On November 6, 2018, Florida voted on the Voting Restoration Ballot (also known as Amendment 4) and restored the right to vote of over one million citizens of the state. This is a true success in the improvement of access to voting rights in America. As a country, we have come a long way in terms of civil rights, but the area of voting rights is one that we can still improve.

Voting Rights History

The fight for voting rights in the United States has been in progress for centuries. Ratified on February 3, 1870, the 15th Amendment of the United States Constitution recognizes that the right to vote of all citizens should not be denied based their “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.” This amendment did not make a lot of immediate progress in granting the voting rights of people of color, but it was a step in the right direction.

From the time the 15th Amendment took effect, to the enactment of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, many different measures were used to prevent citizens of color, particularly black citizens, from utilizing their right to vote. One way through which this occurred was literacy tests, which were given to potential voters “at the discretion of the officials in charge of voter registration.” These tests were comprised of questions regarding processes and history of the United States government, and the officials in charge of registration could even decide what questions an individual had to answer. These questions could range from as simple as “Who is the president of the United States?” to ones that most everyday citizens are unlikely to be able to answer, such as one regarding the limits placed on the size of the District of Columbia by the Constitution. The more difficult questions were often intentionally given to potential black voters in order to prevent them from voting. Since the Voting Rights Act of 1965 passed, literacy tests can no longer be used to prevent someone from exercising their right to vote.

What Is the “Voting Restoration Ballot”?

The Voting Restoration Ballot is an amendment that was made to the constitution of Florida through the election on November 6, 2018. The amendment allows for the automatic restoration of the right to vote of citizens who have been convicted of felonies and have served their sentences (excluding those who were convicted of murder or felonies involving sexual offenses). In order to pass it needed to receive support from at least 60% of voters and it actually received support from 64% of voters. The passing of this amendment resulted in the restoration of voting rights for over one million people in Florida and goes into effect January 8, 2019.

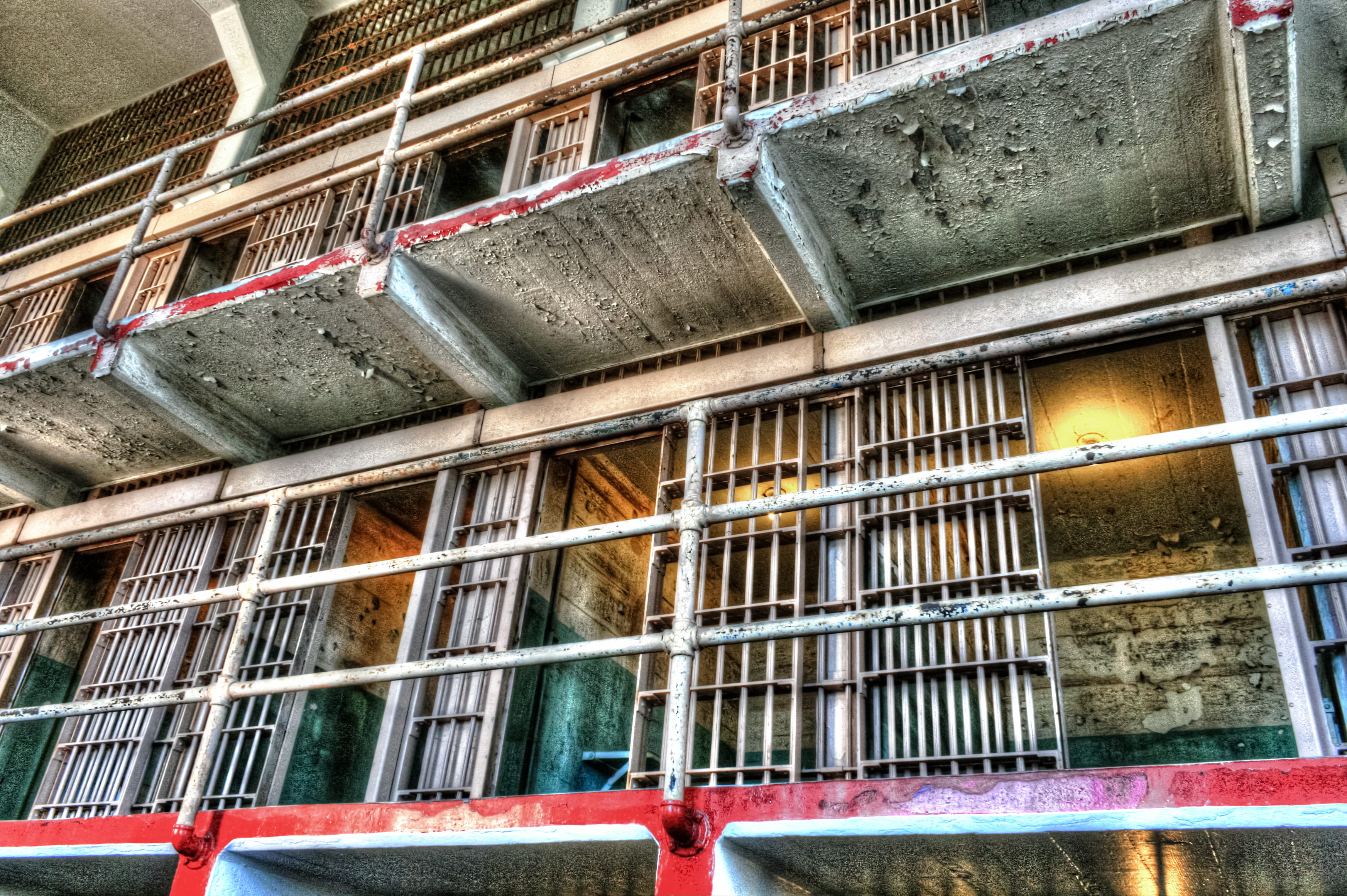

The Issue of Felony Voting Laws

The laws regarding the right to vote for people convicted of felonies vary from state to state. People convicted of felonies never lose their right to vote in Maine or Vermont, even when they are serving their sentence in prison. In addition to Florida, 14 other states and the District of Columbia automatically restore the right to vote immediately after those convicted of felonies have finished serving their sentences, and in 21 states this occurs after a set amount of time following the end of their sentence. In 13 states (including Alabama) there are specific steps that must be taken in order to restore their right to vote, such as a governor’s pardon.

These laws are discriminatory, as they are more likely to have a negative impact on communities of color than white communities. According to the Sentencing Project, potential black voters “are more than four times more likely to lose their voting rights than the rest of the adult population.” This disparity results from the discrimination found in incarceration rates. For example, black people make up 36% of drug arrests and 46% of drug related convictions, even though they only make up 13% of drug users. Evidence suggests that black and white people have nearly the same rate of drug use, but black people are far more likely to be arrested and convicted.

It is also important to note that felonies include a wide range of offenses. In Alabama, they include not only violent crimes, such as assault and battery, murder, and sex related crimes, but also some non-violent offenses, such as drug possession and theft. As a result of this, someone who is convicted of a felony for drug possession in their twenties could potentially never have access to their right to vote again.

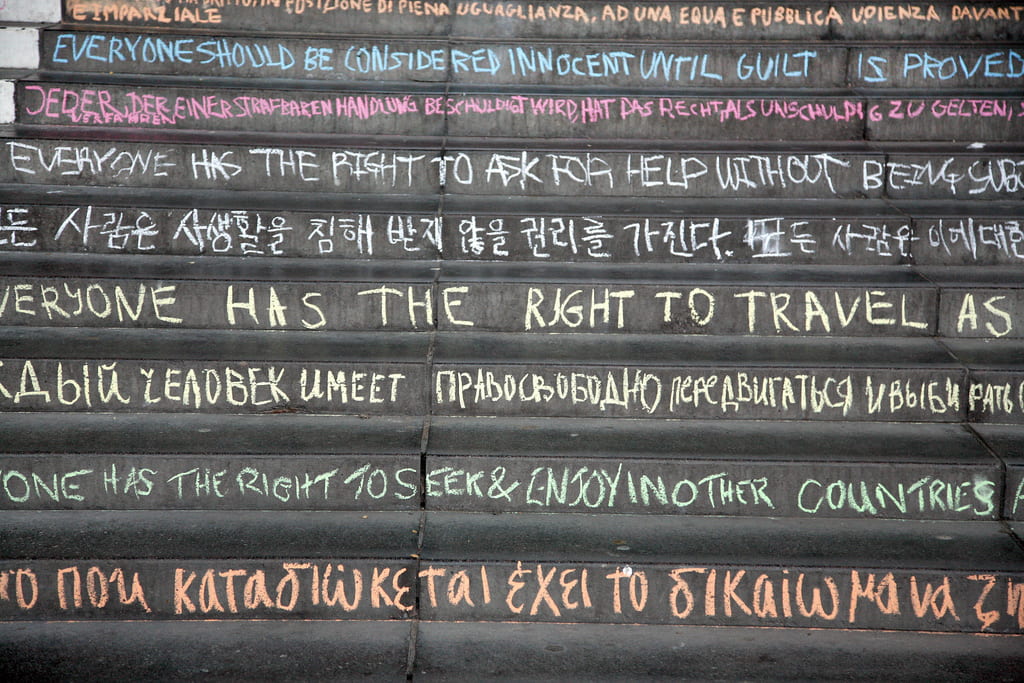

Voting Rights Are Human Rights

The right to vote is more than just a privilege–it is truly a human right. According to Article 21 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, all people have the right to participate in the government they live under, at least through representatives. The article states that “the will of the people shall be the basis of the authority of government” and that this right should be met through elections “by universal and equal suffrage” that should be “held by secret vote or by equivalent free voting procedures.”

Through the passing Voting Restoration Ballot, the people of Florida promote upholding of the rights given in Article 21 and recognize the fact that people convicted of felonies are still human beings who should have access to their human rights.

Another Issue in Voting Rights: Voter ID Laws

In addition to the progress that still needs to be made in restoring the voting rights of people who have been convicted of felonies, the impact of voter ID laws on people’s access to their right to vote also needs to be addressed. There are currently 34 states that either require or request some form of identification to be shown by voters at the polls. There are more than 21 million American who do not possess any form of government-issued photo identification–that is 11% of the population. This prevents many people from being able to exercise their right to vote.

It costs money to get identification issued by the government. There are even costs to getting the documents, such as birth certificates, required to apply for an ID. The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) estimates that “the combined cost of document fees, travel expenses and waiting times” can range from $75 to $175. Many people cannot afford this cost. No one should be deprived of their right to vote based on not having enough money.

Voter ID laws also discriminate against minority groups. For example, black citizens are more likely to be harmed by these laws than white citizens, as 25% of potential black voters lack the qualified forms of identification, compared to 8% of potential white voters. The forms of identification excluded by these laws are also discriminatory. In Texas, for example, concealed weapons permits are accepted, but not student IDs. A study performed by Caltech/MIT even found that there is discrimination in the enforcement of these laws, as voters of minorities are more likely to asked about identification than white voters are.

According to the ACLU, these laws are not remotely necessary. One study found that “there were only 31 credible allegations of voter impersonation” since 2000. ACLU also states that these laws are “a waste of tax-payer dollars” due to the costs of “educating the public, training poll workers, and providing IDs to voters.”

Celebrate the Successes

While it is clear there is still much work to be done in ensuring that everyone has access to their right to vote in the United States, it is important that we take time to celebrate successes in the process and recognize positive impact these successes have on the country. Florida’s passing of Amendment 4 restored the right to vote of over one million people! During the same election, Nevada and Michigan approved automatic voter registration for citizens who are eligible to vote. Michigan and Maryland now allow voters to register on the day of the election. By recognizing and celebrating these successes, we can remind ourselves that progress is possible and that things really can change for the better.