The Olympics are often heralded as a celebration of international cooperation, but they also reflect the current political and cultural moment in which the games take place. Explained in the book The Games: A Global History of the Olympics, the first modern Olympics in 1896 were only composed of white males, mirroring those who had sole power in society. As the decades passed and the world changed, other races, women, and those with disabilities were added to the Olympic competition roster. This path of progress wasn’t free of setbacks, but the addition of these athletes put out a signal to the world that these groups were to be seen as Olympians; on equal footing as those who had come before. This process of inclusion is still ongoing, and within the past few years a new set of competitors have been given approval to go for gold.

In July 2017, the Olympic Channel launched a new original series, Identify, following the stories of five athletes in the US who identify as transgender, defined as “a person whose gender identity differs from the sex the person had or was identified as having at birth.” Those interviewed ranged in level from a Division III college volleyball player to a professional hockey player, but each of their stories share common threads in terms of their deep passion for their sport and the difficulties of navigating the regulations around being a trans competitor.

The choice to produce the show did not come out of a vacuum. As addressed at the beginning of each video, text appears reading, “In 2016, the International Olympic Committee (IOC) advised that transgender athletes can compete without undergoing surgery, making history in the sports world.” This sentence is referring to a meeting that took place in late 2015 aimed at revising the previous rules on transgender athlete eligibility. Dr. Richard Budgett, Medical Director of the IOC, describes that prior to the new ruling, the IOC policy recommended that in order to compete as a trans man or woman in their desired category the athlete must undergo full lower surgery with internal and external modifications.

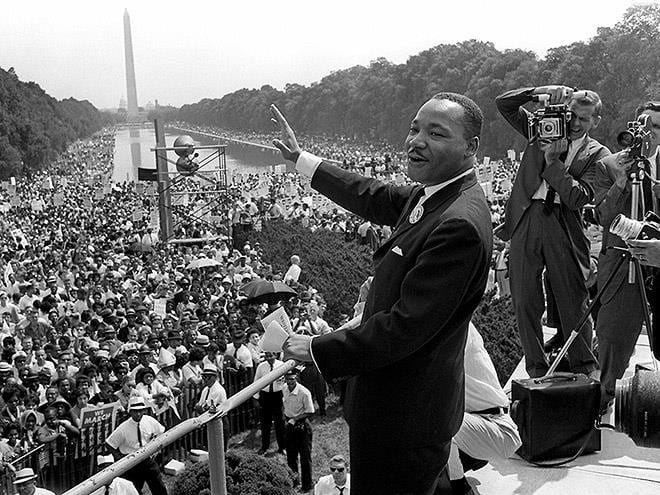

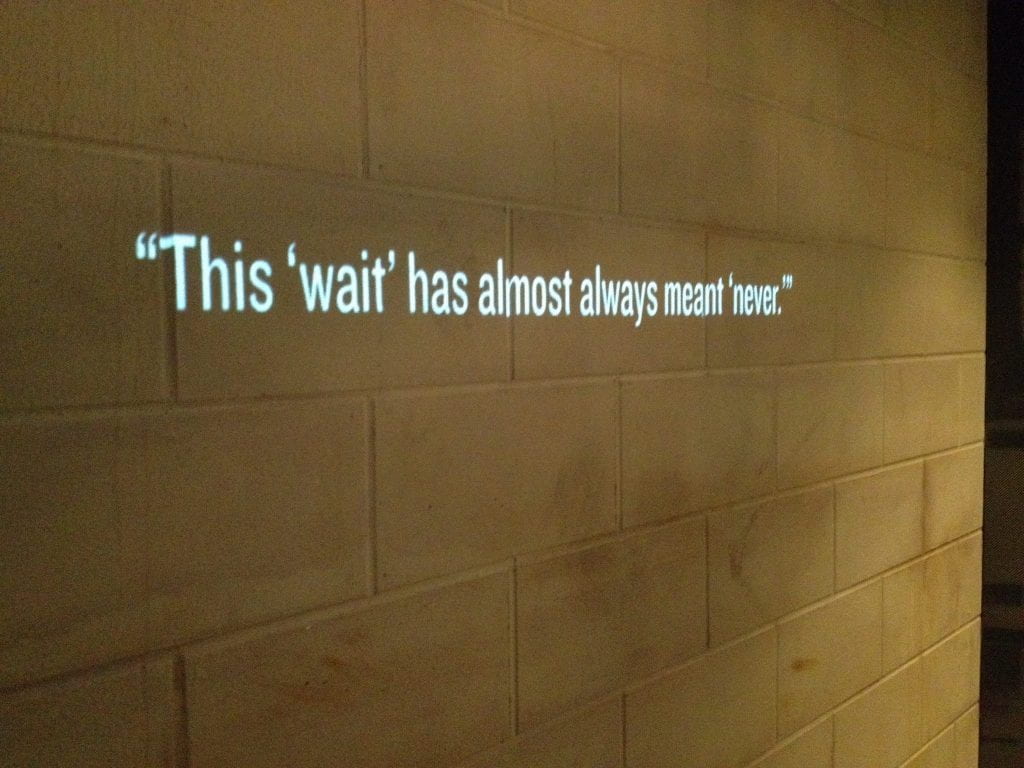

Chris Mosier is the first transgender athlete to compete for Team USA. The old policy did not permit him to race at the Sprint Duathlon World Championship so he decided to challenge the ruling. “My whole thing was that I qualified for Team USA just like the rest of the guys on the team, and I knew that I belonged at the starting line representing our country. What it did was position me as a name and a face to say ‘I’m a real athlete who is not able to compete because you’re asking me to modify my body in a way that I don’t want to.’” Pushed by his advocacy, the International Olympic Committee reconvened with their medical advisors to review the current scientific literature, and from the session drafted the “IOC Consensus Meeting on Sex Reassignment and Hyperandrogenism”.

In the document, there are three categories of athletes covered under the new recommendations. The first category addresses transgender men and states that “Those who transition from female to male are eligible to compete in the male category without restriction.” This allowed Chris to be able to join his team at the world competition, but also opened the door to other athletes profiled in the series, such as Schuyler Bailar.

For his piece in the Identify series, Schuyler begins by recounting how ever since he was little he has been in the pool. “I’ve just always loved being underwater… and it’s always that kind of moment of ‘This is the only thing I’m supposed to be doing right now, this is the only place I need to be.’ That brings me a lot of peace I think that I don’t have in my daily life.”

An injury in high school afforded him the space he needed to process his identity outside of swimming, and soon after he began identifying as transgender. However, he says that “It took me another year until I told most of my friends and asked them to call me male pronouns and refer to me as a boy and solidify the idea of ‘Oh, this has actually always been me, and I’m not actually changing myself, I’m just presenting the truest part of myself.’”

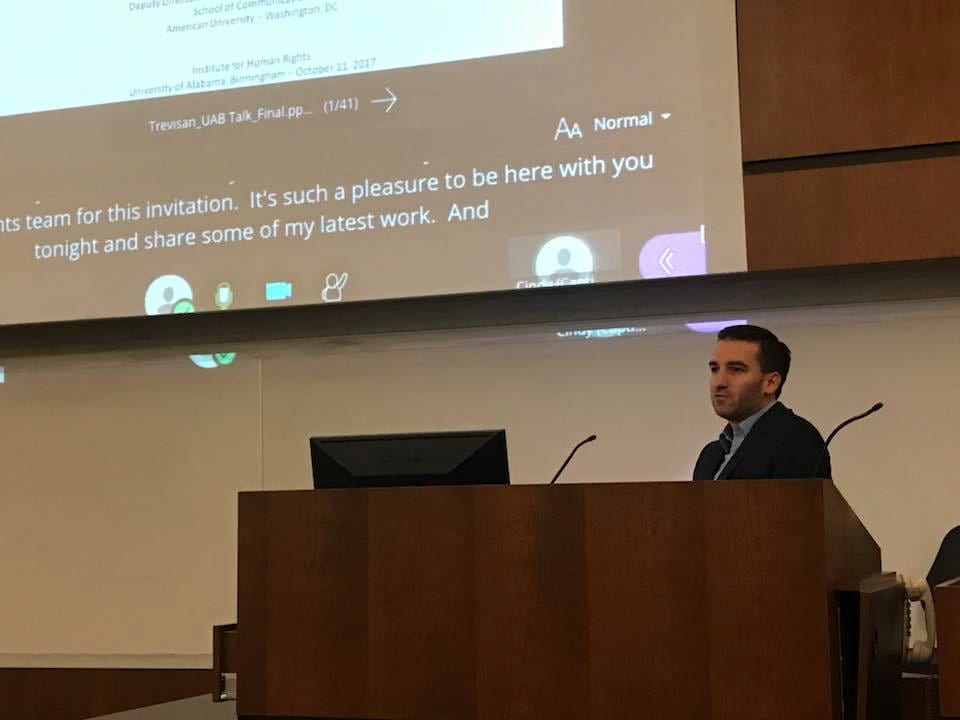

When he’s not at practice for the Men’s Swimming and Diving Team at Harvard, Schuyler can be found speaking in front of audiences about the experiences he has gone through as his public sport’s career and personal identity have intersected. “I love motivational speaking because I’m really invested in sharing my story, and sharing the possibility for this kind of happiness and this kind of peace with yourself, especially with something so complicated as being transgender, but also so simple as just wanting to be happy.” Introduced as the “first openly transgender athlete to compete in any sport on an NCAA Division I team,” Schulyer takes the stage and begins speaking to a crowd of administrators, sharing with them how important a role his teachers and coaches have played in supporting him throughout his life.

As trans men, Chris and Schulyer are both now free to compete for a spot on Team USA just like any other male athlete, without restriction. For trans women however, the rules become more complex. The IOC consensus states that a trans women is allowed to compete in the female category as long as she 1) agrees to make permanent her female gender identity for a minimum of four years, 2) shows that her testosterone level is not above 10 nmol/L at least 12 months prior to her first competition, and 3) submits to testing of these levels.

The focus on testosterone is one which has been hotly debated around the discourse surrounding the inclusion of trans athletes, and it stems from the fear that trans women will have an advantage over other women in competition. The only episode in the Identify series to follow a trans woman featured Chloe Anderson, a Division III volleyball player for the University of California, Santa Cruz. Out of the five episodes posted on Youtube, she has the largest dislike ratio, coming in at just under 50%. One comment sums up the negativity towards her by stating incredulously, “So, basically they allow cheating in the form of men competing versus women but steroids are an ‘unfair advantage’?”

When closely examined however, the general assumptions on what makes a man “better” than a woman in sports, or even how to properly define those categories, becomes much more nuanced and mired in legal battles. Aside from the discussions on whether nationally funded training programs, genetic variations, and economic privileges give some athletes a competitive advantage over others, a recent dispute over testosterone levels in women’s sports shows how difficult it is to pinpoint a single variable for developing a winning athlete.

Dutee Chand is an Indian sprinter with hyperandrogenism, defined by the Gale Encyclopedia of Medicine as an “Excessive secretion of androgens (male sex hormones).” The New York Times reports that Chand was “barred from competing against women in 2014 because her natural levels of testosterone exceeded guidelines for female athletes” by the International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF). This decision to draw a line in the sand as for what constitutes a female athlete caused anger in the sports community, and after the court ruled in Chand’s favor by allowing her to race in the qualifiers for the 2016 Olympics in Rio, the decision-making panel released a statement remarking that “Although athletics events are divided into discrete male and female categories, sex in humans is not simply binary… As it was put during the hearing: ‘Nature is not neat.’ There is no single determinant of sex.”

The IOC specifically addressed this ruling during the consensus meeting, and the discussion around the ruling also sheds light on the reasons the IOC amended its policy on transgender athletes. Trans women are now beholden to the limit of 10 nmol/L of testosterone, within the range of the average female competitor, even though there may be other women who may match or exceed that level. Chloe gives a personal description of what it was like transitioning, disclosing that “Transitioning is like going through puberty backwards, the other direction, twice as far. There’s a noticeable difference in my athleticism… It was pretty challenging at first, just having all my muscle basically melt off my body.” With the legal decision and the current body of evidence, the IOC and the IAAF have both come to the conclusion that opening the female division to trans women who have not undergone surgery still meets the requirements of an equal and level playing field.

While the door has opened wider for transgender athletes to join Team USA, there will be no openly trans athletes competing in PyeongChang this month. However, should you still like to support the LGBTQ+ community at the Winter Olympics, the Human Rights Campaign has made a detailed list of several athletes to cheer for on their website, including skier Gus Kenworthy and figure skater Adam Rippon. Good luck you two!