by W. JAKE NEWSOME, Ph.D.

This month the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum marks its 25th anniversary. This offers a chance to reflect on the mission and work of the Museum, and also an opportunity to look forward at how we will ensure the permanent relevance of Holocaust history for new generations, reach global audiences, and create more agents of change who will work to make the future better than the past. Working with partners like the Institute for Human Rights at the University of Alabama at Birmingham is vital in achieving this mission.

In the fall of 1978, President Jimmy Carter established the President’s Commission on the Holocaust, which was charged with the responsibility to submit a report “with respect to the establishment and maintenance of an appropriate memorial to those who perished in the Holocaust.” One year later, the Commission concluded that the memorial could not be a static monument. Instead, it should be a “living memorial” with a strong educational component. The result was the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, an institution that is both a memorial to Holocaust victims and a museum that educates visitors, collects and preserves evidence, and produces leading research and scholarship. The Commission also issued a call to action, concluding that “A memorial unresponsive to the future would also violate the memory of the past.” As such, in addition to honoring the memory of Holocaust victims, the mission of the Museum is to inspire leaders and citizens worldwide to confront hatred, prevent genocide, and promote human dignity.

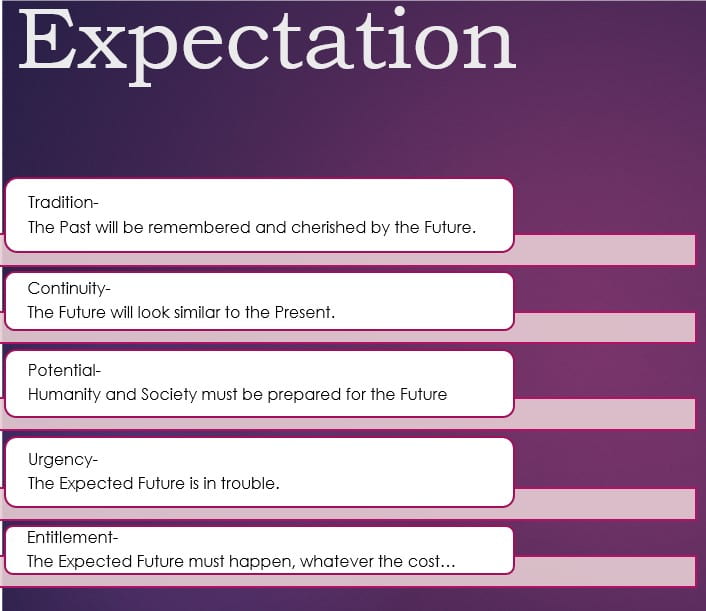

When the Museum was dedicated and opened to the public on April 22, 1993, its founding chairman Elie Wiesel told the crowd, “This Museum is not an answer. It is a question.” For the past 25 years, this is how the institution has approached its work: relentlessly exploring complex questions about history and human nature. We have designed programs and resources that not only ask what the Holocaust was, but delve deep into explorations of how and why it happened. Moreover, we aim to prompt people to recognize the importance of this history’s lessons about humankind and societies, and to take an active role in confronting divisions that threaten social cohesion.

It is a sad reality that in the near future, we will live in a time when there are no more eyewitnesses to the Holocaust alive to share their stories. It is more important than ever, therefore, to teach the next generation of emerging adults about the Holocaust as a way to ensure the lasting memory of the victims. As Wiesel says, “I believe firmly and profoundly that anyone who listens to a Witness becomes a Witness, so those who hear us, those who read us must continue to bear witness for us. Until now, they’re doing it with us. At a certain point in time, they will do it for all of us.”

In that spirit, the Museum works with diverse audiences to demonstrate the importance of honoring the memory and exploring the universal lessons of the Holocaust, even if one doesn’t have a direct connection to the history. These audiences include judges, the military, law enforcement, youth, and faith communities.

As the next generation of thought-leaders and changemakers, college students have been an important audience for the Museum. To date, through a wide range of resources, traveling exhibits, seminars, lectures, conferences, and other programs, the Museum has engaged more than 630,000 college students, faculty, and local community members on 545 college and university campuses in 49 states across the United States.

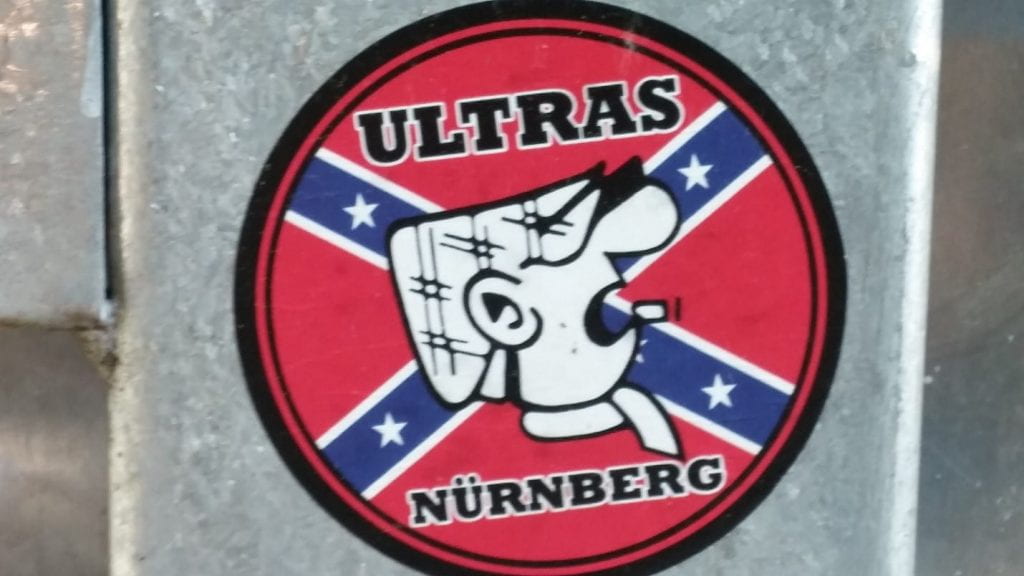

American college students’ interests with the history of the Holocaust are different across the country. Their own background, upbringing, and educational experiences shape how they approach and understand the history of the Holocaust and its relevance to their own lives. As such, the Museum recently launched an initiative to put the history of the Holocaust into conversation with local or regional histories in the United States. This initiative enriches campus dialogue by provoking critical thinking about the history of antisemitism, racism, extrajudicial and state-sanctioned violence, and the power and limits of human agency in different historical contexts. By examining themes through the lens of multiple histories, the Museum connects with new audiences and works with partner campuses to educate students about the history of the Holocaust, model how to responsibly research and talk about different historical contexts, and facilitate informed dialogue about the lessons and contemporary relevance of those histories.

Over the past year, the Museum has been working with faculty and students at universities across the Southeast region on a series of programs that explore the histories of race and society in Nazi Germany and the Jim Crow South. These programs are neither an equation of suffering nor meant to gloss over the uniqueness of each historical period. Instead, they bring communities together to explore what can be learned from studying the similarities, differences, and gray zones of these two histories.

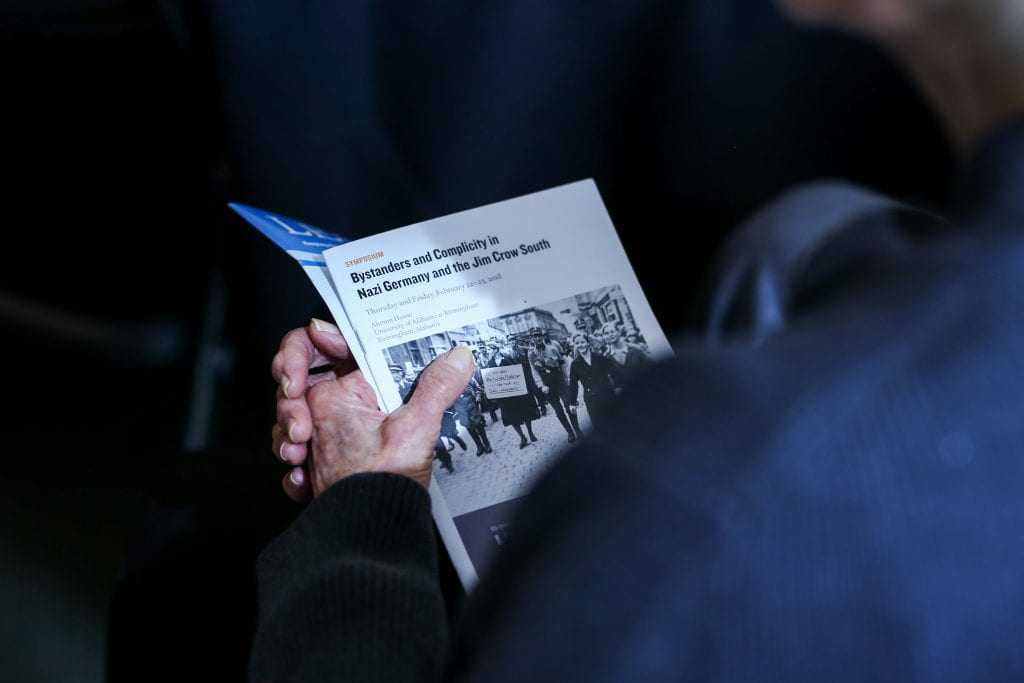

In February 2018, the Museum, with the UAB Institute for Human Rights, organized a capstone event of this regional program: a two-day interdisciplinary symposium entitled Bystanders and Complicity in Nazi Germany and the Jim Crow South. In total, 401 people from 10 states — including 203 college students, 20 high school students, 47 faculty, staff, and teachers, and 131 local community members — gathered together to explore the complexity of these histories.

Through this symposium, history became a way to build common understandings, bring diverse communities together, and foster a sense of human solidarity. Although — or perhaps because — participants came from many different backgrounds, we understood that we were discussing more than just past events. Our conversations posed timeless questions: about relevance to our lives today, about the vulnerability of societies, about democratic values and human nature.

Attendees and presenters discussed how, when, and why ordinary people supported, complied with, ignored, or resisted racist policies in two very different systems of targeted oppression and racial violence. It takes a critical minority of determined leaders with the support of an acquiescent general population to introduce and establish state-sanctioned racism, antisemitism, and violence. The extreme examples of Nazi Germany and the Jim Crow South show that the majority of the population in these two worlds witnessed the widespread persecution against a targeted minority and either actively or passively tolerated what they saw, thus enabling the continuation of persecution and raising pressing questions about the role of onlookers and the nature of complicity. Examining the role of ordinary people, therefore, provides us with a better understanding of how and why such atrocities like the Holocaust could happen. This focus also helps us to make a more intimate connection to the history since we often each think of ourselves as an “ordinary person,” rather than as a victim, perpetrator, or bystander.

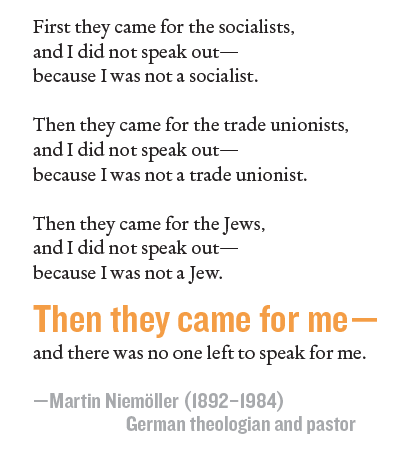

Dr. Beverly Eileen Mitchell, Professor of Historical Theology at Wesley Theological Seminary, delivered the symposium keynote address: “Racism and Antisemitism: Sibling Threats.” She argued that we cannot understand antisemitism and racism as separate prejudices that each affect only one particular group of people. History reveals that while the two may manifest uniquely, racism and antisemitism are children of the same father: white supremacy. “Lessons from history can shed light on what is happening in our own time, if we pay attention,” she says. A key lesson, Prof. Mitchell concluded, is that we all must actively confront discrimination, even when it does not affect us or our community directly, because hate against one group ultimately grows to affect us all. “We must remain vigilant. … There are no innocent bystanders where white supremacy is concerned.”

A highlight of the symposium was “Keeping the Memory Alive,” a session that featured a conversation between Riva Hirsch, a Holocaust survivor, and Josephine Bolling McCall, whose father was lynched in Alabama in 1947. These two women shared their powerful stories about the dangers and personal impact of racial violence and genocide. Their testimony ensured that their memories would be carried on by others. “Don’t ever stop learning about the Holocaust,” Hirsch told the crowd. “Don’t ever stop talking about it. There are people who say that it never happened, but I’m here to tell you all that it happened to me. To you youngsters out there: our memory is in your hands.” But the women also issued a challenge, urging everyone to speak up when they see discrimination. “You can’t wait for someone else to do something,” McCall said. “All it takes is one person to change someone’s mind for the good. Be that one person.”

The women’s parting words reflect a guiding principle of our Museum’s work: when you learn about how and why the Holocaust happened, you now have a moral obligation to act on that knowledge and to confront hatred and promote human dignity.

As we honor the memory of Holocaust victims during the Museum’s 25th anniversary, we recommit our affirmation that the exploration of this dark history must illuminate lessons that can guide us in our mission. One important lesson is that, as individuals in a pluralistic society, we have a responsibility to each other, to defend against threats to social cohesion, and to protect democratic institutions. Second, the confluence of motivations, pressures, fears, and concerns of daily life means that moral choices are not always clear or easy, yet we must commit to making the moral choice. Our (in)actions have unintended consequences and reverberate further than we may realize. What you do matters.

And finally, one of the most important lessons is that the Holocaust was preventable. “That’s not just a statement of fact,” says Museum Director Sara J. Bloomfield. “It is a challenge to all of us.” After the Holocaust, the world promised “Never Again.” But this promise cannot only apply to mass atrocities or genocide. It is up to each of us to make sure that “Never Again” is a challenge to combat discrimination, prejudice, and hatred before it evolves into violence. Never Again begins with you.

Dr. Jake Newsome is the Campus Outreach Program Officer at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, where he is responsible for developing strategic outreach programs and resources for institutions of higher education throughout the United States. These programs take the lessons of the Holocaust beyond the Museum’s walls and inspire new generations of scholars, students, and leaders to engage with the history and contemporary relevance of the Holocaust. Dr. Newsome’s research focuses on Holocaust history, gender and sexuality, and memory studies.