by Pam Zuber

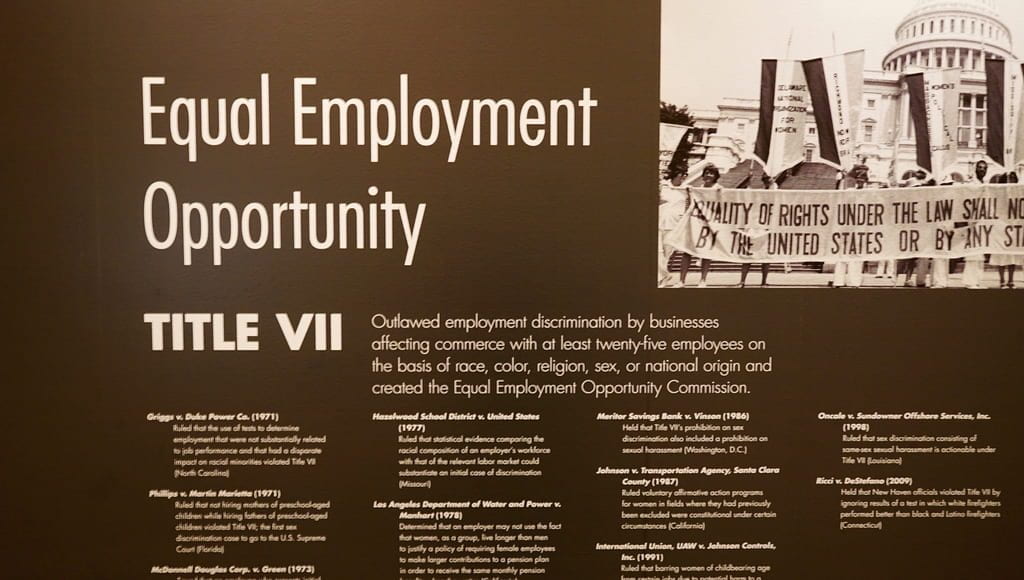

“Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex.”

Twenty-four words that may mean so much. The above words are the text of the proposed Equal Rights Amendment. Long discussed, the U.S. Congress passed the Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) in 1972 but it has stalled since then. Not enough states have ratified this proposal to make it an amendment to the U.S. Constitution. As a basis of comparison, on the international level, the United Nations (UN) sponsors the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). The UN body adopted this convention five years after it was written. Do these differing timelines indicate different perspectives on women’s rights?

What’s the history of the ERA?

The ERA’s journey has indeed been long. Suffragist and feminist Alice Paul, who was instrumental in adding the Nineteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution that gave American women the vote, proposed a version of the ERA as early as 1923:

“Men and women shall have equal rights throughout the United States and every place subject to its jurisdiction.”

Feminists proposed this amendment to the U.S. Congress several times, although it did not pass. In 1943, Paul and her supporters revised the language of this proposal and pitched it to the U.S. Congress several times. Spurred by gains in the civil rights movement and the work of the National Organization for Women (NOW) and other second-wave feminists, the proposal began to garner more support. Such support was from U.S. first ladies, presidents, various politicians, and other prominent people as well as much of the American public. The proposal also generated equally prominent criticism that contributed to its undoing. Conservative activists such as Phyllis Schlafly decried the ERA as unfeminine and threatening to the social order.

After passing the U.S. Congress, thirty-eight states needed to ratify the proposal by 1979 to make it a constitutional amendment. Legislators extended the deadline to 1982, but it didn’t help since only thirty-five states ratified the ERA by that date. Nevada and Illinois ratified the amendment in the 2000s, but Congress would have to pass legislation that extends the deadline to recognize the latest two ratifications. If this deadline is approved and if one more U.S. state approves the deadline, thirty-eight states will have ratified the amendment, although some states have rescinded their previous approval of the ERA. These rescissions make a complicated matter even more complicated.

What could the ERA do?

If the ERA becomes an amendment on the U.S. Constitution, it could mean so much. On a very basic level, the amendment would be a formal, written statement of rights. While the U.S. Declaration of Independence states that all people are created equal and the Constitution makes it illegal to “deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” various authorities have not followed these directives. They capitalized on the vague nature of the language in those documents to create circumventing loopholes or ignored the language entirely.

By addressing the rights of women directly, the ERA is more specific. The U.S. Supreme Court and lower courts could judge individual cases based on this amendment. Legislative bodies could make laws using this amendment as a guide. The ERA could create precedents to follow or to dispute, precedents that would not be subject to the whims of the political considerations of presidential administrations or legislative bodies such as the U.S. Congress or U.S. Senate. Adding the ERA to the Constitution codifies rights for women, especially for women who work in government. It could help define their rights and assist them if they have grievances. It could help them secure better pay to close the wage gap, promote fairer conditions in the workplace, and help women find equality and attain opportunity in general. As a precedent, the ERA could serve as a model for other federal, state, and local laws to grant and protect women’s rights.

What’s the history of the CEDAW and what does it do?

Women’s rights are also a primary interest of the United Nations’ Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW). According to its text, governments that adhere to this convention must “commit themselves to undertake a series of measures to end discrimination against women in all forms, including

- to incorporate the principle of equality of men and women in their legal system, abolish all discriminatory laws and adopt appropriate ones prohibiting discrimination against women;

- to establish tribunals and other public institutions to ensure the effective protection of women against discrimination; and

- to ensure the elimination of all acts of discrimination against women by persons, organizations or enterprises.”

Compared to the long, arduous journey of the ERA, the passage of the CEDAW was considerably quicker and less complicated. Working groups of the UN’s Commission on the Status of Women (CSW) created the text for the CEDAW in 1976. The General Assembly adopted it by a vote of 130 to zero in 1979. After the ratification of twenty member states, it became a convention in 1981. According to the UN, this passage occurred “faster than any previous human rights convention.” One notable country that hasn’t ratified the CEDAW is the United States. U.S. critics of the commission say that such international agreements threaten the sovereignty of the United States. Given the stalled progress of other pro-women initiatives such as the ERA in the country, this failure is disheartening but perhaps not that surprising.

Why isn’t the ERA the law?

While international organizations and governments CEDAW were able to draft, approve, and agree to the conditions of CEDAW (although they haven’t always abided by such conditions), the passage of the ERA continues to stall and generate debate. Why? Some people say that women don’t need the ERA. According to this perspective, U.S. women already have the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and other laws, such as Title IX of the Education Amendments Act of 1972, to protect their civil rights. Others vehemently disagreed that the Fourteenth Amendment covers women’s rights, notably late U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia.

Current laws are inadequate to provide equal rights, say some scholars. Legal scholar and professor Catharine A. MacKinnon observed, “If we’re sexually assaulted if it isn’t within the scope of Title VII as it understands an employment relationship or Title IX in education, we don’t have any equality rights.” The ERA may help provide such rights. Given the current political climate, it is not surprising that the ERA has not passed. In fact, it seems amazing that Nevada and Illinois have ratified the ERA at all. Ideological impasses have prevented other types of political action in recent years. For instance, in 2016, members of the Republican Party refused to host hearings on whether Merrick Garland was suited to serve on the U.S. Supreme Court because Garland was a nominee of President Barack Obama, a member of the Democratic Party. Since the results of 2018 elections meant that the Democrats controlled the U.S. House of Representatives and the U.S. Senate remained in the hands of Republicans, will political deadlocks continue and possibly become even worse? Some people fear that the ERA would expand abortion and create other conditions less favorable to conservative values, so they may be loath to ratify the ERA on a state level or vote in favor of laws that extend the deadline for the ERA on a federal level. They should consider ratifying the ERA and extending its deadline. Measures such as the ERA provide legal protection.

With this legal protection, women would have the security of knowing that they have legal recourse to address any conflicts that arise. Even better, this protection may prevent conflicts from occurring in the first place. No document is perfect. But adding the Equal Rights Amendment to the U.S. Constitution provides rights, opportunities for growth and advancement, and peace of mind. Not bad for a mere twenty-four words.

Pamela Zuber is a writer and an editor who has written about human rights, health and wellness, gender, and business.