Disability is widely defined. Disability is typically thought of an impairment (though this term is quickly falling out of the common lexicon) of the physical, cognitive, intellectual, developmental, or other types of day-to-day functioning in an individual. This convention marked the 10th anniversary of the formal UN codification of the international rights of persons with disabilities, and this year’s programmatic focus was on the inclusion of persons with disabilities in decisions affecting their lives. In other words, persons with disabilities worked side-by-side with UN representatives and other officials to comment on the progress of their rights. UAB’s Institute for Human Rights, in conjunction with American University’s Institute on Disability and Public Policy (IDPP), presented research and policy direction.

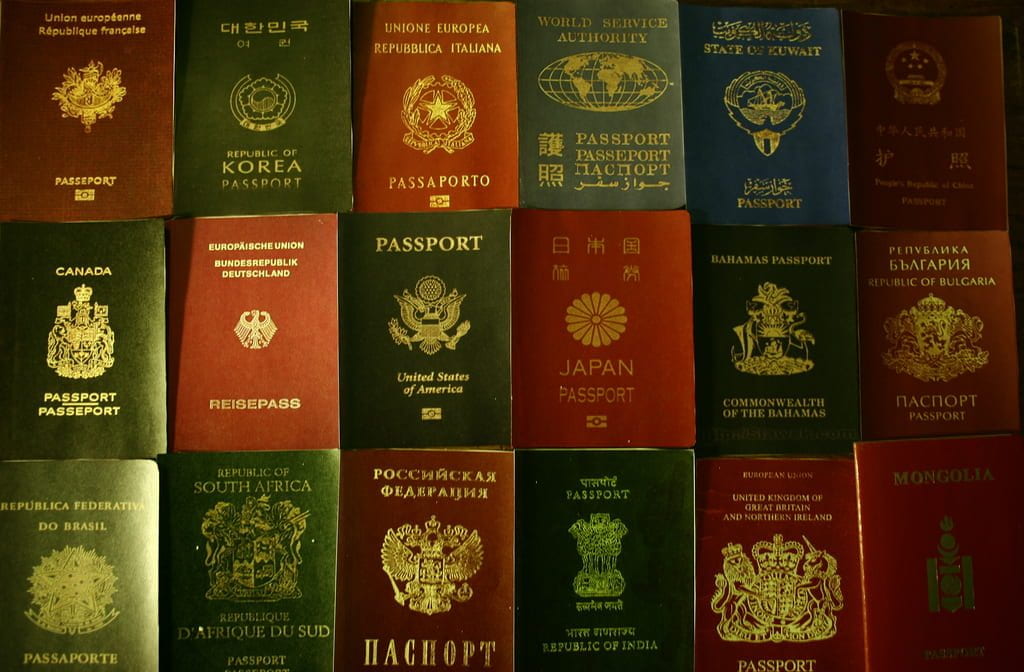

This was my first time to visit the UN. Actually, my first time in New York City. Working with the United Nations has been a dream of mine since I was a young boy. I have dreamed of seeing the member states’ flags waving in front of the tall Manhattan skyscraper, hearing dozens of languages and dialects spoken, and of contributing to the founding principles of human rights and international governance. From inside the UN, the world is a much more complex place than the dream I had as a child. I will elaborate further.

As a rapporteur, I notated the official dialogue between state parties on their progress in implementing the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities. I heard and transcribed over 80 state parties’ efforts to include these persons in the local, regional, national, and international conversation on how to foster a more inclusive world for persons with mental and physical differences. The wording here is intentional because I am choosing not to see persons as ‘disabled’ but with features different from my own; thereby, reframing the perception and honoring their right as a human being first, rather than a disability.

In some cases, the effort was fantastic while others left must to be desired. Australia, in particular, has had tremendous success reaching out to persons with disabilities, especially in aboriginal tribes. NGOs publicly name other states whose efforts are praiseworthy. Public addresses, which are by nature political, served to motivate other ‘lacking’ states to imagine and implement faster, more effective, and more inclusive policies for persons with disabilities. The political game was on full display. Some states simply paid lip service to the CRPD. One state in particular, infamously known for blatant human rights violations bordering on genocide, implored the audience their commitment to human rights and their government’s special attention to persons with disabilities. States with an abhorrent human rights record, upon delivery of their ‘efforts to promote the rights of persons with disabilities’, received cold eye rolls and scoffs from other diplomats. In the official meetings of the State Parties, no love was lost between states who actually adhered to the Convention and states who only signed and ratified for political purposes. The political optics were on full display, and attentive audience members could typically discern authentic investment in the CRPD and inauthentic investment. This political game was in stark contrast to the side events present throughout the convention.

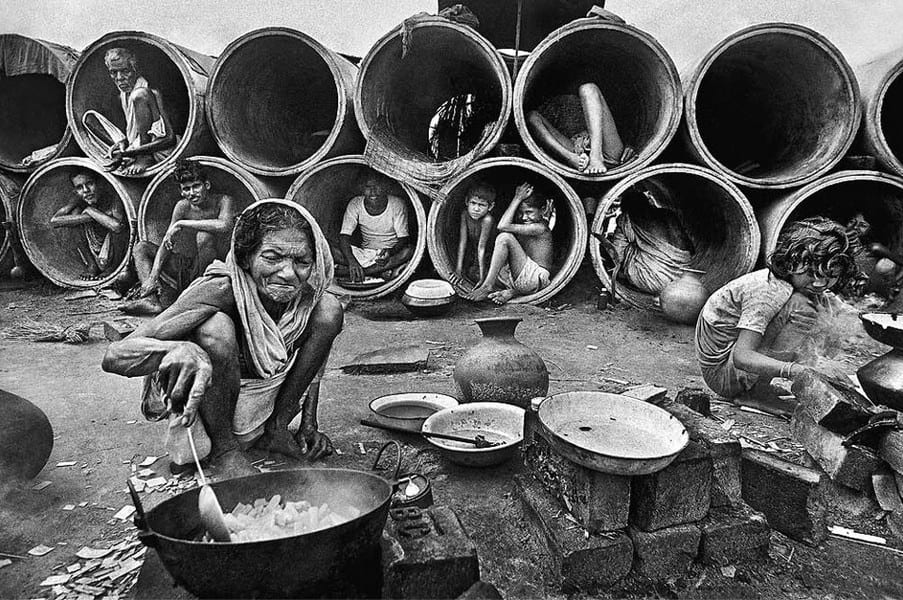

The official State Meetings of the CRPD take place simultaneously with presentations on specific issues to persons with disabilities and solutions created by NGOs, states, and members of civil society. These presentations, similar in execution and functioning to an academic research conference, disarmed the political machine of the UN in favor of real, boots-on-the-ground- efforts to include and empower persons with disabilities from across the globe. Throughout the three days the conference took place, I was awestruck by the tenacity and ingenuity of disabled and non-disabled persons alike in efforts to eradicate the ‘ability barrier’ throughout the world. I heard presentations on cities with universal design (built with accessibility for all persons with disabilities), e-participation in governance by persons previously unable to self-advocate for their rights, research that educates policymakers on the special needs of persons with disabilities, and the general promotion of human rights regardless of ability for all persons. Here, the political spectacle was negligible. These are real persons—with and without physically evident disabilities–working in all corners of the world to ensure “no one is left behind”. Any jadedness from the political spectacle of the official meeting of State Parties dissipates by the passion and ingenuity of all actors displaying their unique methods to ensure universal human rights for persons with disabilities. The breakout sessions were visionary and motivating, empowering and inspirational. The real action is located here, not in the lofty UN assembly meet rooms. The full expression of human rights finds protection and promotion by humans, not by institutions.

Moving forward, as a human rights student and peace advocate, I am still very much interested in a career with the UN. This experience though, assisting in conference presentations and serving as Court Rapporteur for official State Party meetings, left a few indelible impressions on me and changed by outlook and understanding of the UN. Prior to this UN trip, I placed absolute faith the UN system and its machinations. I believed the Conventions (on disabilities, women, children, etc.) enforced human rights. I believed the UN was a human rights ‘police force’ of sorts. I believed international governance was a smooth process and was fruitful in protecting human rights and promoting peace.

Now I understand people, not documents, protect human rights. International governance works when purveyor of rights–people–are vigilant and unrelenting in the protection of their dignity. For those who may not have the opportunity to self-advocate, such as persons with disabilities, we must not put words in their mouths or patronizingly speak for them. They can speak for themselves. We, the able-bodied population, must offer our louder megaphones to them to ensure their voices find expression. The UN works when we, the global community, work with institutions of all levels–local, regional, national, and international–to ensure “no one is left behind” in the pursuit of a world enshrining human dignity and respect. The UN is indeed an ideal but people have the real power. Realistic idealism, in this regard, may be the optimal method to promote and protect human rights. We, the people, owe it to all members of society to remain vigilant, purposeful, and passionate in our advocacy. The tireless self-advocacy of persons with disabilities at the 10th anniversary of the CRPD is a poignant reminder that apathy and indifference has no home in even the most marginalized populations. As a student of human rights and a global citizen at large, this experience changed me for the better.