On Wednesday, March 31, the Institute for Human Rights at UAB welcomed Dr. Peter Verbeek, Associate Professor in Anthropology and peace behavior scholar, to the Social Justice Café. Dr. Verbeek facilitated a discussion entitled “The Rise in Anti-Asian Violence.”

Dr. Verbeek began by recounting several of the vicious attacks leveled against Asian-Americans in recent weeks. Apparently stemming from the hateful rhetoric and blame-casting around the origins of the pandemic, the nature of the attacks on Asian-Americans listed by Dr. Verbeek included various forms of physical and verbal assault, discrimination, and homicide. After hearing of the horrid assaults that have been perpetrated against Asian-Americans there was an uncomfortable pause in conversation as participants digested the magnitude of the reality and the necessity of standing in solidarity against anti-Asian violence. Looking back to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights’ Preamble, which reads “Whereas recognition of the inherent dignity and of the equal and inalienable rights of all members of the human family is the foundation of freedom, justice and peace in the world,” Dr. Verbeek explained how these attacks constitute a violation of the basic human rights of persons of Asian-descent. He reminded participants that “peace is an ongoing process” and that while pursuing peace, we will constantly face challenges and uncomfortable situations.

Dr. Verbeek then began discussing the mass murder that occurred in Atlanta, Georgia on March 16, 2021. At this point, participants began to share their personal experiences with discrimination and racism. This particular part of the conversation was guided by participants of Asian descent that were extremely candid while sharing their experiences. Many of the stories shared during this segment were heartbreaking and utterly disturbing. One participant expressed how the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated their level of discomfort and fear of being in public spaces. The participant was more afraid of being attacked while being in a grocery store than they were of contracting the deadly COVID-19 virus. The participant also stated they have greatly altered the manner in which they travel in public by wearing heavy clothing, hats, and sunglasses in an attempt to be less noticeable. Hearing the firsthand experiences, fears, and obstacles faced by men and women of Asian descent was a somber but important lesson for all.

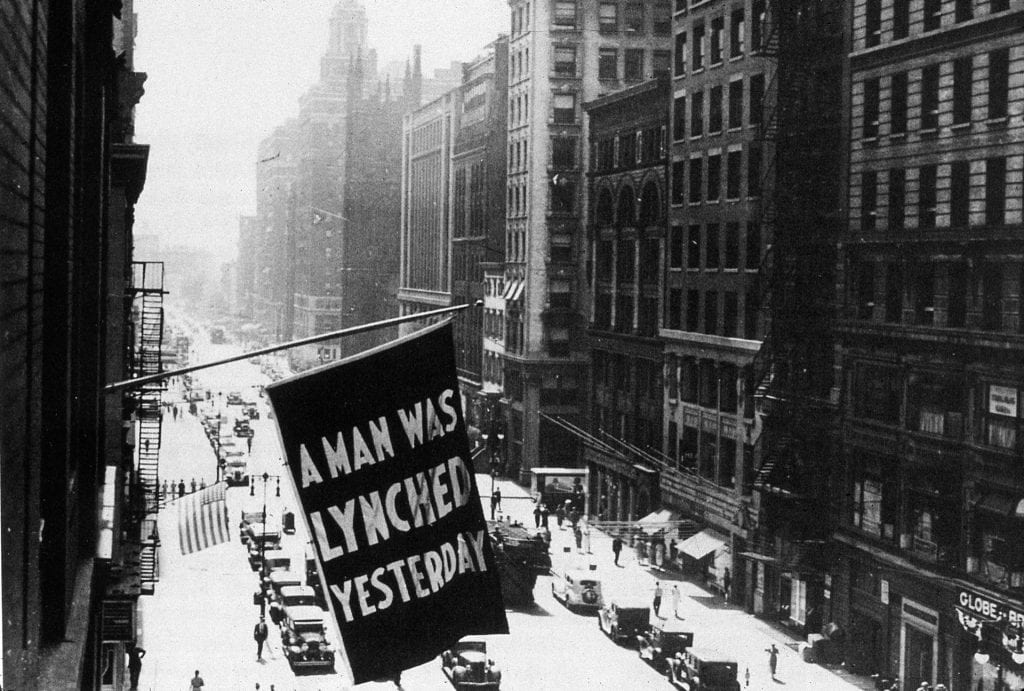

In discussing how to support the Asian-American community during this time, Dr. Verbeek commend the actions of UAB faculty, specifically citing Dr. Kecia M. Thomas’ call for unity and understanding following the mass murder in Atlanta. One participant questioned the power in mass statements calling for unity and how we, as a community, can conceptualize the idea of peace and unity and apply those principles. Dr. Verbeek acknowledged that anti-Asian hate and violence in the United States stems from the December 7, 1941 attack on Pearl Harbor. The hatred and violence experienced by Asian people in the United States is not new and will continue to evolve. Dr. Verbeek found statements of solidarity to be valuable and a necessary tool used to introduce new audiences to the ancient history of white supremacy and oppression of minority communities in the United States.

While discussing mobilization and peaceful activism, a participant asked for advice on how they can better communicate and motivate those in their sphere of influence to become active and speak out against anti-Asian violence and discrimination. The participant’s request for advice was answered by a fellow participant. The advice included the tips to “first be gentle with yourself” then “be gentle with others” meaning, when engaging with others their level of understanding and outrage may not match yours, and this is ok. Be patient and understand that when introducing people to new ideas and concepts the gestation period will vary and to always be gentle with self-criticism. In conclusion, a participant offered a final call to action for all participants to continue to “educate, help organize, and raise awareness” and to continue to advocate for the protection of human rights domestically and globally.

Thank you, Dr. Verbeek and thank you everyone who participated in this eye-opening discussion. The Institute for Human Rights at UAB’s next event, “Pursuing Justice with Love and Power: A conversation with Brittany Packnett Cunningham,” will take place April 6, 2021 at 4:00PM (CT). Please join us and bring a friend!

To see more upcoming events hosted by the Institute for Human Rights at UAB, please visit our events page here.