by Blue Teague

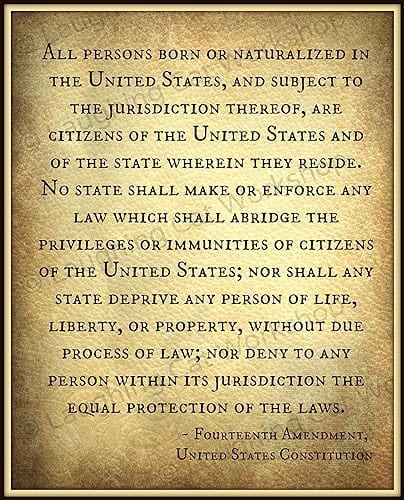

Mental Health, Autonomy, and Psychosocial Disability

In 1887, Elizabeth Seaman—better known as Nellie Bly—published Ten Days in a Mad-House, a collection of articles she had previously written for Joseph Pulitzer’s New York World. Along with cementing her status as a World journalist, her raw, unfiltered reporting offered thousands of readers a rare glimpse into a mysterious frontier: American mental asylums.

A Pennsylvania native, Bly’s anonymous newspaper pieces championing women’s rights soon evolved into a career based on investigative journalism. However, complaints from her subjects resulted in newspaper executives assigning her to less controversial topics. After years of rejection and gender discrimination, Bly made a last-ditch attempt to save her career by approaching Pulitzer directly and weaseling her way into a novel undercover assignment. Critics had called her insane her entire life for her risky stories, and now she had to play the part.

Bly’s articles quickly garnered attention for numerous reasons. For one, the story itself was sensational. After successfully feigning insanity with odd mannerisms and facial expressions, Bly found herself in New York City’s Women’s Lunatic Asylum after a medical professional declared her clinically insane. There she remained for ten days despite immediately dropping the act. During this period, staff allegedly attributed her every move, including normal behavior, to her supposed mental illness. This would have perpetually prevented her release had outside contacts not stepped into vouch for her sanity. By this time, Bly had risen to minor celebrity as New York questioned where this “pretty crazy girl” had even come from.

However, it was Bly’s description of the institution’s conditions that quickly spread through the masses. Her multi-page articles detailed the physical abuse, gross negligence, and psychological harm patients endured.

Sanitation was poor. Disease was rampant. Food and potable water were scarce, and the staff frequently resorted to physical and verbal beatings when dealing with those under their care. Upon her exit, Bly stated that she believed many women there were as sane as herself. If anything, the asylum’s treatment of already vulnerable women caused insanity.

Eventually, a grand jury launched its own investigation into Blackwell Island’s institution, the parent of the Women’s Lunatic Asylum. Despite immense budget increases, the institution shut down a few years later in 1894.

Life in Mental and Physical Shackles

Despite Bly’s work sparking outrage over a century ago, inhumane treatment of those with mental health disorders—or psychosocial disabilities—continues today. According to the World Health Organization, 1 in 8 people live with mental health issues. Without adequate support and resources, these conditions can quickly become disabling. Psychosocial disabilities share strong correlations with higher poverty rates, increased medical discrimination, occupational inequity, and other factors contributing to a generally lower quality of life.

In 2020, Human Rights Watch released 56-page document reporting rights violations of the mentally ill. “Shackling,” a recurring theme, was found in 60 countries across six continents.

Shackling is an involuntary type of hyper-restrictive housing. Although it does not include shackles specifically, restraints such as ropes, chains, and wires are commonplace methods in keeping the victim in extremely close quarters. These areas can be sheds, closets, or even caves. Similar to the asylums in Bly’s era, sanitation is a luxury. The detained person often eats, drinks, and defecates in the same space with little ability to prevent contamination.

The motives and background around shackling is a complex cultural issue. Some offenders tend to be family members who, despite loving the person, lack the resources and/or education to deal with mental health crises. Keeping the person confined can appear to be the safest option when confronted with the possibility of them hurting themselves or others.

Additionally, social stigma can create even more danger for the family as a whole as well as the mentally ill individual. Instead of risking exile or ostracization from the community, families may seek alternative healing methods at home, such as herbal remedies, that lack significant medical backing. This, in turn, can intensify psychosocial disability, leaving the family overwhelmed and confused with few options.

Abuse at the Systemic Level

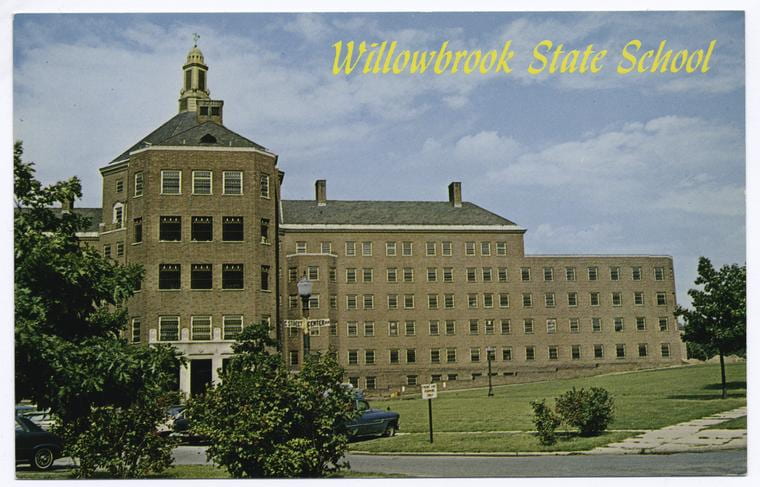

However, abuse does not just occur at the familial level. Mistreatment and abuse flourish in large institutions. The institutions go by many names: asylums, mental hospitals, psychiatric healing centers, etc. These are establishments, often state-funded, purposefully keeping those with psychosocial disabilities away from the general population. Although the institutions usually operate under the pretext of healing and protecting the mentally ill, many criticize the asylum system for blatant human rights offenses.

The abuse is systemic when many perpetrators organize and hide the mistreatment of victims. One such man, “Paul,” shared his experience with reporter Kriti Sharma from HRW’s Disability Rights Division. Paul had lived for five years in a religious healing center in Kenya. He said, “It makes me sad…It’s not how a human being is supposed to be. A human being should be free.”

Paul and his companions walked in chains—literal shackles—and were not allowed clothing. His restroom was a bucket.

In the USA, a wave of deinstitutionalization in the 1970s shuttered many mental asylums, and psychiatric facilities still operating do so with varying levels of success. New York City’s mayor Eric Adams recently announced an expansion of a law allowing months-long involuntary commitment to hospitals for those who, due to mental illness, failed to acquire “basic needs” such as shelter and food. Hospitalization would, in theory, provide the psychosocially disabled with the time and education to recover and start anew.

Opponents quickly pointed out flaws in this process.

As with shackling, involuntary hospitalization represents a loss of autonomy. In a 2022 article in The Guardian, Ruth Sangree reflects on the USA’s changing legislation by connecting it to her own experiences. She describes the monotonous isolation, undercurrent of fear, confusion resulting by the sudden loss of control over her own life. As a nineteen-year-old with no idea of when she would be “set free,” Sangree focused on appearing normal in fear of indefinite hospitalization, regardless of the effectiveness of treatments.

There stands the argument of many critics of institutions: the system is ineffective at best and traumatic at worst. Still, rebuttals exist. In one Times piece, retired employees from a California asylum vouch for the happiness of their patients, stating they “blossomed” when provided with regimen and shelter. This view forms the defense for New York’s law revision, which frames involuntary hospitalization as a compassionate action for the patient’s own well-being.

Objectively, both sides claim to want the same thing: a better quality of life for those with psychosocial disabilities. It has always been the how that stirs debate.

The Future of Mental Health Care

One factor in the corruption of institutional systems lies in language. Terms like “healing center” and “asylum” have historically protected potential perpetrators from legal action. Nellie Bly’s work helped lift the veil around mental health and disability, peeling away the euphemisms to reveal the abuse of a vulnerable population.

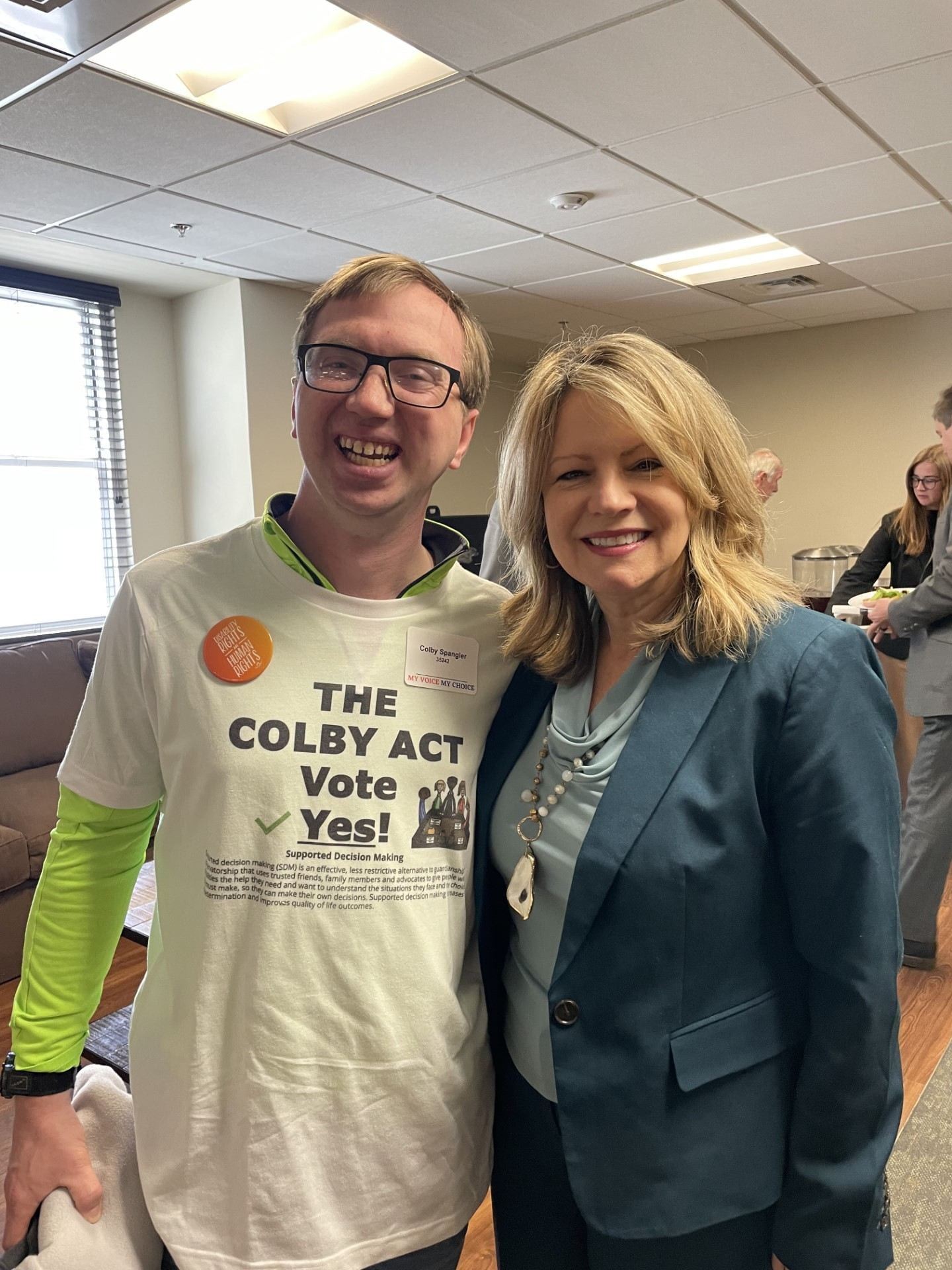

Today, watch groups exist for this reason. Organizations such as the Alabama Disability Advocacy Program (ADAP) examine the care of people with disabilities in facilities like hospitals, nursing homes, and schools, where caregivers can easily take advantage of those under their care. If rights violations are found, they can work with the facility to improve conditions or take legal action. These organizations exist on a state and national level in the USA.

Individuals can make a difference by simply learning about mental health and advocating for equal treatment of those with mental health conditions. #BreakTheChains is a movement led by Human Rights Watch with goals of educating communities to prevent the chaining of men, women, and children with psychosocial disabilities.

Additionally, awareness is key—October is recognized as mental health awareness month, and invisible disabilities week is in late October. Psychosocial disability month specifically takes place in July.