April is Genocide Awareness and Prevention Month. The word genocide brings to mind the well-known horrors of the Holocaust, Rwanda, and the former Yugoslavia; yet, numerous atrocities that have gone unnoticed and unmentioned. I will focus on dehumanization, extermination, and denial for this blog to bring awareness by shedding light on and bearing witness to the history of the Bengali people. For clarity, dehumanization is defined as when one group denies the humanity of another group, extermination is the action of mass killing itself, and denial refers to the perpetrator’s effort to disprove that the genocide ever occurred.

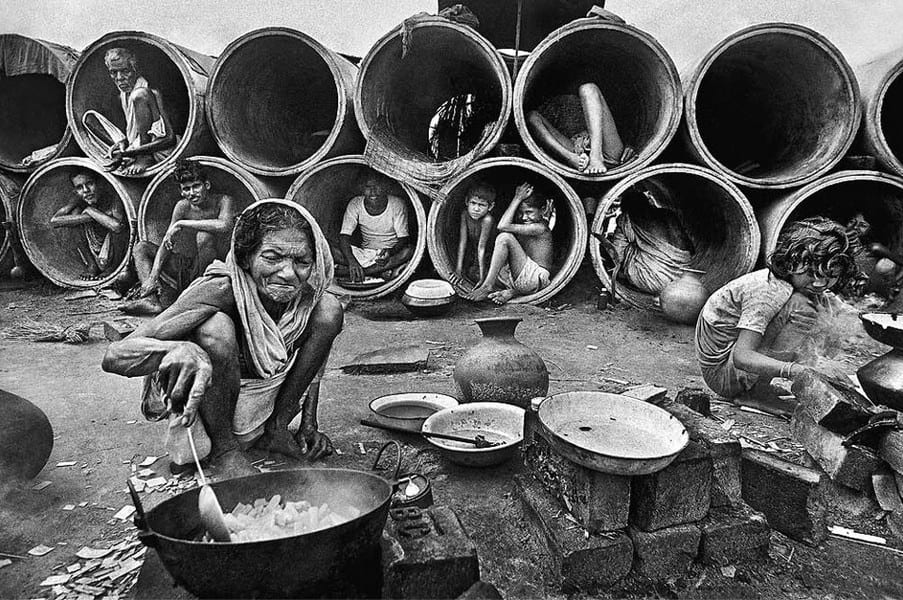

During the 1970s, a genocide took place in present-day Bangladesh. Rough estimates approximate a death toll numbers of nearly 3 million. The systematic annihilation of the Bengali people by the Pakistani army during the Bangladesh Liberation War, targeted Hindu men, academics, and professionals, spared the women from murder, but subjected nearly 400,000 to rape and sexual enslavement.

Bangladesh, as a nation, did not exist prior to 1971 because it was part of an area called “East Pakistan”. The pursuit of independence for Pakistan came following India’s independence from Britain. At the time, religion and culture separated the East and West sections: West Pakistan was populated by mostly Muslim Punjabis, while East Pakistan was more diverse with a considerable population of Hindu Bengalis (Pai 2008). West Pakistan looked down upon their eastern neighbors, calling the area “a low-lying land of low-lying people” who “polluted” the area with non-Muslim values (Jones 2010). This is a clear demonstration of dehumanization which Stanton says “overcomes the normal human revulsion against murder” by equating the victimized groups to vermin and filth. Lacking empathy for their disregarded neighbors, the people of West Pakistan abused their eastward neighbors economically and through lack of aid. West Pakistani elites, living and working in the political center of the country, siphoned most of the country’s revenue, initially generated by East Pakistan (Jaques 1999). Additionally, West Pakistan neglected to send adequate aid following the Bhola Cyclone that ravaged East Pakistan, and left close to 500,000 dead in 1970 (Pai 2008). The amalgamation of denied human rights contributed to the commencement of the Bengali independence movement. In response to the Bengali’s call to secede, West Pakistan developed Operation Searchlight.

Operation Searchlight is seen by many as the first step in the Bengali genocide (Pai 2008). Per the Bangladesh Genocide Archives, the operation, initiated on March 25, 1971, resulted in the death of between 5,000 and 100,000 Bengalis in a single night. Forces of the Pakistani Army targeted academics and Hindus, specifically murdering many Hindu university students and professors. The goal of the operation was to crush the Bengali nationalist movement through fear; however, the opposite occurred. Enraged at the actions of the Pakistan Army, Bangladesh declared its independence the following day (Whyte and Lin Yong 2010). Over several months, the Pakistani Army conducted mass killings of young, able-bodied Hindu men. According to R.J. Rummel, “the Pakistan army [sought] out those especially likely to join the resistance — young boys. Sweeps were conducted of young men who were never seen again. Bodies of youths would be found in fields, floating down rivers, or near army camps” (Carpenter 2016).

Men became primary targets (almost 80 percent male, as reported by the Bangladesh Genocide Archives). The abduction and subsequent rape of women by soldiers took place in camps for months. Many more were subject to “hit and run” rapes. Hit and run rape explains the brutality of forcing male family member–before their own death–view the rape of their female family member by soldiers (Pai 2008). The use of rape, as a weapon of war by Pakistani forces, violated 200,000-400,000 Bengali women during March and December 1971. The high number represents the complicity of religious leaders who openly supported the rape of Bengali women, referring to victims as “war booty” (D’Costa 2011).

Archer Blood, American ambassador to India, communicated the horrors to US officials. Unfortunately, the United States refused to respond because of Pakistan’s status as a Cold War ally. President Nixon, taking on a flippant and discriminatory attitude, regarded the genocide as a trivial matter, assuming a disinterested American public due to the race and religion of the victims. His belief that no one would care because the atrocities were happening to people of the Muslim faith (Mishra 2013), created an uninformed and disconnected America concerning the Bengali genocide of 1971.

“Our government has failed to denounce the suppression of democracy. Our government has failed to denounce atrocities… Our government has evidenced what many will consider moral bankruptcy.” – Archer Blood, American ambassador to India

Pai (2008) suggests the Pakistani Army strategized the genocide into three phases over the course of 1971:

- Operation Searchlight was the first phase as discussed earlier, which took place from late March to early May. It began as a massive murder campaign during the night of March 25, 1971. The indiscriminate use of heavy artillery in urban areas, particularly in Dhaka, killed many, including Hindu students at Dhaka University.

- Search and Destroy was the second where Pakistani forces methodically slaughtered villages from May to October. This is the longest phase because this is when Bengali forces mobilized and began to fight back; rebel Bengali forces “used superior knowledge of the local terrain to deny the army a chance to dominate the countryside”. This was also the phase in which the Pakistan army targeted women to rape, abduct, and enslave.

- “Scorched Earth” was the third phase beginning in early December, and targeted and killed 1,000 intellectuals and professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and engineers in Dhaka. The Pakistani Army surrendered to Indian forces days later, ending the genocide on December 16, 1971. Though Bangladesh established its initial independence directly following Operation Searchlight, the people of Bangladesh established themselves and their nation as a peaceful country, and began the reconciliation process.

The American government has never acknowledged the actions of the Pakistan Army as a genocide. Henry Kissinger characterized it as unwise and immoral, but never termed it to be genocidal. The horrible acts that occurred to the Bengali people was clearly a genocide under the terms of the UN Convention on the Convention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide of 1948 (CPPCG). The CPPCG defines genocide as “any of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.”

Pai (2008) asserts, “That the genocide took place in a context of civil war, communal riots (which include instances where Bengalis did the killing) and counter-genocide, should neither mitigate nor detract us from the fundamental conclusion that casts the Pakistan army as guilty of perpetrating genocide.” To this day, Pakistan has continued to explicitly deny the occurrence of a genocide. Despite this, the atrocities that mark the journey to Bangladesh’s independence have not swayed the Bengali people; their rich culture and flourishing country provide clear evidence. Today, Bangladesh is a prosperous country, ranking 46th of 211 countries in terms of GDP. They are one of the largest contributors to UN Peacekeeping forces, and the Global Peace Index ranks them as the third most peaceful country in South Asia (behind Bhutan and Nepal).

Works Cited

Boissoneault, Lorraine. “The Genocide the U.S. Can’t Remember, But Bangladesh Can’t Forget.”Smithsonian.com. Smithsonian Institution, 16 Dec. 2016. Web. 11 Apr. 2017.

Carpenter, R. Charli. ‘Innocent Women and Children’: Gender, Norms and the Protection of Civilians. Routledge, 2016. Print.

D’Costa, Bina. Nationbuilding, Gender and War Crimes in South Asia. London: Routledge, 2011. Print.

Jones, Adam (2010). Genocide: A Comprehensive Introduction. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-48618-7.

Pai, Nitan. The 1971 East Pakistan Genocide – A Realist Perspective. International Crimes Strategy Forum, 2008. Print.

Weber, Jacques. “THE WAR OF BANGLADESH: View of France.” World Wars and Contemporary Conflicts, No 195.1999, pp. 69-96.

Whyte, Mariam, and Jui Lin Yong. Bangladesh. New York: Marshall Cavendish Benchmark, 2010. Print.