Throughout the history of humankind, the way in which people transmit news has evolved exponentially, from the word of mouth in the olden days to a simple click, swipe, and 240 characters. It connects you and I to events happening around the world, from concerts to social movements concerning human rights. But, to what extent does the hashtag, only a recent medium for communication, bring people together around a common goal or movement?

The hashtag originated in 2007 by Chris Messina as a way “to provide extra information about a tweet, like where you are or what event you’re referring to.” Later that October, during the San Diego wildfires, Messina simply created the hashtag “#sandiegofire” and included it with tweets, allowing others to engage with the conversation and gain an awareness of current events.

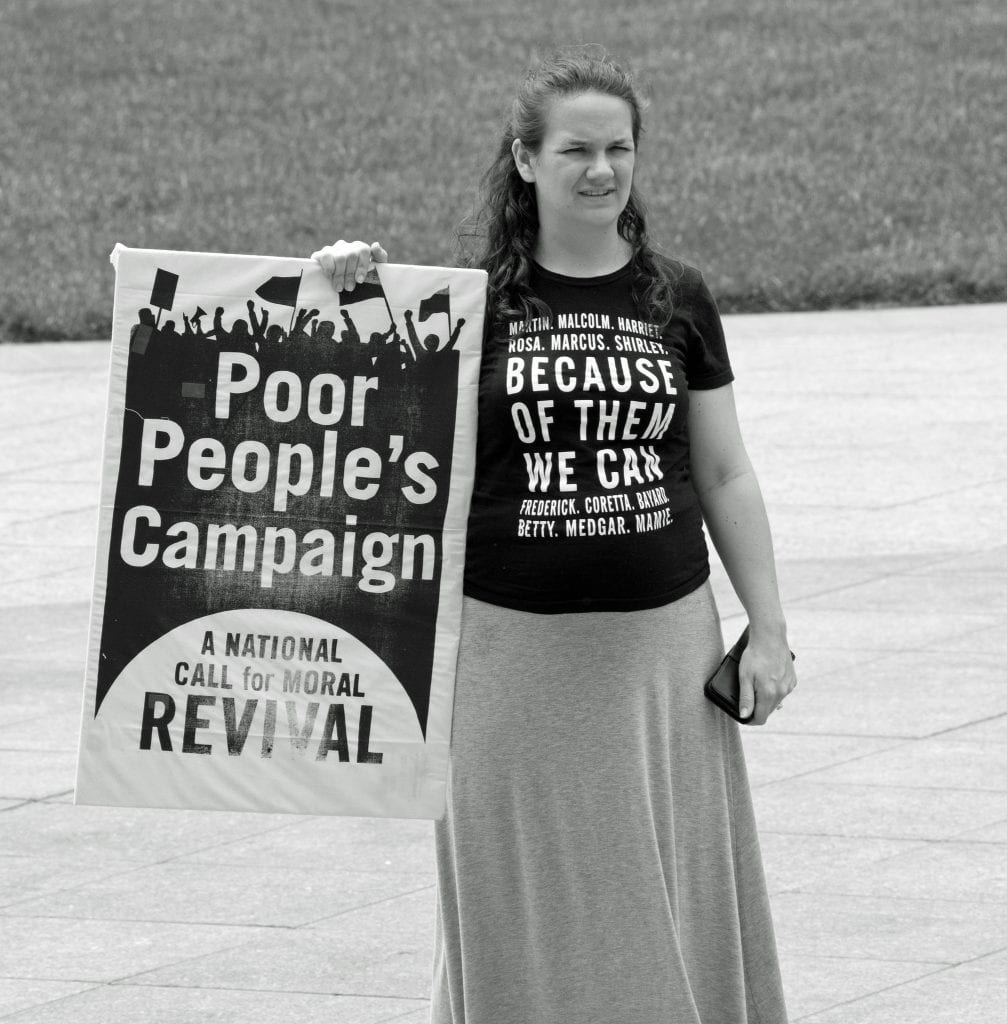

In terms of human rights, the hashtag has also been influential in bringing people together under a common cause, be it international crises, sexual harassment, or even just helping organizations raise money to cure diseases. Hashtag activism, as this is called, “is the act of fighting for or supporting a cause that people are advocating through social media like Facebook, Twitter, Google+ and other networking websites.” It allows people to “like” a post and “share” a post to another friend, thus spreading awareness about the issue at large.

Where and How has the hashtag been influential?

As you might recall in 2014, many people around the world took part in the #ALSIceBucketChallenge, where participants would dump a bucket or a container of ice water on their heads. This challenge went so viral that a “reported one in six” British people took part. It also went so far as involving celebrities like Lady Gaga, which demonstrated its far reach and effectiveness. Despite many calling this challenge a form of slacktivism, (where one would simply like the post and involve very little commitment), the ALS Association raised over $115 million USD. Due to this striking number, the Association was able to fund a scientific breakthrough that discovered a new gene that contributed to the disease.

Then in 2017, the #MeToo movement sprung from the shadows, calling out sexual predators and forcing the removal of many high-profile celebrities, namely Harvey Weinstein. It went way beyond Turkana Burke, the founder of the MeToo movement from more than a decade ago, expected. It was through the use of social media that made #MeToo movement as large as it is today. As of 2018, the hashtag was used “more than 19 million times on Twitter from the date of [Alyssa] Milano’s initial tweet.” This effect, known as the Harvey Weinstein Effect, knocked many of the United States’ ‘top dogs’ from the limelight, revealing what could be behind the facade of power, wealth, and control that they hold. From Weinstein to George H.W. Bush to even U.S. Senate Candidate for Alabama Roy Moore, their reactions varied as much as the amount of people accused. Weinstein was ultimately fired, H.W. Bush apologized for his actions, and Moore denied the accusations. Through increased awareness and the ability to connect to virtually everywhere, women and men began to tell their stories and call attention to the actions of sexual predators.

Both the ALS Ice Bucket Challenge and the MeToo Movement allude to key human rights concerns, with ALS involving the life of a person through a disease and MeToo involving sexual harassment charges and claims. By eliminating the one thing that threatened the life or sanctity of a person (Article 3 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights), a push towards human rights became realized. This demonstrates how hashtags are effective at promoting human rights issues among the general public, allowing these concerns to be confronted and resolved.

But where has the hashtag been limited in practice?

In April 2014, “276 schoolgirls were kidnapped from the remote northeast Nigerian town of Chibok by Boko Haram.” Soon after this event, #BringBackOurGirls shot up to the trending page of Twitter, and was shared more than four millions times, making it one of Africa’s most popular online campaigns. Alongside massive support from the public also came backing from famous individuals such as Kim Kardashian, Michelle Obama, and many others. Even though this campaign helped bring to light the domestic conflict that “claimed at least 20,000 lives,” it only resulted in limited support and is, arguably, an indicator of ‘slacktivism’. With a majority of support coming from Twitter users residing in the United States, Nigerian politics dismissed this outrage as some sort of partisan opposition against the Nigerian president of the time. As Ufuoma Akpojivi (media researcher from South Africa) said, “There is a misconception that embracing social media or using new media technologies will bring about the needed change.” Even with the global outrage at the kidnapping of teenagers, not much action took place because of partisanship and US disconnection with Nigerian citizens.

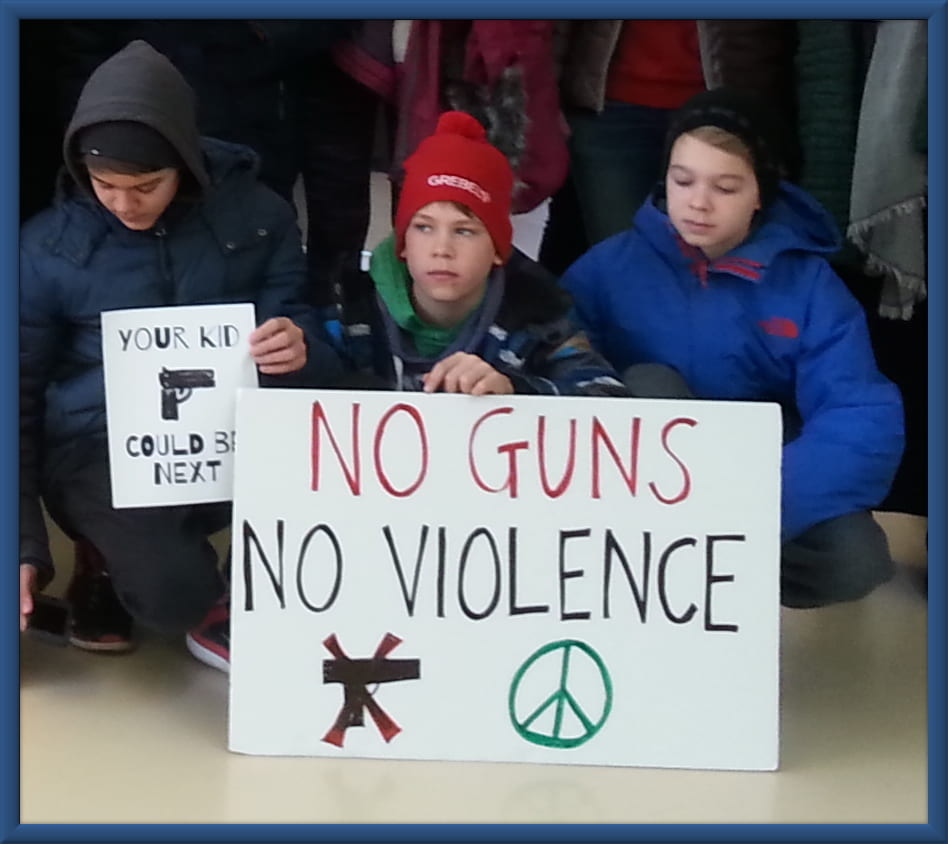

Following, in 2018, hashtags such as #NeverAgain, #MarchForOurLives, and #DouglasStrong emerged as a response to the shooting at Stoneman Douglas High School, where teen personalities and activists Emma Gonzáles, David Hogg, and others began campaigning against the accessibility of guns. Such a movement gained considerable support, with over 3.3 million tweets including the #MarchForOurLives hashtag and over 11.5 million posts related to the March itself. Through the use of social media, the movement was born; however, one of the key things that March For Our Lives disregards is the bureaucratic system that the government embodies. Even though activists want rapid and sweeping changes to the system, Kiran Pandey notes how “there is only the trenchant continuation of political grandstanding, only this time it’s been filtered through the mouths of America’s youth.” Even with such declarations facing our bureaucratic system, alienating people with diverse viewpoints have made the movement weak and ineffective. It does not help when many people, including our friends and family own a gun. By attacking these owners and not focusing on saving lives, this movement has been, and will arguably be, stagnant until bipartisanship is emphasized and utilized.

Though both #BringBackOurGirls and #MarchForOurLives caused widespread protests and promoted awareness about the key issues of the time, it failed to generate support due to its limited field. In #BringBackOurGirls, many of the mentions came from U.S. Twitter users. Because the conflict was and is taking place in Nigeria, many of these tweets and protests have little to no say in the matter of forcing Boko Haram to return the kidnapped Nigerian girls. In the case of #MarchForOurLives, the movement failed to gain traction simply because of its push to call out those in support of having guns and the NRA caused the issue of safety and security of the person to become a partisan issue. Both issues are key human rights issues, however, they fail to capitalize on actual support and exclude those who have diverse views on the issue at hand.

How exactly could someone make a hashtag go viral?

Well, according to ReThink Media, an organization that works to build “the communications capacity of nonprofit think tanks, experts, and advocacy groups,” building a hashtag campaign for social impact includes three key areas to manage a hashtag campaign:

- Having a List of Your Supporters

- Having influencers and connectors can help in a great way. By using a specific hashtag to a broad fanbase or following, having those influencers can help jump-start a movement and gain awareness rapidly about key issues of the time.

- Using the Right Terms at the Right Time

- “Take too long to decide and the news cycle might pass you by.” By using terms that appeal to everyone and using them during critical news-worthy moments, it is easy to be able to attract everyone quickly. For example, if there was some type of crisis going on in the United States, having a relevant hashtag that appeals to everyone could allow more people to support that movement. Using terms that solely appeal to a political side may only be limited in scope.

- Have Supplemental Support Once the Hashtag Gets Posted

- By using certain graphics or memes, combined with the regular posting of the hashtag overtime, during mid-day, more people could potentially get involved and push the movement towards social impact. It also allows people to gain awareness and spread that message to more people in their following.

Overall, hashtags can be effective when incorporating supplemental supporters and a non-partisan central focus. By supporting the movement through influencers and spreading awareness, such a movement could gain traction and provide real-time results, such as the removal of sexual predators from positions of power and gaining funding in order to cure a disease. However, a hashtag’s reliability is solely dependent on the users that spread it. Thus, social media can help people gain a social consciousness and support pivotal human rights issues when they matter most to those affected.