the upper-class and elite.

In terms of both Harlem and Prabhadevi, “when rental units become vacant in gentrifying neighborhoods, they are more likely to be leased by middle-income households. Only indirectly, by gradually shrinking the pool of low-rent housing, does the re-urbanization of the middle class appear to harm the interests of the poor.”

Policies Contributing to GID in Mumbai

India’s federal policies play an important role in GID through three mechanisms:

- The process of gentrification in India, which began in 1998, was greatly expedited by federal housing policies. “India’s 1998 housing and habitat policy emphasized the role of the private sector, as the other partner to be encouraged for housing construction and investment in infrastructure facilities. This resulted into rapid growth in private investment in housing with the emergence of real estate developers mainly in metropolitan cities.”

- India’s 2002-2007 Five-Year Plan initiated the ambitious urban renewal program, renamed in 2015, “Atal Mission for Rejuvenation and Urban Transformation” (AMRUT). The AMRUT program administered the rejuvenation of slums, pollution, and urban poverty in over 65 cities.

- India’s federal governments 2012-2017 five-year plan’s main goal is to create a ‘slum free India’ by enshrining public-private partnerships in slum rehousing. “This five-year model gives developers access to valuable slum land in exchange for an obligation to rehouse the displaced slum dwellers in a portion of the multistory flats built on the site- a process known as transfer of development rights (TDR).”

Conclusion

Harlem and Prabhadevi are just two examples of what’s happening every day, all over the globe. As countries and communities continue to develop, land is inevitably going to be utilized and transformed for the sake of public interest. Unfortunately, land is a finite resource, which is the reason why gentrification-induced displacement is a prominent concern and reality for millions of people. As countries and communities continue to progress, we need to start asking ourselves a very important question: is displacement inevitable? If so, what policies are in place to protect displaced people from further marginalization? What policies are currently effective in stopping the GID and how can we implement those policies in different regions around the world? Future research and policies regarding displacement need to address these issues in order to find a feasible and sustainable solution for future displacement. As a global community, we can continue to educate and empower each other to protect our rights, homes, and families.