![Congress of Racial Equality conducts march in memory of Negro youngsters killed in Birmingham bombings, All Souls Church, 16th Street, Wash[ington], D.C. (LOC)](https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/files/2018/02/15336659496_0a3b330baa_o-1024x917.jpg)

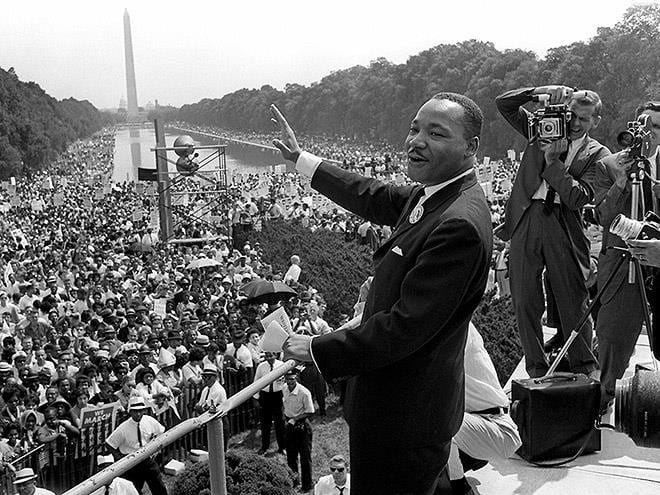

Nonviolence is a demonstration of Black identity. It is an identity, which under the weight of oppression, falls silent while waiting for the proper moment for a revolutionary uprising. Nonviolence is a philosophy that emerges from a personal ethic–an ethic cemented in the tactical decision not to resort to violence. For Mahatma Gandhi during the Salt March and India’s quest for independence from Britain, and Martin Luther King, Jr. during the civil rights movement in 1963 Birmingham, Alabama, in conjunction with Freedom Rides and sit-ins, a nonviolent ethic which spawned movements, revolutionizing the people and nations where they took place. The validation of brute force occurs when police meet with a perceived or actual violent response.

“…Anyone in his right mind knows that this will not happen in the United States. In a violent racial situation, the power structure has the local police, the state troopers, the national guard, and finally the army to call on, all of which are predominately white… Violence as a way of achieving racial justice is both impractical and immoral. It is impractical because it is a descending spiral ending in destruction for all. The old law of an eye for an eye leaves everybody blind. It is immoral because it seeks to humiliate the opponent rather than win his understanding; it seeks to annihilate rather than to convert. Violence is immoral because it thrives on hatred rather than love. It leaves society in a monologue rather than a dialogue. Violence ends by defeating itself. It creates bitterness in the survivors and brutality in the destroyers.”

However, when nonviolence is the position of choice, the revelation of brutality and personification of the law is unjust and excessive.

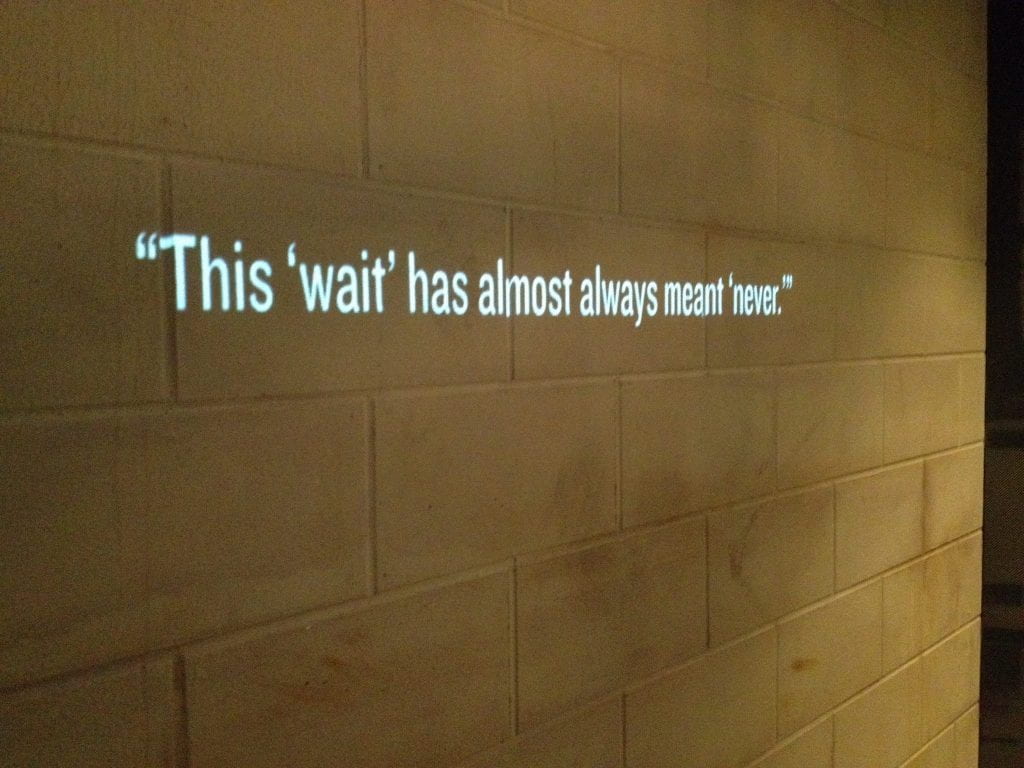

In his book, Why We Can’t Wait, King describes why 1963 proved the perfect timing for nonviolent revolution in pursuit of the freedoms and rights awarded by the Constitution. He points to the Emancipation Proclamation of 1863 guaranteeing Americans of African descent were entitled to receive the same rights as Americans of European descent as citizens of this country. Rights garnered to them as creations of God, who made all men equal, yet the law and the nature of exacting justice on behalf of Blacks continued to fail 100 years later. The struggle of Black Americans under the burden of denial that rendered a deafening and paralyzing silence had finally become too heavy. The process of attaining acknowledgment as an individual and as a race would come only as a means of constructing an unanticipated identity: nonviolent.

Mark Kurlansky claims although there is no exact word defining nonviolence, its existence is evident throughout history:

“Nonviolence is not the same thing as pacifism…. Pacifism is treated almost as a psychological condition. It is a state of mind. Pacifism is passive; but nonviolence is active. Pacifism is harmless and therefore easier to accept than nonviolence, which is dangerous. When Jesus Christ said that a victim should turn the other cheek, he was preaching pacifism. But when he said that an enemy should be won over through the power of love, he was preaching nonviolence. Nonviolence, exactly like violence, is a means of persuasion, a technique for political activism, a recipe for prevailing. It requires a great deal more imagination to devise nonviolent means…while there is often a moral argument for nonviolence, the core of the belief is political: that nonviolence is more effective than violence, that violence does not work” (6).

Many whites, whether European or American, consistently viewed Blacks as inferior. The arrival of Anglo-Saxons and other Europeans on the shores of Africa, island nations, and America speak to the savagery of conquest and the brutality inflicted upon the colonized by the colonizer. To the colonizer, the colonized would become identifiable in terms of animals: savage and barbarian. Classification and ranking based upon physicality and skin tone defined the interactions of the colonized with the colonizer. The terms of existence, foundation, and implementation for the “other” assumed classification.

White superiority is the product of the social construction of race. The “globality”, a term coined by Charles Mills, of white superiority manifests in cultural racism and cultural theft. For du Bois, the overarching reach of white supremacy is fourfold:

- It oppresses. The tentacles of white supremacy affect everything: “history”, interpersonal relationships, politics, justice, and economics—creating systematic and systemic oppression.

- It symbolizes the gain achieved due to the exploitation of nonwhites, more specifically blacks.

- It hinges on false ideals and narratives of black inferiority. The underlying and overarching theme of Black inferiority remains the domestic narrative (in the US). This mischaracterization cultivates a culture wherein Whites exists in an environment perpetuated by rumors, innuendos, accusations, and fear. The replication of this “self-fulfilling prophecy” of black criminality inevitably demands for whites to see Blacks as a criminal at every turn.

- White supremacy consumes every civic and social contribution made by nonwhites, namely blacks, as a method of continually undermining the cultural and social identity, as well as expunge the existence.

In “The Negro Revolution—Why 1963?”, King asserts the Negro Revolution generated quietly as a response of more than “three hundred years of humiliation, abuse and deprivation”. European culture, history, and religion served as qualifiers in the distorted assertion that white and European descendants are civilized while nonwhites are ‘wild’ and ‘savage’; setting the stage for colonization and imperialism as precursors to slavery, racism, and white superiority. Colonizers portrayed the colonized as societies without and impervious to values. “He is, dare we say it, the enemy of values. In other worlds, absolute evil”. The notion of values for the colonized were lost on the colonizers, who customized their abuses and depravity like a trademark. The reduction of Blacks to “zoological terms” dehumanized the colonized; however, the colonized knew they were not animals, and upon the remembrance of their humanity, began to “sharpen their weapons to secure its victory”. Slavery and its dehumanizing conditions shaped the culture of Black resistance and a social identity embracing nonviolence.

Charles Henry (1981) insists changes in values spark revolutions, while Stephen Reicher (2004) argues human social action understood within the context of social interaction, is bound to the parameters of the mind and its processes. Violent revolutionaries like Nat Turner and John Brown dotted the Southern landscape of cotton fields but remain the exception rather than the rule. There is a temptation to classify almost every slave rebellion as violent or aggressive; yet, whether feigning sickness, breaking tools, learning to read in secret, or running away, nonviolent direct action was the weapon of choice for the enslaved person demanding freedom through acknowledgment.

Nonviolent direct action has been a method of resistance for Blacks for centuries, from cotton fields to Harlem and the Great Migration; 1963 was simply the moment when the resistance could no longer remain invisible to the world. For Reicher, the definition of Self is complicated by personal identity as a lone individual and by social identity as a member of a group. To shift from interpersonal behavior to intergroup behavior, an understanding of the seamless nature of the internal “pivot between the individual and the social” is necessary. Social identity requires social context for understanding, and social context has redefined the individual in social terms. Social identity addresses the ideological and structural features of the social world; any attempt to view a portion of whole apart from the whole will distort the perception of both the part and the process.

King questions the reasons for the consistent misery plaguing the Negro and responds “a submerged social group” will create an uprising because they are propelled by justice, lifted with swiftness, moved by determination, and unafraid of risk or scorn. They are a collective; no longer in isolation, aware they are stronger together than apart. He advocates for and presents a meta-analysis framework necessary for understanding individual social identity and behavior in conjunction with identity and behavior of the collective by introducing the concept of behavioral flexibility. Behavioral flexibility becomes identifiable in the cultural changes illuminated by segmentation and categorization through which humanity ascribes meaning, assigns assessment, and determines interaction with another. In short, behavioral flexibility is the basis of culture creation. This creation takes place at both the individual and collective levels.

![[Group of African Americans viewing the bomb-damaged home of Arthur Shores, NAACP attorney, Birmingham, Alabama] (LOC)](https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/files/2018/02/15172976220_6c137e5076_o-1024x682.jpg)

Black leaders employed various perspectives and strategies for dealing with the injustice of racism in America. Each differed from the nonviolent direct action of King. For Booker T. Washington, a leader during the Reconstruction Era and the rise of Jim Crow, Blacks simply needed to remain subservient to the degradation because eventually hard work will help us “pull ourselves up by our bootstraps”. W.E.B du Bois asserted the advancement of a few Blacks, “the talented tenth”, would carry the rest. Separation and journey back to Africa stood firm as the solution for Marcus Garvey, while for Malcolm X, internal separation, through force if necessary, would counter the need for equality with and dependence upon whites. King reminds us that the “elusive path to freedom…for a twice-burdened people” requires the presentation of their bodies–rather than fleeing or cowering under the disappointment—as freedom from the oppressor is “never voluntarily given”, it is demanded.

White supremacy is not only a global and social issue but also a political and personal one. The discourse surrounding white supremacy can no longer remain reduced to exposing racism. It must include the denial of human rights, specifically the deprivation of identity, the poverty of culture, and the theft of ideas. Additionally, the critical notion that white supremacy is a culture of structural and physical violence must become a part of this dialogue. An undoing of structural violence should become the mandate of all races, including whites. Those in power have a responsibility to collaborate with those who are not to dismantle structural violence. The creation of a new global culture is crucial to this process – one including an unwavering commitment to and enshrinement of nonviolent tactics to subvert the hegemony of power in the face of systemic injustice.