by Dianna Bai

Disclaimer: This blog post focuses primarily on women and girls who are victims of sexual assault and harassment, though the author acknowledges that both men and women are survivors.

The nation was transfixed on September 27 when Dr. Christine Blasey Ford appeared in front of the Senate Judiciary Committee to testify about her memories of sexual assault, she alleges, at the hands of Supreme Court nominee Judge Brett Kavanaugh when they were both teenagers. Hailed as a “cultural moment” that is couched in the grander chorus of the #MeToo movement, Ford’s quiet, emotional, and powerful testimony serves as a reckoning for women who have suffered in silence for so many years. After Dr. Ford’s testimony, women and men across the country used the hashtag #IBelieveHer to show their support. Two sexual assault survivors confronted Senator Jeff Flake in an elevator on Capitol Hill, possibly the reason why he decided to call for an FBI investigation before the Senate vote on Judge Kavanaugh.

Whether or not Dr. Ford’s testimony changes the Senate vote, she will be a positive example for legions of women who have been afraid to tell their stories. The #MeToo movement is about women taking back their power. As the movement founder Tarana Burke said, “Everyday people…. are living in the aftermath of a trauma that tried, at the very worst, to take away their humanity. This movement at its core is about the restoration of that humanity… They have freed themselves from the burden that holding on to these traumas often creates and stepped into the power of release, the power of empathy and the power of truth.”

Sexual Harassment and Sexual Assault

The prevalence of sexual assault and sexual harassment is staggering in the United States and worldwide.

- Sexual assault is any sexual activity that the victim does not consent to, including rape and sexual coercion. It can happen through force or the threat of force or if the perpetrator gave the victim drugs or alcohol as part of the assault.

- Sexual harassment is unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors, and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature in the workplace or other social situation.

Scores of men in power have recently been exposed for sexual assault and sexual harassment by the #MeToo movement. Sexual assault and sexual harassment are problems that penetrate every level of society and every industry: politics, business, the media, and academia among them. These are only the industries in which women have been most vocal as part of the #MeToo movement. Workers in low wage industries face the most exploitation and are less likely to go public with their stories. According to the National Women’s Law Center, sexual harassment is most severe in low wage industries, including the service industry. In the fast food industry, for example, around 40 percent of women have experienced unwanted sexual behaviors on the job and 42 percent of those women felt that they could voice a complaint for fear of losing their jobs. In the #MeToo era, men in high profile industries have been publicly exposed by the media. In the industries that do not dominate the imaginations of the public, employers are even less likely to take sexual harassment and sexual assault seriously because they do not fear a public relations crisis.

Sexual Assault

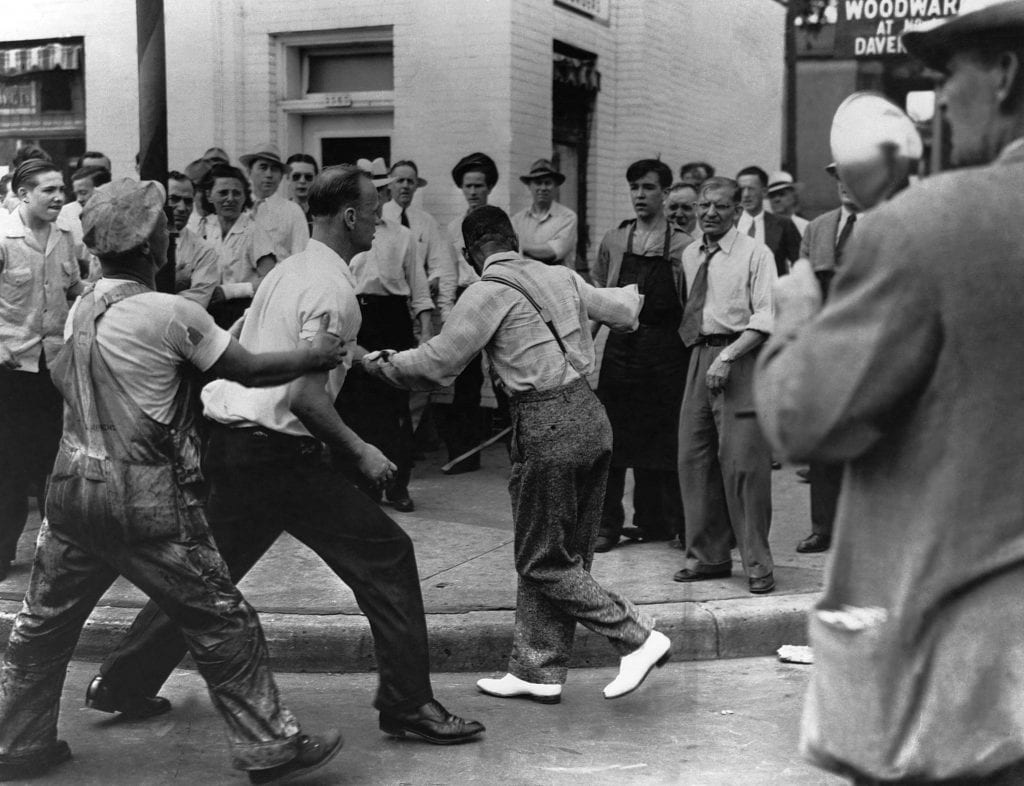

The National Crime Victimizations survey estimates that there were over 320,000 incidents of rape and sexual assault in the United States in 2016. Two-thirds of them will go unreported. It is a social phenomenon according to many scholars. The human rights organization, Stop Violence Against Women, puts it this way, “Social conditions, such as cultural norms, rules, and prevailing attitudes about sex, mold and structure the behavior of the rapists within the context of the broader social system, fostering rape-prone environments…”

Culture is pervasive and omnipresent, creating a powerful influence over the everyday behaviors of people. Gendered norms are ingrained ideas that help define the role of men and women in society and what is acceptable or not. Gender studies scholar Melissa Berger argues that despite being a highly developed country, “American culture and society is imbued with gendered norms relating to domination, over-sexualization, violation, and power and control over women and girls. In fact, violence against women is so pervasive that some scholars have argued that America has a culture of rape, domination, and victimization of women.”

Some of these attitudes include:

- Men are dominant

- Male are entitled to sex

- Manhood is tied to sexual conquest

- The woman’s body is a sexual object

- Women should be pure

Even if a country denounces sexual violence against women on the surface, implicit biases may render such behavior acceptable. These prevailing attitudes, whether implicit or explicit, contribute to the continued oppression of women in American society. A Yale law professor pioneering research on the #MeToo movement emphasizes that sexual assault and harassment are typically manifestations of sexism rather than sexual desire. Some men attempt to prove their manhood or worth by denigrating women.

The controversy over sexual assault has left an indelible mark on college campuses in recent years. From student complaints filed at Columbia University for systematic mishandling of sexual assault allegations to the rape convictions of student athletes at Vanderbilt University, Baylor University and Stanford University in the past five years, universities have had to come to terms with their campus cultures. Twenty to twenty-five percent of college women have been victims of forced sex. A researcher who conducted surveys of college students over two decades found that between 16 to 20 percent of men said they would commit rape if they were certain to get away with it. That number rises to 36 to 44 percent if the question was reworded as “force a woman to have sex.” Many colleges are actively trying to change their culture as it relates to sexual violence, spearheading campus wide campaigns to educate students about sexuality, consent, and intervention.

New laws can affect the culture of sexual assault in a significant way, changing how university administrators respond to sexual assault and encourage or discourage victims from coming forward. Legally, it’s been a delicate balancing act between protecting the rights of victims and the accused. The Obama Administration required the lowest standard of proof, a “preponderance of evidence” in deciding whether a student is responsible for sexual assault. A “preponderance of evidence” means that universities must find the accused to have more than likely committed the crime. The Trump Administration’s Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has enacted new policies that require a higher standard of “clear and convincing evidence,” meaning that it is must be highly probable that the assault occurred. These new guidelines certainly send a signal that there will be less protection for students who report sexual assault. Critics of the Trump Administration argue that the new policy will discourage students from reporting sexual assaults and give universities the opportunity to drastically decrease its attention to sexual assault without retribution from the government or legal systems.

Sexual Harassment

Sexual harassment is not about sex but the abuse of power. The social psychologist Dacher Keltner writes in the Harvard Business Review that feeling powerful can lead to an increase of sexual harassment. “Powerful men, studies show, overestimate the sexual interest of others and erroneously believe that the women around them are more attracted to them than is actually the case. Powerful men also sexualize their work, looking for opportunities for sexual trysts and affairs, and along the way leer inappropriately, stand too close, and touch for too long on a daily basis, thus crossing the lines of decorum — and worse.” Institutions where systems of power are in place are fertile grounds from which abuses of power arise.

The EEOC reported in 2016 that approximately 1 in 4 women have been sexually harassed in the workplace. Think about the implications of that statistic. Everywhere, women (and men) are wearing the invisible scars of abuse whether in the workplace or school. The National Women’s Law Center estimates that 70 to 90 percent of these cases go unreported since victims do not want to derail their careers, cause themselves embarrassment, or believe that nothing will be done. The attitudes of powerful men and victimized women reveal that sexual harassment is clearly very much a cultural problem. We live in a culture that can denigrate the dignity of women at work and in school.

The consequences for women

The most distressing aspect of the widespread, societal problem of sexual assault and sexual harassment is the destructive effects it can have women’s physical and mental health in the long run. Aside from the physical pain and discomfort, victims of sexual assault frequently suffer from post-traumatic stress, depression, suicidal thoughts, and low self esteem, among other consequences. One important aspect of Dr. Ford’s testimony was how she described the impact it had on her life. A trained psychologist, she said the trauma caused by her sexual assault “derailed her life” for four or five years and affected her academic performance in the first two years of university. Decades later, she still needed to talk about the incident in therapy and suggested to her husband that they install a second front door — an escape route — for their home.

For women who have experienced sexual harassment on the job, it often means that their careers will suffer. It can lead to a loss of wages from taking leave for physical or psychological distress and sometimes voluntarily leaving the job for a better environment. One recent study showed that about 80% of women who have been harassed leave their jobs within two years. A recent case from the #MeToo movement, the case of Stanford political science professor Terry Karl, is an example. As an assistant professor at Harvard University in the 1980s, she had been sexually harassed by a senior faculty member who had the power to give her a promotion. Although she filed a formal complaint with the university, it was ultimately she who decided to leave Harvard while he stayed on as faculty and gained increasing renown.

#MeToo Around the World & the Inevitable Backlash

The United Nations estimates that 30 percent of all women worldwide have experienced physical or sexual violence from intimate partners or sexual violence by a non-partner at some point in their lives. The sheer number of women who have experienced sexual harassment across the globe is also astonishing. Here is only a sampling: 57% of women in Bangladesh, 79% of women in India, 99% of women in Egypt (from a survey carried out in seven regions), 40% of women in the U.K. have experienced harassment in public places.

Addressing a problem of global proportions, it’s no wonder the #MeToo movement has spread quickly to other countries. In the United Kingdom, France, Spain, Italy, India, Africa, and the Middle East—creative variations of the #MeToo hashtag have caught on and in some cases caused the downfall of men in power such as British Defense Secretary Michael Fallon.

But the successes of #MeToo have been met with plenty of resistance, even giving birth to the hashtag #GoneTooFar. A Bucknell poll in 2018 revealed that Americans are deeply divided about the impact of the #MeToo movement, with 41 percent believing that it was “just about right” vs. 40 percent believing that it had “gone too far.” Many people believe that the #MeToo movement has gone too far in creating a culture where men are publicly shamed and presumed guilty until proven innocent. It can also create an environment where men are increasingly wary of women and more likely to exclude women from social and mentoring opportunities because they fear the consequences of sexual harassment accusations. We can hear echoes of this sentiment in one of the last lines of Brett Kavanaugh’s opening statement: “I ask you to judge me by the standard that you would want applied to your father, your husband, your brother or your son.”

From state capitols to the technology companies of Silicon Valley, men are becoming reluctant to meet behind closed doors with women and thinking of segregating themselves. The counter narrative was especially poignant in France, where the actress Catherine Deneuve published an open letter with over 100 other notable French women in the arts denouncing the #MeToo movement for infantilizing women and denying their sexual power. They argued that seduction is a sexual freedom and that women could discern between sexual aggression and an awkward pickup. Have we empowered women so much with the #MeToo movement that we are now persecuting men? Who is really the victim here and who should decide the fate of the men accused?

The moment of reckoning for Brett Kavanaugh and #MeToo

The question now becomes whether there has been real change in our culture. The current #MeToo narratives and counter narratives are reflected clearly in the partisan atmosphere that permeates American politics. Twenty-seven years ago, Anita Hill made her allegations about the sexual harassment she endured from then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas in an eerily similar “moment.” In the end, he was confirmed in spite of her testimony. Will Judge Kavanaugh be confirmed for the Supreme Court? Will more women be inspired to speak up after hearing Dr. Ford’s testimony? Will a new generation of young men who have grown up watching the #MeToo movement unfold think differently about their relationship with women. Or will there be a “chilling effect” in offices, schools, and boardrooms across the country as men react defensively? Is this the “cultural moment” that women everywhere have been waiting for?

To learn more: Tarana Burke, founder of the #MeToo movement, will be speaking at UAB on Tuesday, Oct. 9, 2018 at the Alys Stephens Center.

Dianna Bai is a Birmingham-based writer who currently writes for AL.com. Her writing has been featured on Forbes, TechCrunch, and Medium. You can find her portfolio here.