by TONDRA L. LODER-JACKSON, PhD.

Black History Month’s conclusion seems to me an opportune time for reflecting on America’s age-old tension between supporting civil rights versus human rights. As an African American woman educator, I have observed this tension among students, colleagues, community members, and the national media. The paraphrased statements below capture the essence of some of my personal encounters.

“I must admit I was initially resistant to your requirement to attend [the Holocaust-themed film] Paper Clips in a course focused on the Civil Rights Movement.”- A former African American woman graduate student

“I cannot justify investing in international human rights when Black folks in America have so many unresolved problems.” – An African American woman colleague

“I have never heard an African American speak about antisemitism.” – A Jewish woman civic leader’s public comment after an African American woman scholar’s human rights symposium keynote

“Why it Hurts When the World Loves Everyone But Us” – A Black Internet media headline highlighting the outpouring of support for emerging student gun control activists in the aftermath of the February 14, 2018 Parkland, Florida school shooting

These encounters, particularly my own disquiet with the optics of the media’s portrayal of (welcomed) nationwide empathy for school shooting victims and survivors contrasted with (ill-informed) public antipathy of The Movement for Black Lives, prompt me to pose a few questions, and retrace, in hopes of helping African Americans (and others) reclaim, our longstanding tradition of advancing human rights.

A Problem of Scope?

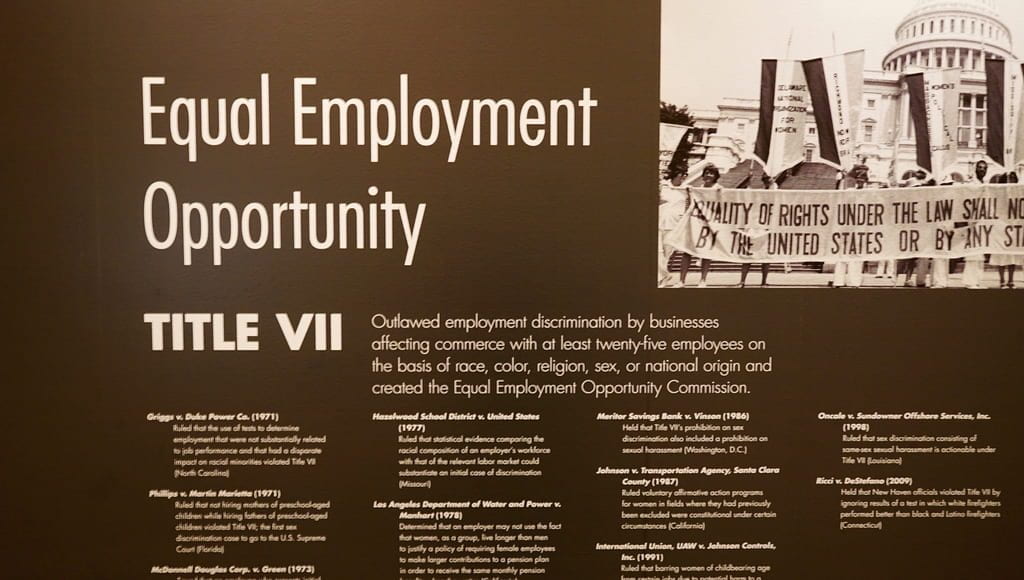

Why so much dissonance about what I consider symbiotic rights? Is a hierarchy of scope culpable? Civil rights – generally defined as an individual’s rights to be treated equally under typically federal law in public arenas such as housing, education, employment, public accommodations, and many more – are quite often viewed as too narrow, too mid-20th century, too Black. In contrast, human rights are defined more expansively as rights “inherent to all human beings, regardless of race, sex, nationality, ethnicity, language, religion, or any other status”. Human rights are generally viewed as being international in scope – that is, focused on human beings beyond, but tacitly excluding human beings within, the continental United States.

Yet, there are key historical moments when Black leaders in the United States strategically elevated America’s civil rights violations to international human rights violations. W. E. B. Du Bois espoused an unwavering belief in the indivisibility of national and international human rights for people of African descent. Likewise, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. used his platform as a civil rights leader to speak out against apartheid in South Africa, global poverty, and the Vietnam War. Four other notables, Malcolm X, Ralph Bunche, Mary McLeod Bethune, and Ida B. Wells-Barnett, also used their platforms as Black leaders to address international human rights. These leaders embodied polarities of diverse Black intellectual thought yet shared the view that advancing Black civil rights constituted a legitimate and worthy human rights agenda, particularly when linked to the destinies of Africans in the Diaspora.

Malcolm X (1925-1965)

After his exile from the Nation of Islam, and on the heels of his transformative pilgrimage to Mecca in April 1964, Malcolm X launched a campaign to persuade African states represented in the United Nations to bring charges against the United States’ oppression of what he then termed Afro-Americans. Malcolm X told friends in New York that he aimed to “internationalize” the Afro-American question at the United Nations in a manner similar to how South African apartheid was elevated as an international problem. The contents of an eight-page memorandum Malcolm X drafted and delivered to African heads of state at a conference in Cairo, Egypt convinced U. S. government officials of his potential for influential global leadership. They surmised that if “Malcolm X succeeded in convincing just one African Government to bring up the charge at the United Nations, the United States Government would be faced with a touchy problem”. Malcolm X suspected that the FBI and CIA demonstrated a particular clandestine interest in his aims for Afro-American advancement once he focused on internationalizing his agenda.

Ralph Bunche (1904-1971)

Ironically, Malcolm X publicly criticized another Black leader, who shared similar human rights aims albeit not means, as a “Black man who didn’t know his history”. Ralph Bunche, whose role as a civil and human rights leader remains woefully overshadowed in American history, was the first African American to win the Nobel Peace Prize in 1950 for brokering the 1949 Armistice Agreements in the Middle East. Known as a consummate diplomat, Bunche helped found the United Nations, soliciting First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt’s support in establishing its treaties. Bunche also supported civil rights causes and was among a group of African American intellectuals W. E. B. Du Bois coined the “Young Turks.” He influenced Dr. King and other civil rights leaders and participated in the 1963 March on Washington and the 1965 Selma to Montgomery Voting Rights March. He also served on the board for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Mary McLeod Bethune (1875-1955)

Mary McLeod Bethune leveraged her accomplishments as the founder of Bethune-Cookman College, a national Colored Women’s Club leader, and a civil rights leader, to become a stateswoman for international human rights. As historian Paula Giddings noted, “Bethune knew how to cajole, praise, apply the right pressure here and there, to move toward a group consensus”. Joining ranks with Bunche and Du Bois as NAACP leaders, Bethune represented the organization at the 1945 founding of the United Nations. In the early 1950s President Harry Truman appointed her to a national defense committee and to serve as an official delegate to a presidential inauguration in Liberia. Bethune and Bunche were among a few Black Americans who had the ear of U. S. Presidents and First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt, enabling them to elevate their causes for African Americans to an international platform.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862-1931)

Bethune once vied successfully against Ida B. Wells-Barnett in 1924 to become president of the National Association of Colored Women (NACW). Both well respected in the Black community, quite similar to Malcolm X and Bunche, they subscribed to different schools of Black political thought. Wells-Barnett was a fiery activist who openly criticized Booker T. Washington’s accommodationist stance on advancing Black progress. Her public attacks were taken none too lightly by NACW leader Mary Church Terrell whom Wells-Barnett once accused of excluding her from the 1899 convention of the NACW. Terrell’s enthusiasm and support for Bethune’s NACW candidacy over Wells-Barnett’s was ill-concealed. Despite these differences, Wells-Barnett joined ranks with Black women and men to expose the atrocities of American lynching to an international audience, drawing national attention and scrutiny. As Giddings noted, “A local antilynching campaign was one thing; an international one was quite another”.

Forging New Human Rights Alliances in the 21st Century

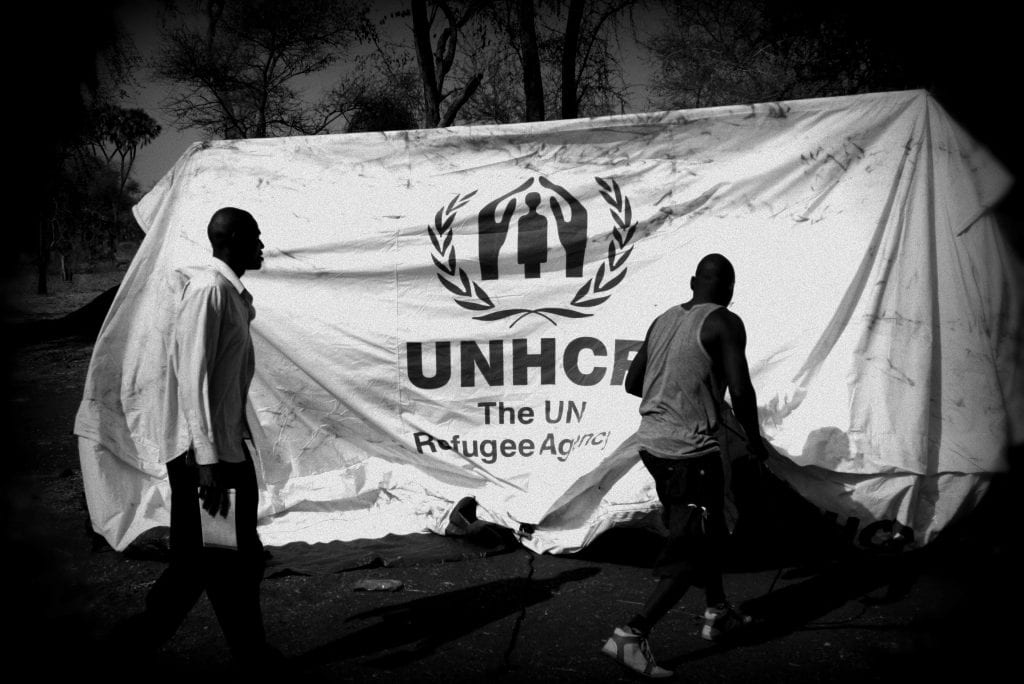

One historical lesson from the experiences of Black human rights leaders is that they forged successful alliances both within and outside of their race to advance civil and human rights. I see hopeful signs of this legacy among younger generations. Notably, twice during this academic year, I have been fortunate to participate in human rights symposia co-sponsored by the U. S. Holocaust Memorial Museum’s Campus Outreach Program, Birmingham higher education institutions, and local Holocaust and civil rights education organizations. These two symposia, hosted at the historically Black Miles College last fall and the University of Alabama at Birmingham (UAB) last week, juxtaposed holocaust experiences in Nazi Germany and the Jim Crow South with meticulous and empathic attention to balancing the unique perspectives and representing the diverse identities of survivors and descendants of these atrocities. The Miles College symposium, according to its organizers the first ever hosted by a Historically Black College and University (HBCU), expectedly drew a predominantly African American audience with a notable number of Whites and other racial/ethnic groups whereas the UAB symposium was fairly racially/ethnically diverse. The symposium brought together a total of 413 attendees, 37 presenters, and moderators from 18 different universities and institutions in 7 states (plus DC), representing 17 different academic disciplines and programs.

I applaud these efforts because they are reminiscent of Black-Jewish alliances in the 19th and 20th centuries that helped advance Black and Jewish representation in American education. For example, the alliance between Birmingham’s Black community and Jewish school leader Samuel Ullman to establish Black schools in slavery’s aftermath. There is also the more familiar alliance between Booker T. Washington and Sears and Roebuck magnate Julius Rosenwald to build thousands of schools for Black children all across the South and extending to the Southwest and Mid-Atlantic states. Rosenwald once proclaimed in a speech: “We like to look down on the Russians because of the way they treat the Jews, and yet we turn around and the way we treat our African-Americans is not much better”. Together, Washington and Rosenwald, with the inestimable support of local Black communities, built nearly 5,000 schools with an estimated $4 million investment from the Rosenwald Project. Finally, there is the alliance between Jewish professors and HBCUs in the 1930s and 1940s highlighted in From Swastikas to Jim Crow. The U.S. South was once a safe haven for a number of Jewish intellectuals who fled Nazi oppression. Many Jewish professors found it difficult to find university jobs in the United States, especially at elite institutions; and even when they did, some were denied tenure for their socialist and religious orientations. Black colleagues at HBCUs were generally sympathetic to their new Jewish colleagues and helped socialize them to the Jim Crow South. The Jewish academics were often astounded by race relations in the South. One professor recounted that when a kind Black colleague gave him a ride home, the apartment manager called him into the office to complain that he had “Negro visitors who were not cleaning ladies or something like that.” A neighbor later warned him that if he did not cease bringing Negroes to the neighborhood that the neighbor would shoot – not at him but at his Black colleague.

History has taught us that forging alliances to address civil and human rights is never easy. These alliances have always been fraught with ideological, racial, cultural, socioeconomic, gender, and countless other differences. There have always been tensions between the aims of mobilizing intra-racial alliances (Malcolm X’s post-Mecca concession that “Whites can help us but they can’t join us.”) versus interracial alliances. Yet no real social movement has occurred without them. Dr. King’s prophetic treatise on human rights penned as a “Letter from a Birmingham Jail” resonates today:

“In a real sense all life is inter-related. All men are caught in an inescapable network of mutuality, tied in a single garment of destiny. Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be, and you can never be what you ought to be until I am what I ought to be.”

Tondra L. Loder-Jackson, PhD is an associate professor at UAB holding a primary appointment in The School of Education and a secondary appointment in The College of Arts and Sciences’ African American Studies Program. She is the author of Schoolhouse Activists: African American Educators and the Long Birmingham Civil Rights Movement.

![Congress of Racial Equality conducts march in memory of Negro youngsters killed in Birmingham bombings, All Souls Church, 16th Street, Wash[ington], D.C. (LOC)](https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/files/2018/02/15336659496_0a3b330baa_o-1024x917.jpg)

![[Group of African Americans viewing the bomb-damaged home of Arthur Shores, NAACP attorney, Birmingham, Alabama] (LOC)](https://sites.uab.edu/humanrights/files/2018/02/15172976220_6c137e5076_o-1024x682.jpg)