by GABRIEL WRIGHT

** I read and utilized Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. book, Why We Can’t Wait, as the basis of this blog. The page numbers (xx) refer to the specific edition in the hyperlink.

One of my grandfathers was an old Cajun from south Louisiana who cooked gumbo when I was a kid. His gumbo was always different because it was always full of whatever meat he had available at the time. Once, it consisted of duck with sausage and crab, while another time, it contained shrimp, chicken, and sausage. No matter what the ingredients, the gumbo was always good.

Growing up my parents were pastors and missionaries. We moved…a lot! I learned at a young age that to have friends I would have to accept people with all their differences. I attended eight different schools, in two states and three countries from kindergarten through graduation. I was the outsider often. Rejection became my norm. In 7th grade, we lived in Auburn, Alabama. I was not cool enough to sit with the white kids at the lunch table so I became the palest face in at the end of the other table. In high school, my friends and I called ourselves, “The Losers”, a ragtag bunch of racially diverse rejected kids that included guys from the Philippines and Nepal.

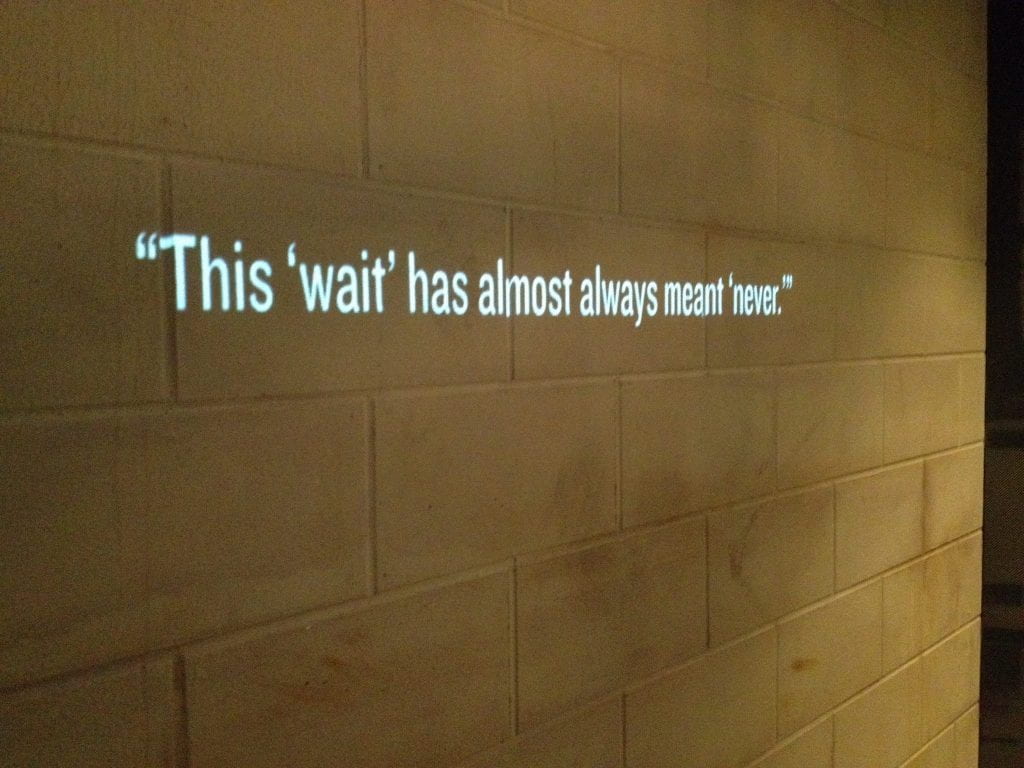

Accepting differences is an essential step to developing unity. Every person, regardless of skin color or background, can wage war against injustice without having a national stage. The fight to right injustice is overwhelming; the enormity of the task can produce fear that paralyzes, causing many to do nothing. Therefore, I prefer to think that there are small battles to be won every day which come through the removal of fear and the creation of change. Unity exists on the other side of the willingness to change. Here are some strategies and keys to remember that can help us bring about change to achieve unity.

First, discrimination, including racism has a spiritual element. I used to think that racism was a preference or color issue. Now I realize racism is a heart condition. If I were to offer any solution to our current state of unrest and violence, it would begin with prayer. I realize it does not sound like a solution because there is no visible action; however, not everything is visible. The Apostle Paul, in his letter to the Ephesians, says that we do not fight against flesh and blood enemies, but against spiritual unseen forces. Dr. King understood this principle well.

The nonviolent direct action of the Birmingham Civil Rights movement was brilliant. King understood that combating people like Bull Connor with physical violence would result in colossal failure. To be a part of the movement, each participant had to commit–not only to the cause of freedom and the values of non-violent direct action–but to prayer (68). People say, “we need to pray for our nation” to no longer remain divided by racism. Often, prayer for the nation looks like an outward one, directed at the heart of someone else, rather than an inward one, directed at your own heart. King David, prayed in Psalm 139, “Search me…know me…test me, and see if there is anything in me that offends you…” The first step in overcoming division in the nation is identifying division in the heart. Ask God to reveal if there is division in your heart. The Bible calls for repentance. It sounds like a fancy church term but it simply means to turn away from what is wrong and move toward what is right.

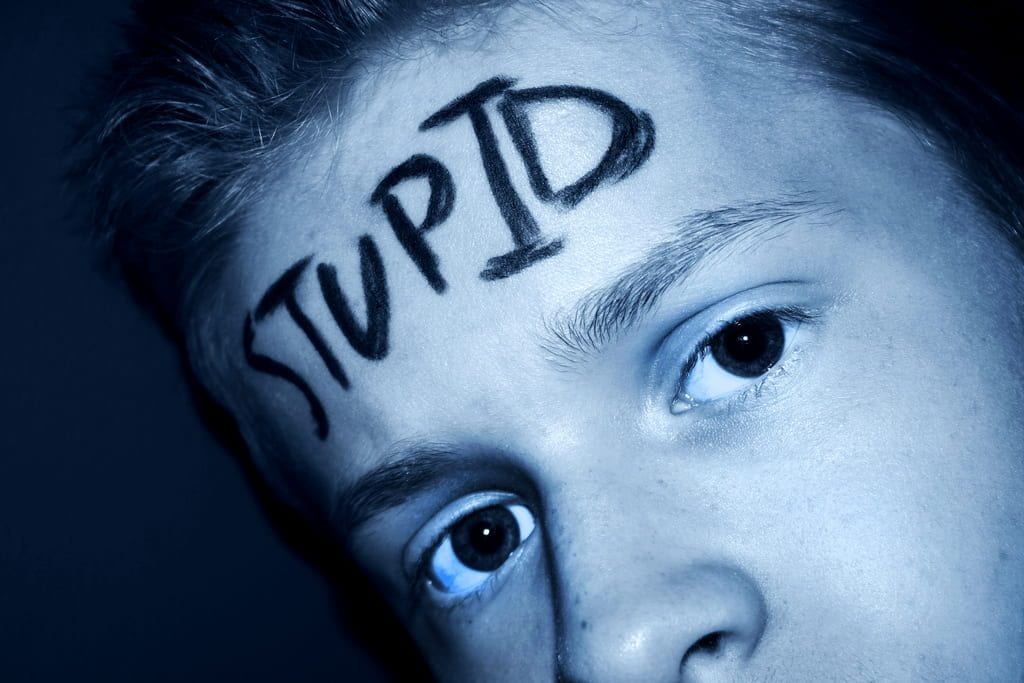

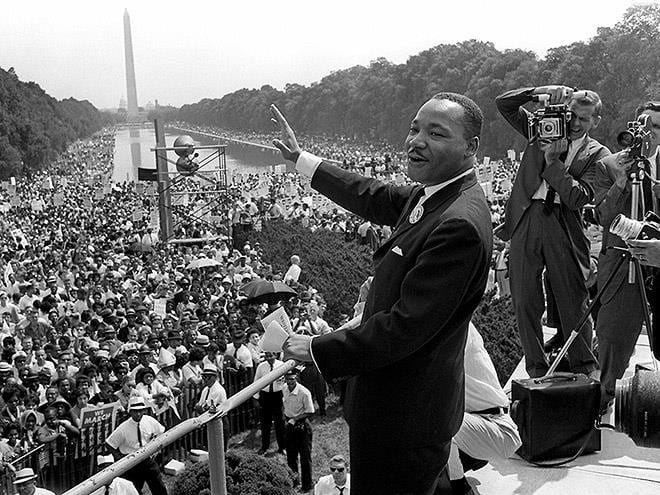

Second, stereotypes distort and divide. Stereotypes are widely held but fixed and oversimplified ideas or perceptions of people. Dr. King asserted that the March on Washington dealt a heavy blow to the perpetuated stereotype about blacks. “The stereotype of the Negro suffered a heavy blow. This was evident in some of the comment, which reflected surprise at the dignity, the organization and even the wearing apparel and friendly spirit of the participants. If the press and expected something akin to a minstrel show, or a brawl, or a comic display of odd clothes and bad manners, they were disappointed” (153). The decision to shatter stereotypes is not about being or becoming a false version of yourself; it is more a decision to recognize that we are not bound to act like the stereotypes placed upon us. As a pastor, one of the stereotypes I battle against is that all I want is your money. My plan was to be generous toward our people and to never ask for money from our visitors so when I planted my church, I decided that I would not give anyone a reason to believe that stereotype. Stereotyping is the byproduct of a spirit of division. Abraham Lincoln famously quoted Jesus Christ in saying, “A house divided against itself cannot stand”. The best way to bring down a nation, organization, or family is through division.

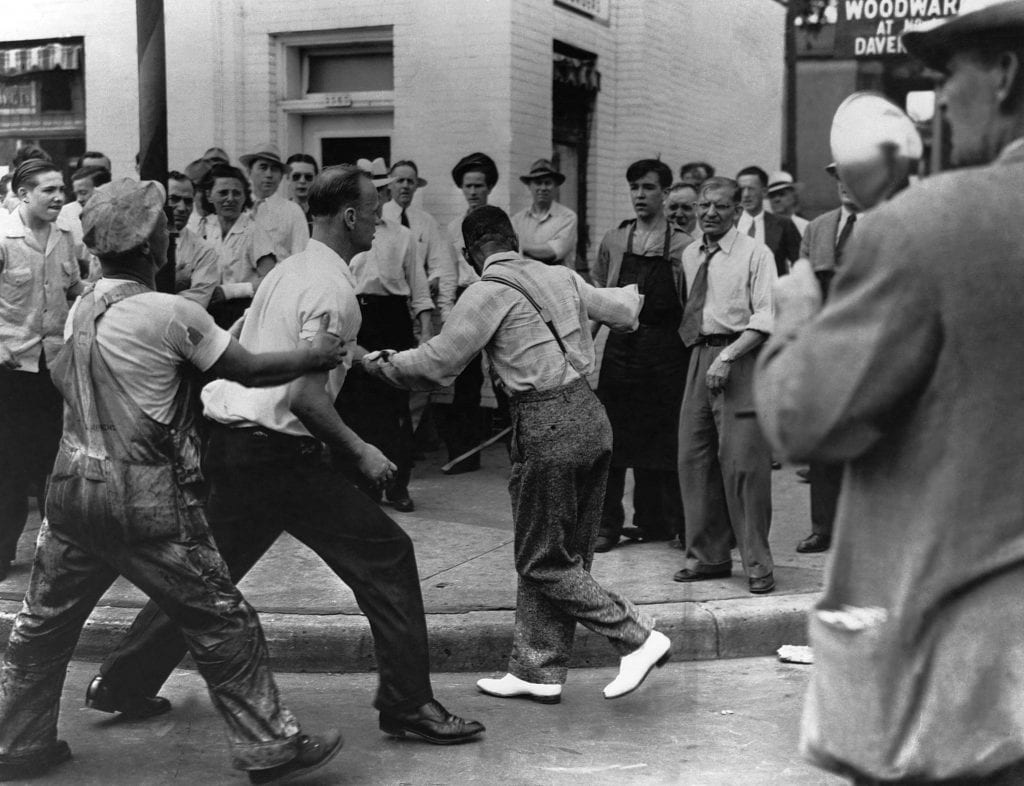

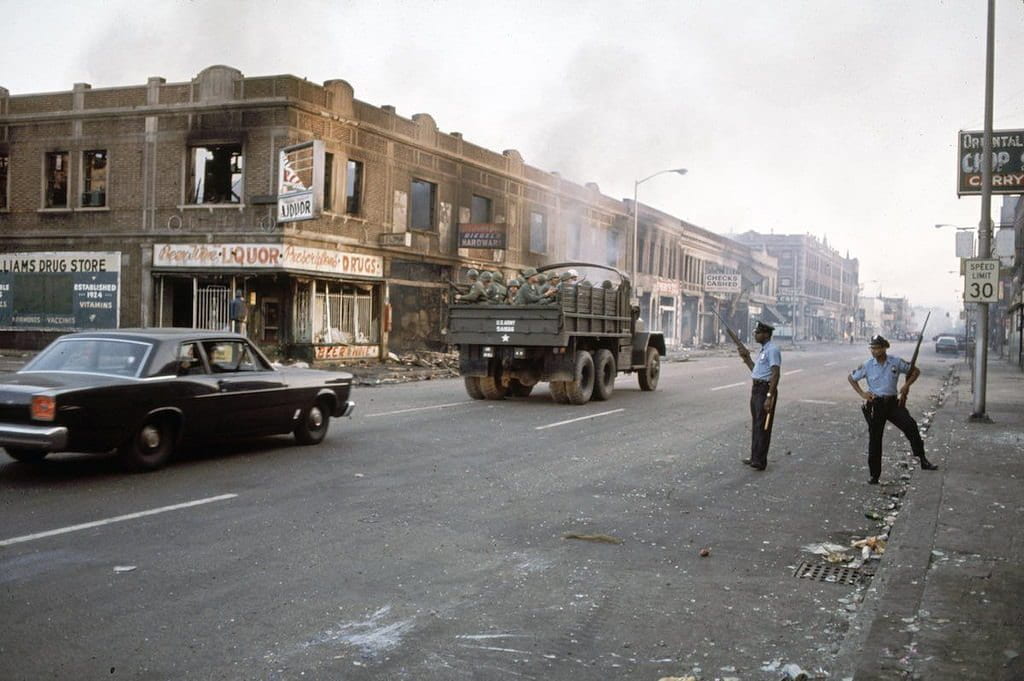

I can see that spirit operating against Dr. King and the movement in 1963. The bombings began after the movement achieved great victories and won many converts to the side of justice. “Whoever planted the bombs had wanted the Negroes to riot. They wanted the pact upset” (128). The stereotype of blacks had been unsubstantiated rhetoric, used to undervalue and suppress. It was with this in mind–the spirit of division–that pushed men to plant bombs, knowing it would give rise to violence and division, not only between black and white, but within the African American community itself. Thankfully, Dr. King and Rev. Shuttlesworth had taught the African American community about the spiritual as well as the physical. “I shall never forget the phone call my brother placed to me in Atlanta that violent Saturday night. His home had just been destroyed. Several people had been injured at the motel. I listened as he described the erupting tumult and catastrophe in the streets of the city. Then, in the background as he talked, I heard a swelling burst of beautiful song. Feet planted in the rubble of debris, threatened by criminal violence and hatred, followers of the movement were singing ‘We Shall Overcome’” (128). The movement realized that they were not fighting flesh and blood, which would be a losing battle; but in the spiritual, with prayer and song.

Never let a stereotype define you. Look for opportunities to deal stereotypes a “heavy blow”.

Third, understand that meekness means strength under control. Many people were against Dr. King’s stance on non-violent direct action. For them, action without retaliation was weakness, not strength, specifically when Connor turned water hoses on protesters. Jesus once said, “The meek will inherit the earth”. When we are meek, it doesn’t mean that we are lowering ourselves, but we are controlling ourselves and taking the ammunition away from our enemies.

Next, we cannot expect to overcome injustice and racism without setting up the next generation. I’ll never forget my friend Cedric. He lived in a very violent, crime ridden government housing project. I lost track of him (this was before Facebook and cell phones) because he moved away. His mother decided that she wanted better for her son; therefore, she worked hard, saved money and looked to provide her son a better situation. Dr. W. E. B. Du Bois developed an ideology called the “talented tenth”, in which some African Americans to rise, pulling the mass up with them. King disagreed with this philosophy in the 1960’s because, at the time, African Americans had no real way of creating a better life as individuals, let alone as a group (28). Today that is not necessarily the case.

I understand that things can always be better, but in today’s world, there is a path for success. There have been many African Americans that have navigated the ladders of success in politics, sports, entertainment, medicine and business. You may say, “it is easy for a white person to rise up”, and while that is true, it does not mean that a person of color cannot. We will only accomplish what we think we can accomplish. I love to hear about millionaire athletes, who, through hard work and good choices make it out of bad situations, turned their lives around, and give back to their community. There is a need for more people to show the way; to educate and mentor the next generation in the ways of life, including finances and relationships. Over my years of ministry, I have found that people need more than a handout. The old saying, “give a man a fish and you’ll feed him for a day, but teach a man to fish and you’ll feed him for a lifetime” is true. As the “talented tenth” begin to use their influence to not just help, I feel we can and will see a shift in the balance of justice and equity. When people understand that their platform and influence is not for their glory, but to serve others, then we will be on the path toward victory.

Finally, as a friend and I were talking one day, he told me of a church that wants to become more multiracial but just can’t seem to “crack the code”. Curious, I asked him, “Why do African Americans attend our church?” We don’t sing gospel. I don’t preach like T.D. Jakes or Tony Evans, and we don’t do anything to appeal to any one race over another. I believe his responses are simple and effective ways to begin the healing process between the races and start moving toward justice in our nation:

- You don’t try to appease. People know when you are being fake. When we try to be something we are not, we usually come across as offensive.

- You have African American friends. We need to make friends with people of different races, not to put a notch on our belt, but to really expand our circle of relationships.

- You love people. When you set your heart to love and accept people, it become contagious.

- You promote African American people. At our church, we don’t have token African American leaders. We have leaders, and some of them happen to be African American.

I pastor a wonderful little church in Birmingham, Alabama. Our church is a beautiful “gumbo” of colors, classes, and countries. In this current climate of racial tension, it is my heart to have place where people can catch a glimpse of heaven…a glimpse of Dr. King’s dream for America; a place where black and white don’t just attend together, but do life together. We aren’t perfect but we fight for unity, peace and most importantly, love. I believe our nation should be like that gumbo…different flavors and backgrounds coming together to create something wonderful.

Gabriel Wright, along with his wife Perry, started and pastor Gateway Family Church in Birmingham, AL. They have three children.