Many who know me from UAB see me as a traveler, who continually explores the Middle East; yet my first experience aboard was in a completely separate region. In 2012, I traveled across the globe for the first time with my school’s Japan Club for a two-week cultural exchange. I was keen on seeing the world. Our school group enjoyed the usual tourist activities but the interactions with my Japanese host family made the largest impact on my perception of other cultures, eventually setting me on my current course. I assumed before embarking on my trip that my host family would be ridged and slightly cold, an imposed stereotype of Asian families. They met me, instead, with overwhelming warmth and kindness as soon as I arrived. This changed my view of Japanese culture, and subsequently challenged the way in which I viewed other cultures. Upon this revelation, I turned my attention to the culture I saw most demonized in the US: the Arab world. Much of the information I received about the Middle East came through a post-9/11 lens. Therefore, I pursued an academic study of the region in college, educating myself about its culture, religion, and language in order to dispel my own personal biases along with the biases held by others who may not have had the opportunity to travel outside of their local sphere.

On multiple occasions, I have studied abroad in the Middle East during my academic career at UAB: Oman, The United Arab Emirates, Jordan, and worked for a summer in Turkey (discussion of its placement, as Middle Eastern or European is further down). There are so many elements of diversity in and between these regions, that it is difficult to compare them all. The most common question I receive when I return is whether I had to cover my hair. It is an understandable question as there are countless news stories about required or banned headscarves or religious swimwear in certain areas of the world. A headscarf covering is also a very visible sign that a woman belongs to the Islamic faith, and generally used as the image representing Islam itself. However, there are nuances to this custom that varies by country, city, and even neighborhood, and I have found that starting the discussion about this complex region with dress gives those unfamiliar with the topic a clear reference point on something they have heard about while reframing their views away from stereotypical beliefs.

My first introduction to the normal dress wear of the Middle East was in Oman, located at the southeastern tip of the Saudi Arabian Peninsula. Out of the countries I have lived in, Oman has been the most conservative when it came to dress. Nearly all the women that our school group interacted with wore abayas, black long sleeve dresses paired with a headscarf, called a hijab. We were not required to wear either of these pieces because we are not Muslim; some of my classmates did don the outfit to blend in more on the street. My daily outfit was a pair of long pants, usually jeans, with a long sleeved blouse and a scarf around my neck. I employed this style for all my subsequent trips to the Middle East, even when it was not required.

The dress code rules were much laxer for foreigners compared to the locals in the United Arab Emirates, home of the cosmopolitan city of Dubai. With an international business presence in the country, most westerners wore anything ranging from business attire to short shorts, and some Arabs adopted this code. For the Emiratis who kept the traditional wear of abayas and headscarves for women, and long white dishdasha robes paired with a keffiyeh, a draping headdress for men, there were still differences from the Omani style. An easy spot was the difference in headwear for the men, as instead of a white draping headdress Omani men preferred to wear either a mussar turban or a kuma multicolored hat. For women, the difference is subtler. Women from both countries may choose to wear an abaya; you can gauge their wealth depending on the abaya’s material and the accessories paired with it. Rose gold watches are commonplace on the wrists of those shopping at Dubai mall, along with patterned silk abayas covering fashionable gowns underneath for at-home wear. Even if tradition dictates a certain dress code for outside the home, the women I saw found ways to make their style pop.

Shifting from the Gulf Peninsula, the Levant region (Jordan, Lebanon, Palestine, etc.) have both cultural and international forces shaping their dress. During my stay in Amman, the capital of Jordan, there was a different stratum of dress code. In the more Western areas of the city, usually stocked with expensive coffee shops and foreigners, I found young male and female Arab students who have adopted the American style and were busy studying away in cafes. The women in this category wore their hair-uncovered majority of the time and frequently interacted with their male peers. I lived in a neighborhood outside of downtown where the dress wear was more of a blend. The men wore t-shirts and jeans, or semi-formal attire in businesses; the women would cover their hair but in such a way that they presented a coordinated look, down to their hairpins.

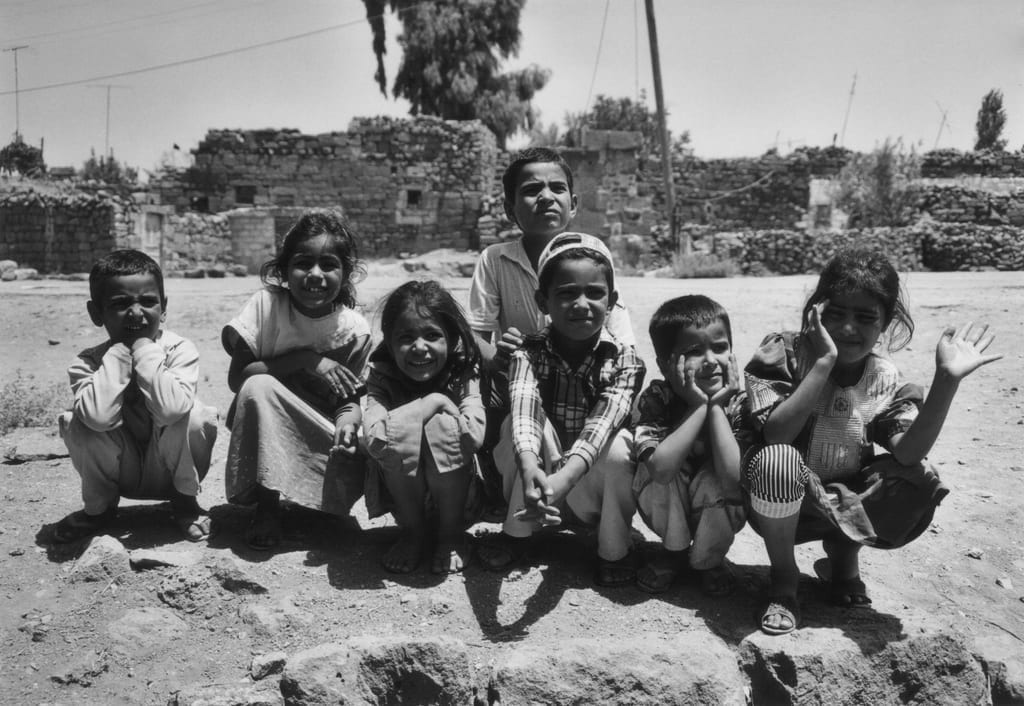

Hijabi fashion is making its mark in the Western world currently; you can see the roots of it on the streets of Amman. On the outskirts of Amman, the dress code becomes more traditional. Here many of the Palestinian and Syrian refugees reside, and these areas are often the poorer parts of Amman. In these neighborhoods, the men also wear t-shirts and jeans but occasionally add a red and white or black and white keffiyeh scarf. The red and white version is popular in Jordan, whereas the black and white version has deeper symbolic ties to Palestine. The women in these areas usually wear abayas, occasionally paired with a niqab, a veil that covers the face but not the eyes. When I travel to these areas, I dress more conservatively, and it is one of the rare occasions where I may cover my hair when I am out on the street.

As a note, in all the countries I have travelled to I have never seen a burqa, a covering where you can see no part of the women. The wearing of Burqas happens in the most conservative areas of the world; yet they are the most recognized covering styles among Americans due to the news coverage on Afghanistan and territories held by ISIS. I have included the names of the different styles as to give replacement terms when discussing Islamic head coverings, and in most cases, the garment worn by those in the US is a hijab.

I have yet to make it to North Africa and compare the average dress code in countries like Egypt and Morocco. The farthest west I have made it in the region is to Turkey. Turkey is an interesting and complex region. Most of Europe considers it an Asian or Middle Eastern country, while Turkey is pushing back to be considered European. It is a bridge between the east and the west and with that comes a substantial blending of traditions and customs. I worked in Izmir, the third largest city in the country and leans more politically liberal. Throughout Turkey, there is a large Muslim population; however, in Izmir, very few people cover their hair, and the city did not enact fasting laws during Ramadan, the holy month of fasting during daylight hours. Living in Izmir was the first time I was able to go to a restaurant and eat outside during Ramadan because there was not a strong adherence to certain strict Islamic principles in the general population. This differs greatly from cities on the eastern border near Syria, certain areas of Istanbul, and even certain neighborhoods within Izmir.

When volunteering with Syrian refugees in Izmir, the dress was much like the refugee areas in Jordan: more conservative with a larger division between the roles of men and women. Some Turks at my work warned me against travel to these refugee neighborhoods as they were known for crime and drugs; the more I went with the volunteer group, the more I found those fears were largely based in a fear of the “other” who spoke Arabic instead of Turkish, and dressed differently. Within the same faith, dress and culture is still a divisive topic. Before my travels, I viewed the Middle East as a single monolithic entity; however, through observing and speaking with those I met from the region, I now see that there is so much more to these countries than I had first assumed.

Dress is one of the many small aspects of a culture. Recognizing the diversity of dress in a region allows us an entry point into the culture as a whole. Actively learning why a group dresses, talks, or acts a certain way, while considering this information from the group’s perspective instead of looking through our own lens, we can come closer to understanding each other as complex human beings instead of 2D stereotypes that lack any kind of depth or nuance.

Through a conversation about something as simple as dress, the complexity of a region can be revealed and open the door for richer discussions about the Middle East. However, I wouldn’t have been able to experience any of these countries without the help of study abroad scholarships offered to students interested in the world outside of the US and Europe. If you would like to study a critical language or do research abroad, UAB has great resources through the Office of National and International Fellowships and Scholarships. They have helped students win awards such as the Critical Language Scholarship, the William Jefferson Clinton Scholarship, the Boren Scholarship, the Rhodes Scholarship, the Fulbright Fellowship, and more. You can contact them with questions and set up an appointment at fellowships@uab.edu.